J. Biosci. Public Health. 2026; 2(1)

Under in vitro conditions that destabilize the native state, proteins often undergo structural changes leading to aggregation, implicated in disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. Human Serum Albumin (HSA), a major plasma protein, serves as a model for studying such aggregation-related changes. HSA was incubated at 65°C for 0–256 hours to monitor time-dependent structural alterations. Spectrophotometric analyses, including intrinsic fluorescence, UV and Congo Red absorbance, ThT fluorescence, and CD spectroscopy, were employed. The protective effect with varying concentrations of curcumin (15-60 μM), a known anti-aggregatory agent, was investigated in the presence of curcumin. Thermal treatment of HSA resulted in increased ThT fluorescence at 128 hours and UV absorbance up to 5-fold, indicating protein unfolding and consequently aggregation. Red-shifted CR absorbance of 5 nm and the appearance of non-native β-sheet minima in the CD spectra at 218 nm. In the presence of curcumin, a marked reduction in UV and CR absorbance, along with decreased ThT and intrinsic fluorescence, suggested a partial restoration of native structure. CD analysis confirmed, curcumin mitigated thermally induced secondary structural changes by reappearance of peaks at 208 nm and 222 nm. Thermal incubation of HSA for 128 hours leads to time-dependent unfolding and aggregation, mimicking pathogenic protein aggregation. TEM imaging proves curcumin (45 μM) exhibits a protective effect by inhibiting aggregation and preserving native protein structure, highlighting its potential therapeutic relevance in aggregation-related disorders and as a structural stabilizer in heat-challenged biopharmaceutical systems as well.

Proteins are the molecules, in the nanometer scale, that perform the biological function. They are the building blocks of the cells in biological systems. Protein folding is a remarkably complex physicochemical process in which a polymer of amino acids, in its unfolded state, adopts a well-defined and essentially unique native fold [1]. Protein aggregation is the phenomenon where the protein loses its native structure and adopts a non-native conformation, leading to aggregation [2]. The accumulation of misfolded or aggregated proteins can lead to cell death or dysfunction. Studies on protein aggregation have gained significant momentum in the last two decades due to the discovery of several debilitating human disorders associated with protein aggregation. The protein aggregation disorders may perturb the health of the individual by loss of biological activity and gain of toxicity. There are a number of diseases associated with the formation of protein aggregates, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), etc. These conditions are collectively known as protein conformational disorders.

HSA, a globular monomeric plasma protein composed of 585 amino acid residues with a molecular weight of ~66.5 kDa, has 60% of α-helix secondary structure with subsequent tightening of its structure through intramolecular interactions such as hydrogen bonds [3]. It is the most abundant protein in human blood, constituting about half of the serum proteins produced in the liver. Its concentration range in healthy individuals is normally 3.5–5 g/dl [4]. The structure of HSA is composed of three homologous domains: I, II, and III. Each domain is further divided into two subdomains, A and B. HSA have two drug-binding pockets, Sudlow site-I and Sudlow site-II [5]. Albumin transports hormones, fatty acids, and other compounds and maintains oncotic pressure.

Curcumin, 1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione, also known as diferuloylmethane, is the main natural polyphenol found in turmeric and in other species [6]. It is used in food flavoring agents, food coloring, cosmetics ingredients, and as herbal supplements. Chemically, curcumin is a diarylheptanoid, belonging to the group of curcuminoids, which are natural phenols responsible for turmeric's yellow color. Curcumin is commonly used in Asian countries due to its anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, and antioxidant properties [7]. It is known to alter the aggregation of proteins and reduce the toxicity of the aggregates. Previous studies showed that curcumin inhibits the aggregation of tau protein and α-synuclein [8, 9]. Another study shows that both curcumin and kaempferol inhibit the formation of amyloid-like aggregates [10]. Despite extensive reports on curcumin-mediated inhibition of pathological protein aggregation (e.g., tau, α-synuclein), its ability to stabilize therapeutically relevant albumin against prolonged heat stress has not been sufficiently characterized using time-resolved multi-spectroscopy combined with morphological validation [11].

Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the inhibitory effect of curcumin against HSA aggregates at elevated temperature and enhance structural stability for albumin-based therapeutic applications using thioflavin-T (ThT) fluorescence, Congo-Red (CR) absorbance shift, intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence, Far-UV CD structural recovery, and TEM imaging.

2.1 Chemicals and Reagents

Human serum albumin, curcumin, ThT, and CR were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA), and sodium dihydrogen phosphate and disodium hydrogen phosphate were purchased from SRL (Mumbai, India).

2.2 Sample preparation

The stock solution of HSA (5 mg/ml) was prepared in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer of pH 7.4. The concentration of protein solution was calculated spectrophotometrically by using a molar extinction coefficient of 35700 M⁻¹ cm⁻¹ at 280 nm on a UV-visible spectrophotometer (UV-1900 Shimadzu, Japan). A super stock solution of curcumin was prepared by dissolving it in 100 μl of DMSO to achieve the desired concentration of 100 mM. This 100 mM of curcumin was further diluted to 1 mM by sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4. Appropriate volumes of HSA (50 μM) were incubated at 65°C for 256 hours. Desired concentrations of curcumin (c1-15 μM, c2-30 μM, c3-45 μM, c4-60 μM) were added to the albumin. The samples were checked regularly for the formation of aggregates at different time periods. Similarly, the anti-aggregatory behavior of curcumin was analyzed using various spectroscopic methods like UV-visible spectroscopy, intrinsic fluorescence, ThT, CR, and CD.

2.3 Thioflavin T assay

Fluorescence spectra of native and thermally treated HSA in the absence and presence of varying concentrations of curcumin were recorded with a Shimadzu RF-5301 spectrofluorometer in a 1 cm path length quartz cell. The excitation wavelength was 440 nm, and the emission was 460-600 nm. That was added, and the samples were incubated for 20 minutes in the dark before readings were recorded.

2.4 Intrinsic fluorescence

The intrinsic fluorescence spectra of native and thermally treated HSA in the absence and presence of varying concentrations of curcumin were recorded on a Shimadzu RF-1501 spectrofluorometer (Tokyo, Japan). The excitation wavelength was 280 nm, and the emission was taken in the 300-400 nm range.

2.5 UV Absorbance

UV absorbance spectra of native and thermally treated HSA in the absence and presence of varying concentrations of curcumin samples were taken in the range of 200-400 nm on a UV-visible spectrophotometer (UVvis1900 Shimadzu, Japan).

2.6 Congo Red Assay

The Congo red absorbance spectra of native and thermally treated HSA in the absence and presence of varying concentrations of curcumin were recorded in the range between 400 to 700 nm on a Shimadzu UV-1700 spectrophotometer. The molar ratio of protein to Congo red should be 1:4 [11]. After 10-20 minutes of incubation, absorbance was recorded.

2.7 Circular Dichroism Measurement

Circular dichroism (CD) is measured with a JASCO J810 spectropolarimeter calibrated with ammonium D-10-camphorsulfonate. Cells of path length 0.1 and 1cm are used for scanning between 250-200 and 300-250 nm. The results are expressed as the mean residue ellipticity.

2.8 Image Analysis by Transmission Electron Microscopy

For visualizing the HSA aggregates, TEM was used, and samples were placed on a carbon- coated copper grid and left to adsorb for 1 min, followed by washing with distilled water and drying. Moreover, grids were stained with uranyl acetate for 45 s. All the samples were analyzed by using a JOEL JEM-2100 (Japan) transmission electron microscope operating at 200 kV.

2.9 Statistical Analysis

All the experiments were performed three times independently, and their mean ± SEM values were presented. The significance of the results was determined using a t-test performed in Microsoft Excel 2021. Statistically significant difference was considered at p ≤ 0.05.

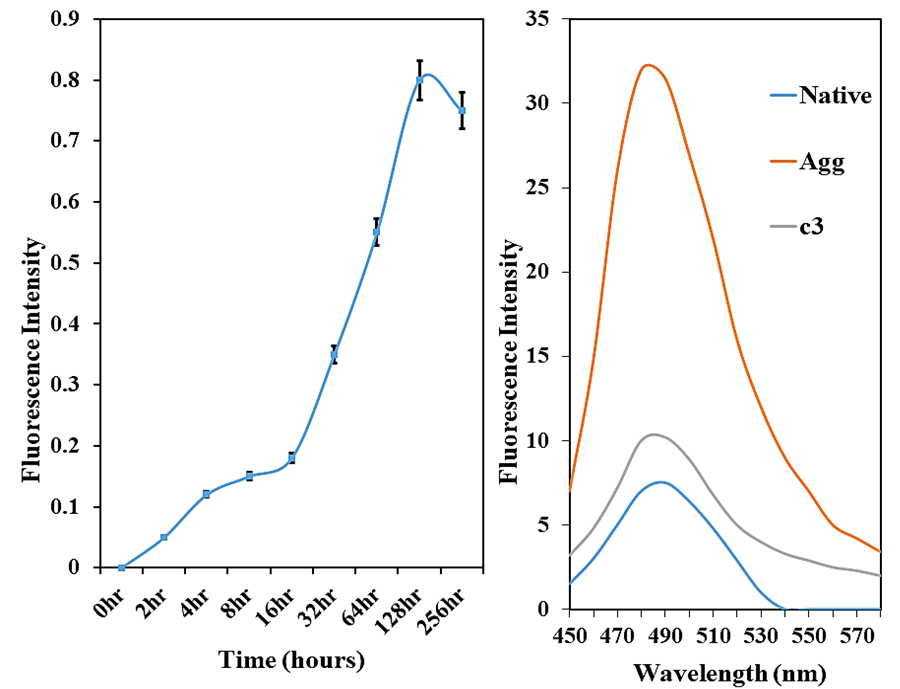

3.1 Thioflavin-T (ThT) Fluorescence Measurements

An increase in fluorescence intensity upon binding of ThT to the aggregates is the most defining and extensively studied property of this dye. The intermolecular β-structure observed in the thermally denatured HSA was further assessed using ThT, a benzothiazole dye that specifically binds to β-sheet aggregates [12]. From Figure 1a, it has been observed that the sample containing native protein showed a reduced amount of ThT fluorescence, which increased several folds in the heat-treated HSA. The simultaneous increase in the ThT fluorescence in the case of the heat-treated protein is possibly due to the abundance of cross β-sheets, which is the prime feature of protein aggregation [13]. Native protein did not bind to the dye, hence exhibiting very low fluorescence intensity, indicating that the native conformation gets altered, ensuring the formation of aggregate structure. When samples were incubated with curcumin (45 µM) to assess the protective action of the antioxidant, there was a significant decrease in fluorescence intensity, which can be attributed to the fact that curcumin inhibits structural unfolding of the native protein, reverting the aggregate formation (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. ThT fluorescence emission spectra of HSA incubated at 65°C for 256 hours (a) and in the absence and presence of curcumin; c3-45 μM at 65°C for 128 hours (b).

3.2 Intrinsic Fluorescence Measurements

Intrinsic fluorescence measurement is a useful technique to identify the native and non-native protein conformations. Intrinsic fluorescence of proteins is specifically due to the aromatic amino acid residues, with tryptophan having the highest fluorescence [14]. Intrinsic fluorescence measurements were measured for the native and thermally treated HSA in the absence and presence of varying concentrations of curcumin (Figure 2). Native HSA at 0 hours showed minimum intrinsic fluorescence intensity, suggesting that tryptophan residues are buried and located in a moderately hydrophilic environment, retaining the native structure. HSA, when incubated for different times increasing from 0 to 256 hours at 65°C, showed a sharp increase in the intrinsic fluorescence intensity with fluorescence maxima at 128 hours. The increase in fluorescence may be due to the structural unfolding in the transition region, increasing the distance between protein and tryptophan, which was initially completely quenched owing to resonance energy transfer to the adjacent groups. This hike in fluorescence intensity is attributed to the exposure of tryptophan residues present in the protein interior on unfolding of the native structure of the protein. Beyond this, at 256 hours, there is a decline in tryptophan fluorescence, which may be due to the formation of ordered and compact aggregates resulting in the burial of tryptophan residues; hence, quenched tryptophan fluorescence is observed. We can say that HSA on incubation for 128 hours at 65°C transforms from a native to an unfolded state and later to an aggregated state because of unfolding and structural loss in protein. As the curcumin was added to the HSA solution and then incubated at 65°C for 128 hours, the fluorescence intensity decreased with increasing concentration of curcumin, indicating that the polyphenol inhibits the structural transformations in HSA.

Figure 2. Intrinsic fluorescence of HSA in the absence and presence of different concentrations of curcumin (c1-15 μM, c2-30 μM, c3-45 μM, c4-60 μM) at 65˚C for 128 hours.

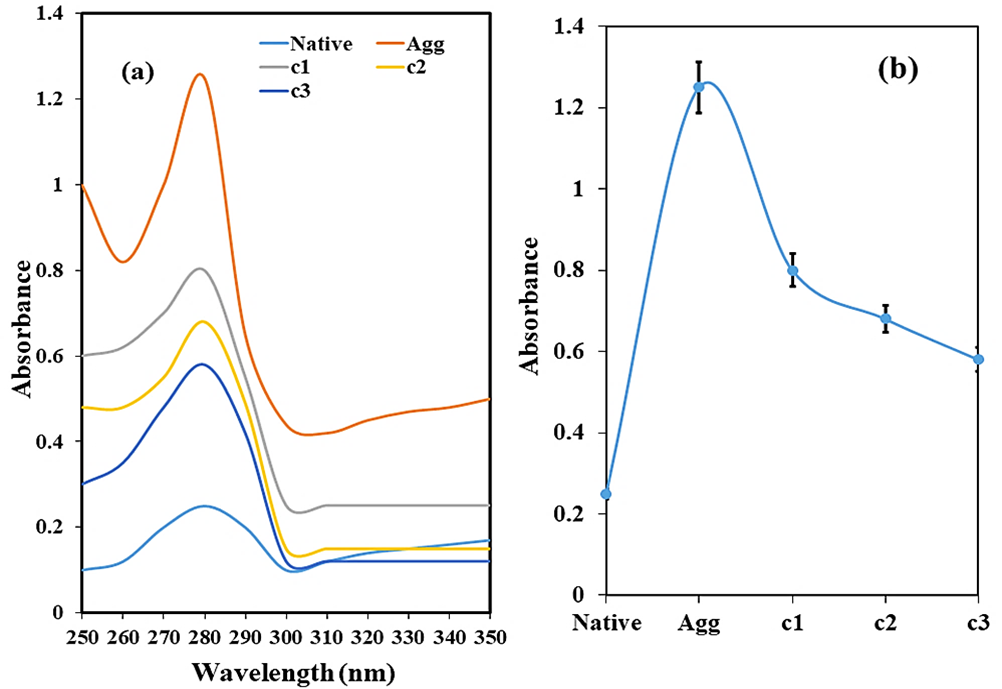

3.3 UV Absorbance Measurements

The UV absorption spectra of HSA after thermal incubation in the absence and presence of curcumin (c1-15 μM, c2-30 μM, and c3-45 μM) were analyzed from wavelengths 250-350 nm (Figure 3a). Native HSA showed minimum absorbance, suggesting that the protein is in its native form. The thermally treated HSA incubated for 128 hours at 65°C has a substantial increase (5-fold) in the absorbance (Figure 3b), most likely due to the formation of aggregates as a result of exposure of aromatic amino acids at elevated temperature. Samples treated with curcumin to assess its potential of inhibiting aggregate formation showed a marked decrease in the absorbance. With increasing concentration of curcumin (15-45 µM), the absorbance decreases (2-fold), notably approaching towards native at 45 µM curcumin. It can be suggested that at 45 µM, curcumin inhibits the unfolding of the HSA at elevated temperature, thereby decreasing its aggregation.

Figure 3. Ultraviolet absorption spectra (a) and relative plot at 280 nm (b) of HSA in the absence and presence of different concentrations of curcumin (c1-15 μM, c2-30 μM, and c3-45 μM) at 65°C for 128 hours.

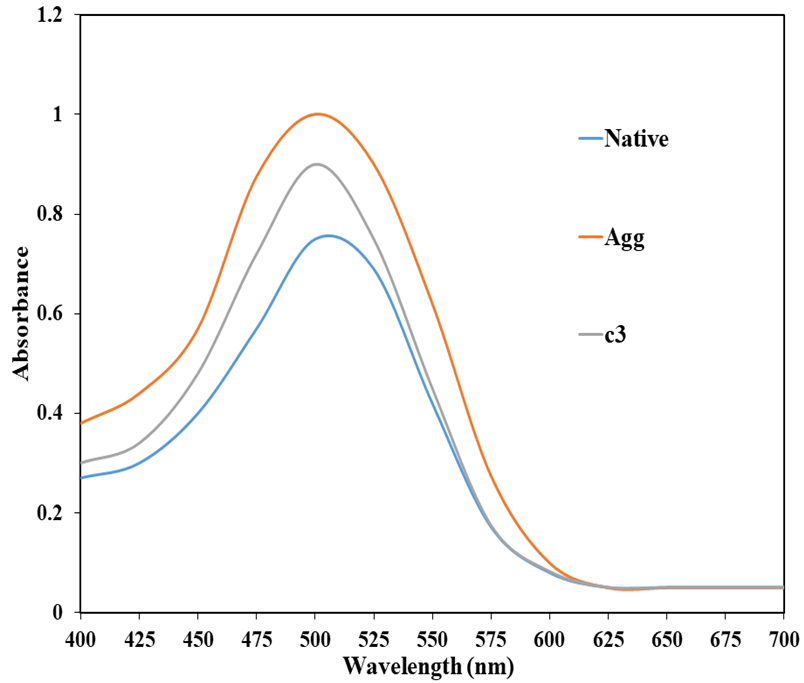

3.4 Congo Red Assay

A Congo red binding assay was performed to authenticate the formation of β-sheets, which is the prominent protein conformation during protein aggregates. Native HSA showed absorbance maxima at around 490 nm, but the heat-treated HSA shows enhanced absorbance with a red shift of 5 nm (Figure 4). The red shift in the CR absorbance is the characteristic feature of aggregate formation in the proteins [15]. When the aggregated sample was incubated with curcumin, the absorbance decreased notably. These results are consistent with the data obtained from the ThT assay.

Figure 4. Congo red absorption spectra of native HSA and HSA in the absence and presence of curcumin; c3- 45 μM at 65°C for 128 hours.

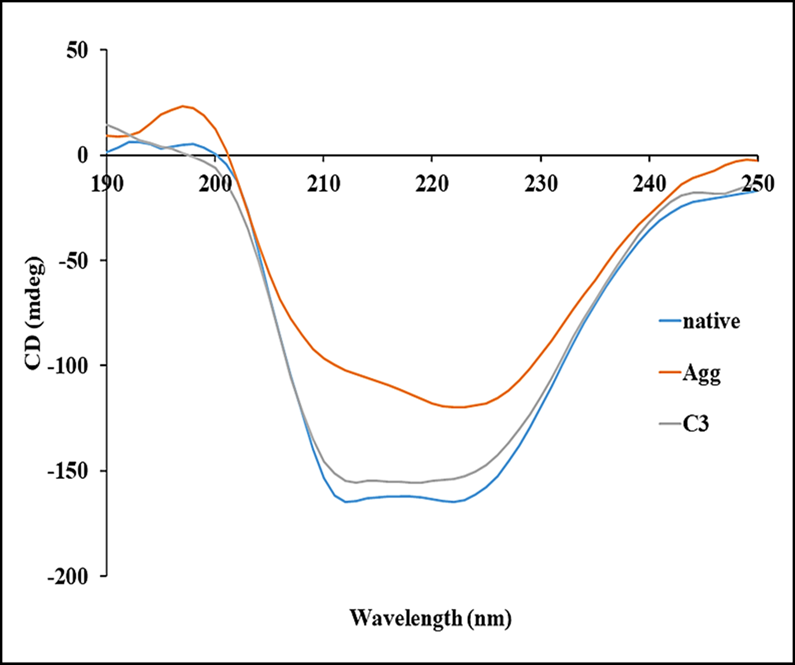

3.5 Far-UV Circular Dichroism

Secondary structural variations in proteins are analyzed by far-UV CD, especially the transition from α-helix to β-sheet conformation, which is an important component of protein aggregation [16]. Native HSA has two negative peaks at around 208 nm and 222 nm respectively (Figure 5), which is the characteristic feature of abundance of α-helix in the native protein [17]. However, in the heat-treated samples, there is a significant loss of helical content from 68% in native to around 32 %. These results show that there is a gradual decrease in the α-helical content of the HSA and increase in the intermolecular β-sheet content when a protein is subjected to high temperature [18]. When HSA was treated with curcumin (45 µM) after thermal incubation, the helical content increases to 58% in the samples.

Figure 5. Far-UV CD spectra of native HSA and HSA in the absence and presence of curcumin; c3-45 μM at 65°C for 128 hours.

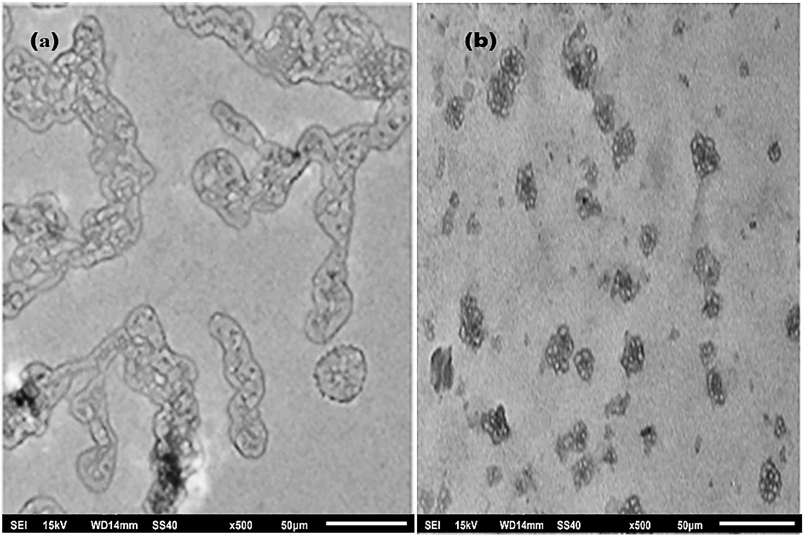

3.6 Structural Transformation Study by Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

To visually authenticate heat-induced HSA aggregates quantified by ThT fluorescence, TEM analysis was performed (Figure 6). The thermally aggregated HSA confirmed the structural transformation of the native protein and formation of oligomeric species (Figure 6a). The sample of HSA pretreated with 45 µM curcumin (Figure 6b) showed lesser aggregates, establishing that curcumin considerably diminished the denaturation and ultimately aggregation of protein. The decrease in aggregate formation is relative to aggregated HSA, showing the protective effect of curcumin.

Figure 6. Transmission electron microscopy image of thermally aggregated HSA (a), and in the presence of 45 μM curcumin (b).

Understanding non-native protein aggregation is critical not only for a number of amyloidosis disorders but also for the development of effective and safe biopharmaceuticals. In the past two decades, the amyloid fibril class of non-native aggregates has been most extensively studied because of their high degree of order and their relevance to human disease. Spectroscopic techniques, such as intrinsic fluorescence, UV absorbance, dye binding methods, ATR-FTIR, far and near UV, and CD spectroscopy, can be used to monitor changes in protein secondary and tertiary structure [19]. Moreover, these aggregated bodies may lead to inappropriate interactions with cellular components such as small metabolites, membranes, proteins, or other macromolecules. All these conditions trigger the abnormal function of cellular machinery, like interaction with cellular components and trapping of functional proteins, and automatically lead to cell death [20]. Curcumin is known to bind many proteins and peptides and modulate their conformation, dynamics, and stability. Thermal aggregation presents an interesting model system to study the aggregatory behavior of proteins. Using HSA as a model protein, the current study explores the potential of curcumin against thermally induced aggregation. Keeping this in view, we studied the protective effect of curcumin on thermally aggregated serum albumin used as a model system, exploring its anti-aggregatory behavior. Incubating HSA at 65°C for increasing time up to 256 hours resulted in thermally aggregated protein at 128 hours, which was validated by intrinsic fluorescence spectra. Thermally aggregated HSA showed maximum ThT as well as a 5 nm red shift in CR absorbance.

Though, incubating the aggregated albumin with curcumin at 15, 30, and 45 µM resulted in quenched ThT and reversal in CR absorbance approaching towards native protein. The secondary structure in denatured HSA was found to have a loss in helical content, but in the presence of curcumin, the α-helix was reverted back significantly. 45 μM was found to be the most effective concentration against thermally aggregated protein. After this, concentration saturation was observed. Morphology of the aggregates was assessed by TEM analysis. The presence of amorphous aggregates was observed, which have decreased α-content relative to their native state, and in the presence of 45 μM curcumin, there was a decrease in aggregated structure, as evident from TEM images. Our studies propose that curcumin may serve as an anti-aggregatory molecule and provide a biochemical basis for other studies that have shown that it is beneficial for disorders that primarily implicate protein aggregation as the major cause of their pathophysiology. Researchers have shown the anti-aggregatory property of curcumin in inhibiting the amyloid fibril formation in proteins [21, 22]. Curcumin has a novel chemical structure that allows it to participate in a number of physical, chemical, and biological processes. The structure has an α, β-unsaturated β-diketo linker, an aromatic o-methoxy phenolic group, and keto-enol tautomerism. The linker gives flexibility, and aromatic groups provide hydrophobicity. The tautomeric structures also influence the hydrophobicity and polarity of the curcumin molecule. All these unique features of curcumin make it able to bind to proteins and inhibit their aggregation [23]. In a spectroscopic and molecular dynamics (MD) study of curcumin binding to β-casein, authors report a face-to-face π-π stacking between the indole ring of tryptophan residues in β-casein and the aromatic rings of curcumin [24]; such interactions are likely to contribute significantly to binding affinity, stability, and specificity in many protein-curcumin complexes. Further studies in this direction will be helpful in delineating mechanistic causes of protein aggregation as well as for the development of disorders that implicate protein aggregates for inducing the diseased state.

Protein aggregation is the process by which native proteins get misfolded and cling to each other to form structurally altered stacks of monomers often referred to as protein aggregates. More recently, accumulating evidence has also demonstrated that non-pathogenic proteins and synthetic polypeptides can form amyloids when appropriate aggregation conditions are provided. The characterization of such partially folded states has important implications for protein folding. A major goal of the present study was to characterize the structural changes occurring on thermal treatment for varying time durations giving rise to the denatured structure of native protein. Our studies have two implications: firstly, that small protein emerges to be a valid model system to investigate the process of aggregation. Secondly, curcumin was found to efficiently have anti-aggregatory properties and a protective effect. The results obtained may have tremendous implications in the development of prospective pharmacologically active derivatives of curcumin, which can be used clinically. There are various reports of curcumin showing strong anti-fibrillation and anti-oligomerization activity on a variety of structural classes of proteins. However, poor blood-brain penetration and instability under physiological conditions limit its use in clinical applications for curing aggregation-related anomalies. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the curcumin-induced structural modulation or aggregation is necessary to explain the underlying mechanism of amyloid-like fibril formation.

The authors are highly thankful for the facilities provided by the Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Life Sciences, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. Maryam Kausar is a recipient of UGC-Non-NET National Fellowship, India.

No external funding was received for conducting this work.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This study did not require formal ethical approval as it did not involve human or animal subjects, and no ethical concerns were identified in conducting this work.

All the data that support the finding of this study are available. The authors shall be solely responsible for any misconduct related to this work.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

.

You are free to share and adapt this material for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit.