J. Biosci. Public Health. 2026; 2(1)

Endophytic bacteria are key mediators of plant growth promotion and pesticide detoxification, yet the genomic mechanisms enabling these dual functions remain underexplored. This study is aimed at exploring new endophytic strains from rice plants from pesticides contaminated soil with their genomic insights. Here, we report the whole-genome sequencing and in-silico functional characterization of Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35, an endophyte isolated from rice plants (Oryza sativa). Genome analysis revealed a 5.18 Mb chromosome with a GC content characteristic of Serratia, harboring coding sequences associated with phytohormone biosynthesis, ACC deaminase activity, siderophore production, phosphate solubilization, oxidative stress tolerance, and systemic resistance induction. Phylogenomic analyses based on ANI, dDDH, and housekeeping genes (recA, gyrB, rpoB, and 16S rRNA) indicate that Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 closely related to Serratia marcescens but exhibits notable evolutionary divergence, suggesting novel genomic features potentially associated with its endophytic lifestyle and agrochemical adaptability. Functional annotation identified an array of xenobiotic-degrading genes, including esterases, amidohydrolases, α/β-hydrolases, and phosphonate-metabolizing operons, implicating the strain in the degradation of organophosphate, pyrethroid, and carbamate pesticides. Virtual screening and molecular docking of key pesticide-degrading proteins confirmed strong binding affinity and plausible enzyme–pesticide interactions, supporting the predicted biotransformation potential. Collectively, the genomic novelty and functional versatility of Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 highlight its promise as a multifunctional endophyte with potential applications in sustainable agriculture, including crop growth promotion, stress tolerance enhancement, and bioremediation of pesticide-contaminated soils.

Endophytic bacteria colonize internal plant tissues without causing apparent harm, providing multifaceted benefits such as plant growth promotion, biocontrol against phytopathogens, and bioremediation of environmental pollutants [1-3]. These microbes enhance nutrient acquisition through phytohormone production (e.g., indole-3-acetic acid), phosphate solubilization, nitrogen fixation, and induction of systemic resistance, thereby boosting crop resilience to abiotic and biotic stresses [4-6]. In sustainable agriculture, endophytes reduce reliance on chemical inputs, helping address global challenges like soil salinity, drought, and pesticide accumulation [7, 8]. Their ability to adapt to diverse and often harsh environmental conditions further positions them as potent alternatives to conventional synthetic fungicides and chemical fertilizers [9].

The genus Serratia exemplifies versatile plant-associated bacteria that inhabit diverse niches, including soil, water, the rhizosphere, and the endosphere [10, 11]. Although some strains act as opportunistic pathogens, many possess plant growth-promoting traits such as IAA biosynthesis, siderophore production, phosphate solubilization, and antagonism through secondary metabolites like prodigiosin, chitinases, proteases, and non-ribosomal peptides [11, 12]. These Serratia endophytes promote root and shoot growth, alleviate heavy metal toxicity, and suppress pathogens such as Fusarium and Rhizoctonia via competition, antibiosis, and induced systemic resistance [11, 12]. Moreover, genomic studies have revealed conserved gene clusters for iron scavenging, quorum sensing, and biofilm formation, all of which facilitate plant colonization [13-15].

Pesticide overuse contaminates agroecosystems, posing risks to soil health, biodiversity, and human welfare. Microbial degradation offers eco-friendly remediation, with endophytes accessing pollutants via plant uptake [16, 17]. Serratia strains degrade chlorinated pesticides (e.g., chlorpyrifos), PAHs (e.g., benzo(a)pyrene), and insecticides via enzymatic pathways involving hydrolases, monooxygenases, and dehalogenases [16-18]. Phylogenomics elucidates Serratia evolution, with 16S rRNA, gyrB, and core-genome trees placing plant-beneficial strains in distinct clades alongside biocontrol species like S. plymuthica and S. marcescens [10, 19, 20]. Although rice endophytes have been extensively investigated for their diversity and functional roles [1-4], endophytic bacteria with confirmed pesticide-degrading capabilities remain poorly characterized and relatively rare. This critical knowledge gap limits the development of effective, eco-friendly bioremediation strategies for pesticide-contaminated agricultural systems. The discovery and characterization of novel pesticide-degrading endophytes are therefore of significant importance for sustainable agriculture, as such microbes can provide dual benefits by facilitating in planta pesticide detoxification while simultaneously enhancing crop resilience under chemically stressed agroecosystems.

In this study, we present an in-depth genomic analysis of the endophytic strain Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35, isolated from healthy rice plants (Oryza sativa) tissues. We characterize its taxonomic position, evolutionary relationships, and plant-beneficial genetic repertoire using state-of-the-art computational tools. Furthermore, we decode the in-silico mechanisms associated with the degradation of major classes of pesticides by identifying putative catabolic genes and metabolic pathways. The findings offer novel insights into the dual functional potential of Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 and highlight its prospects for development as a next-generation bioinoculant with both plant growth-promoting and bioremediation capabilities.

2.1. Isolation and biochemical characterization of endophytic bacteria from rice plants

Endophytic bacterial strains, specifically Serratia sp. HSTU-ABK35, was isolated from the internal tissues of healthy rice plants. The isolation procedure involved cultivating bacterial samples in chlorpyrifos-enriched minimal salt agar media, a method adapted from previous reports, to select for microorganisms capable of thriving in the presence of this pesticide, as descibed methods [1-4]. Subsequent to isolation, the purified bacterial colonies underwent comprehensive biochemical characterization using a panel of standard tests including catalase, oxidase, citrate utilization, methyl red, Voges-Proskauer, urease, triple sugar iron agar, and indole tests. These tests were conducted strictly according to the guidelines outlined in Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology to aid in preliminary identification and metabolic profiling [21]. Further assessment of specific enzyme activities, indicative of their metabolic capabilities, was performed by observing the formation of clear zones around bacterial colonies on specific agar plates, following established protocols [22].

2.2. Whole genome sequencing, taxonomy, genome comparison, and gene prediction

The genomic DNA of the bacterial strains was extracted, and genomic libraries were prepared according to standard protocols as described [17]. Whole genome sequencing was performed using the Illumina MiniSeq System, following established methodologies. The quality of the raw sequencing reads and assembled genome sequences was rigorously assessed through FastQC analysis and monitored via the Base Space Illumina sequence analysis Hub. The annotated genome sequence of the three strains constructed into a complete CDS (coding DNA sequences) map our own developed using Linux operating systems method. For taxonomic classification and phylogenetic analysis, housekeeping genes, specifically recA, gyrB, rpoB, and 16S rRNA, were extracted and analyzed. A robust phylogenetic tree of the strains was constructed with 1000 bootstrap values using MegaXI software. Furthermore, a comprehensive prediction of various functional genes was performed from the PGAP files of the strains. This included genes associated with plant growth-promoting traits (such as N-fixation, P-solubilization, Indole-3-acetic acid and 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase production, and sulfur assimilation), biofilm formation, root colonization mechanisms (chemotaxis and motility), abiotic stress tolerance, and the production of antimicrobial peptides [3, 4].

2.3. Pesticide-degrading protein modeling, virtual screening, and docking

2.3a. Protein modeling and structure validation

Three-dimensional (3D) structures of putative pesticide-degrading proteins from Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 were predicted via homology modeling, utilizing known experimental structures from the Protein Data Bank as templates [3]. Model generation, including template alignment and structural refinement, was performed using established tools such as I-TASSER [4].

Stereochemical quality was assessed using ERRAT, with scores above 80% indicating good quality [23, 25]. VERIFY-3D evaluated the 3D-1D profile, with scores over 80% confirming high structural integrity. Ramachandran plots analyzed amino acid dihedral angles (phi and psi), ensuring a high percentage of residues in favored regions (e.g., >90%) for model reliability [24, 25].

2.3b. Virtual screening

Virtual screening identified potential pesticide binders against predicted protein models. This structure-based approach involved docking a pesticide library into defined protein active sites as previously described [3, 4]. Pesticide compounds and protein receptors were prepared through 3D structure generation, energy minimization, and format conversion [3, 4, 26]. The screening process employed docking software to predict optimal binding poses and assign binding affinity scores (e.g., Kcal/mol) [23]. This resulted in a ranked list of compounds based on predicted binding energies, facilitating the prioritization of potential interactions.

2.3c. Molecular docking and catalytic interaction analysis

Detailed molecular docking was performed on selected protein-pesticide complexes to elucidate specific molecular interactions [27]. Docking algorithms sampled various ligand conformations within protein binding sites, predicting stable complex structures and binding energies [21, 24]. The analysis focused on identifying key stabilizing interactions, including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and salt bridges. Emphasis was placed on identifying catalytic triads or diads, critical enzymatic motifs, to infer potential degradation mechanisms and roles of specific active site residues [3, 4].

3.1. Biochemical characterization of Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35

The biochemical profiling of Serratia sp. strain HSTU-ABk35 revealed a broad range of positive enzymatic and metabolic activities (Table 1), supporting its taxonomic placement within the genus Serratia and highlighting its functional versatility. The isolate tested positive for oxidase, catalase, and citrate utilization, indicating an active aerobic metabolism and the ability to use citrate as a sole carbon source. Positive MIU reactions further suggested motility and indole utilization capacity, while the absence of mortality response confirmed the non-lethal nature of the strain under the tested conditions.

The strain exhibited a positive urease reaction, reflecting its potential to hydrolyze urea and contribute to nitrogen cycling. In the IMViC series, Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 showed a positive Voges–Proskauer (VP) reaction and a negative methyl red (MR) test, indicating a butanediol fermentation pathway rather than mixed-acid fermentation. The triple sugar iron (TSI) test was positive, suggesting efficient carbohydrate utilization without hydrogen sulfide production.

Table 1: Biochemical analyses of Serratia sp. HSTU-Abk35.

| Oxidase | Citrate | Catalase | MIU | Mortality | Urease | VP | MR | TSI | Lactose | Sucrose | Dextrose | CMCase | Xylanase | Amylase | Protease | |

| Serratia sp. strain HSTU-ABk35 | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

Carbohydrate fermentation assays demonstrated the ability of the strain to metabolize lactose, sucrose, and dextrose, indicating metabolic flexibility toward diverse carbon sources. Notably, the isolate expressed strong extracellular hydrolytic enzyme activities, including CMCase (cellulase), xylanase, amylase, and protease. The presence of these enzymes underscores the strain’s capacity to degrade complex polysaccharides and proteins, which may enhance nutrient mobilization and ecological adaptability in plant-associated or soil environments. Overall, the biochemical traits of Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 reflect a metabolically robust bacterium with multifunctional enzymatic potential.

3.2. Phylogenetic taxonomy of the endophytic bacteria

3.2a. Genome annotation and phylogenetic relationship of the strains

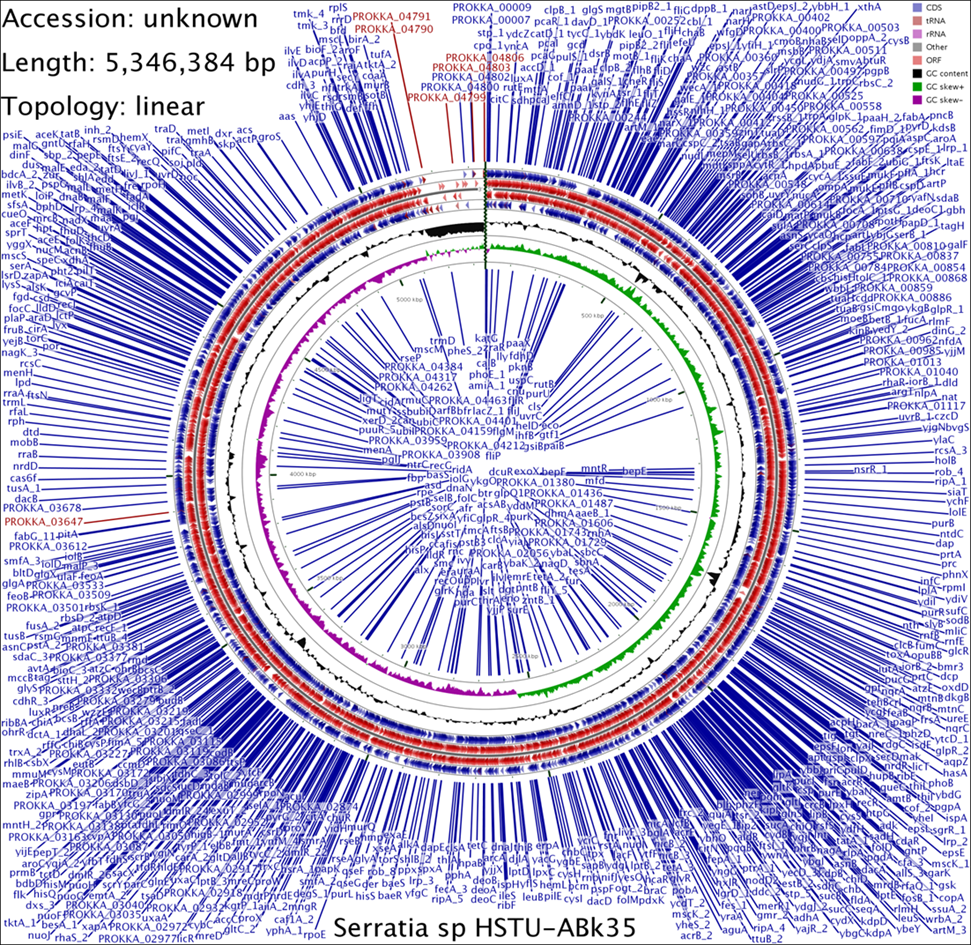

The annotated genome sequence of the three strains revealed a complete CDS (coding DNA sequences) map with genetic repertoire of predicted genes distributed across the genome (Figure 1). The genome map of Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 shows a linear chromosome of 5,346,384 bp with a dense and uniform distribution of coding sequences (CDSs)across both strands. Protein-coding genes are tightly packed throughout the genome, indicating efficient genome organization and high metabolic capacity. The genome of the strain has no large intergenic gaps, indicating strong coding potential. CDSs are evenly distributed on both forward and reverse strands, suggesting balanced transcriptional organization. The genome map shows distinct GC content and GC skew patterns, with localized deviations that may represent functionally specialized or horizontally acquired regions. Numerous CDS clusters are visible across the chromosome, consistent with operon-based gene organization typical of bacteria. The abundance of annotated enzymatic CDSs (e.g., oxidoreductases, hydrolases, transferases) highlights the strain’s metabolic versatility and adaptive potential.

Figure 1. A CDS (coding DNA sequences) map of for Serratia sp. strain HSTU-Abk35.

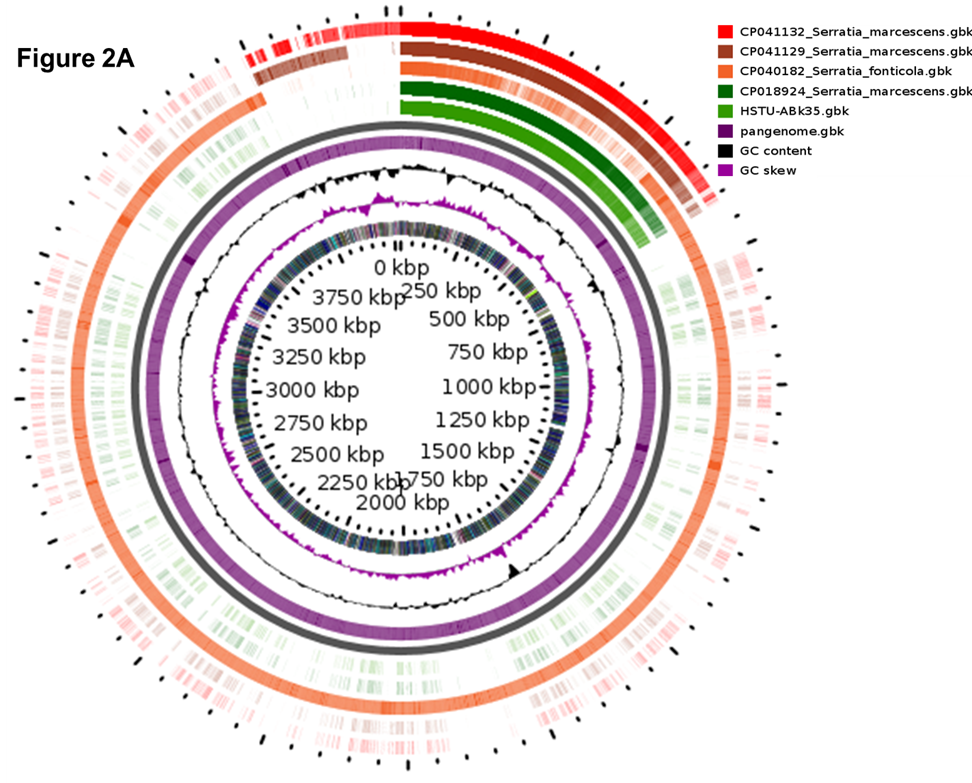

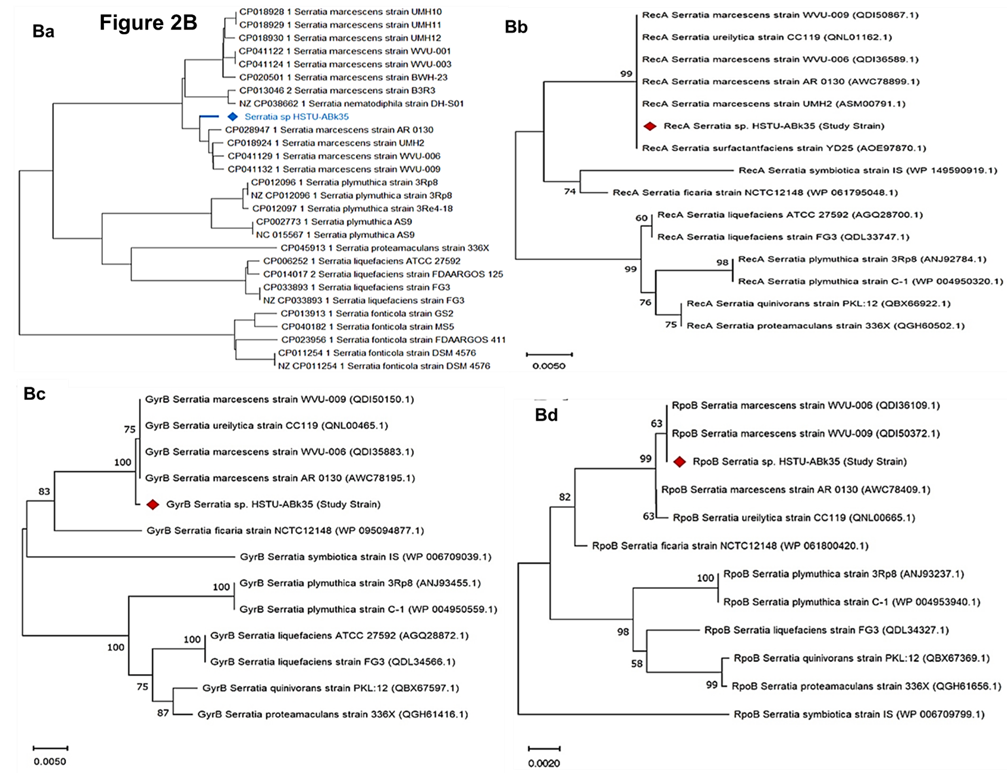

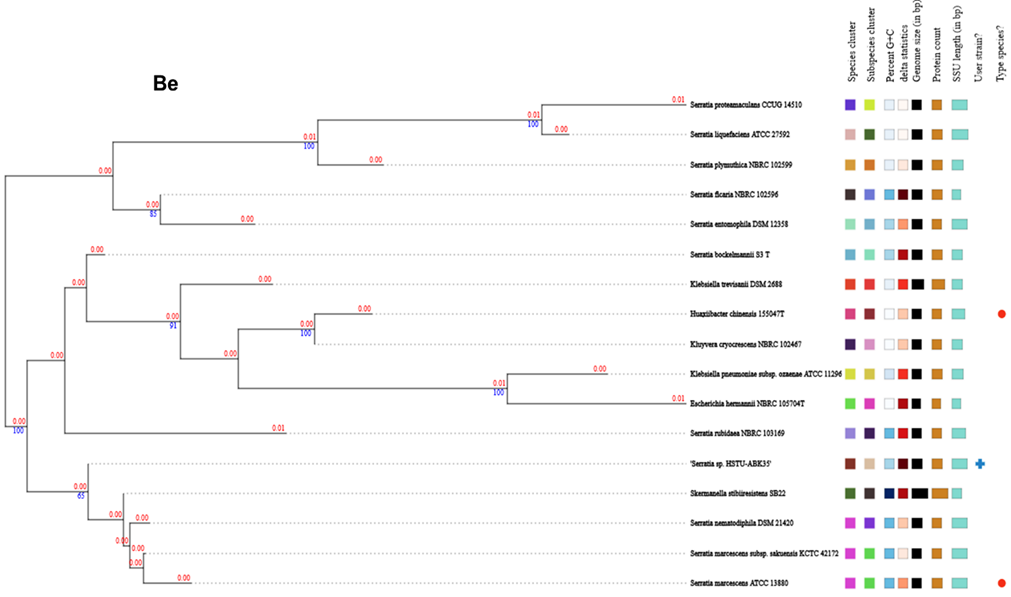

As seen in Figure 2A, circular plot of the three strains pangenome plot the pink color slot identified as pan-genome and white space indicates a region missing in the specified genome. The circular plot clearly intimate that a several portions of the genome sequence of Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35were not similar compared with other six closest strains (Figure 2A).

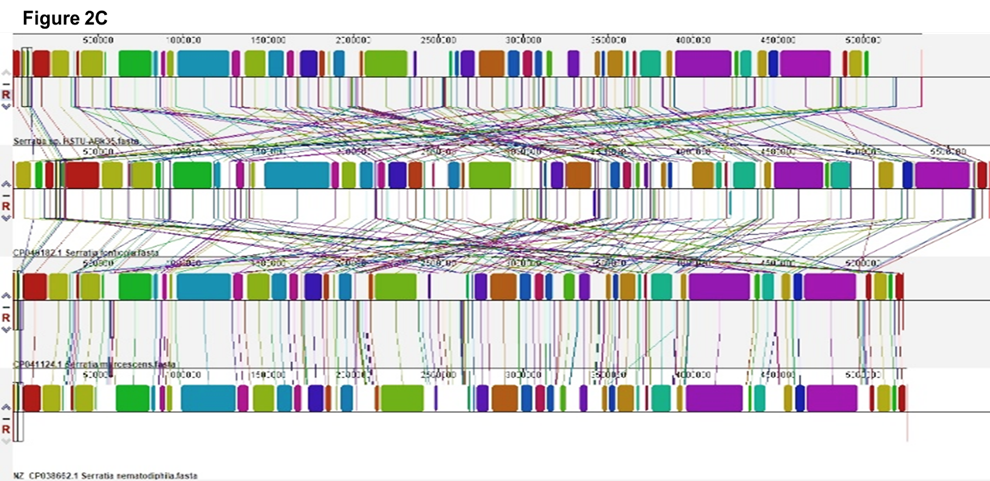

Figure 2. Genome comparison and phylogenetic analysis of the strain Serratia sp. HSTU-Abk35. (A) Pangenome analysis of the strain. (B) Phylogeny of the strain, (Ba) Whole genome phylogenetic tree of the strain; (Bb) phylogenetic tree based on housekeeping gene recA; (Bc) phylogenetic tree based on housekeeping gene gyrB; (Bd) phylogenetic tree based on housekeeping gene rpoB; (Be) phylogenetic tree based on housekeeping gene (16S rRNA) analysis of Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35. (C) Progressive Mauve alignment (LCBs) of the strain Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 with their nearest homologs.

The whole genome phylogenetic tree of strain, Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 showed that it was placed completely in a single node that is originated from two parental node i.e. one node lead by strain, Serratia marcescens AR0130 and other node represented by strain, Serratia nematodiphila DS-SO1 (Figure 2Ba). The pairwise highest ANI blast (ANIb) score of strain, Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 was hit with Serratia ureilytica (CP060276.1) 99.12%, followed by Serratia marcescens (CP041132.1) 98.82% (Table 2a). Furthermore, the dDDH analysis of strain, Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 with its nearest homologs strain, Serratia nematodiphila DSM21420 showed 77.4% dDDH value, and 0.67% G+C content, followed by strain, Serratia marcescens sub sp. sakuensis KCTC 42172 showed 74.6% dDDH value, and 0.78% G+C content (Table 2b), while recA gene of strain, Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 was placed in the same node with recA gene of strains, Serratia marcescens UMH2 and Serratia ureilytica CC119 with 99% similarity (Figure 2Bb). In addition, gyrB gene of strain, Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 was placed in a separate node from strains, Serratia marcescens and Serratia ficaria (Figure 2Bc) and rpoB gene was placed in the same node with strain, S. marcescens (Figure 2Bd). In addition, the 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis of the strain had shown nearest relationship, but separate cluster, with Serratia rubidae (Figure 2Be). Therefore, the strain, Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 might belongs to Serratia marcescens with evolutionary history.

Multiple genome alignment analysis was conducted to expand our understanding of the genomic features of Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 (Figure 2C). Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 strains genome was compared with another four individual nearest strains. Each genome isorganized horizontally with homologous segment outlined as colored rectangles. Each same color block represents a locally collinear block (LCB) or homologous region shared among genomes. The locally collinear block (LCB) of Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35, genome is not totally meet with locally collinear blocks of genomes taken for genomic comparison. Rearrangement of genomic regions was observed between the two genomes in terms of collinearity. As seen, the study strain shared highest homologous region with Serratia marcescens for Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35.

Table 2A. Average nucleotide identity (ANIb) of Serratia sp. strain HSTU-ABk35.

| Serratia_sp._HSTU-ABk35 | CP006252.1_Serratia_liquefaciens | CP012096.1_Serratia_plymuthica | CP016948.1_Serratia_surfactantfaciens | CP018924.1_Serratia_marcescens | CP028947.1_Serratia_marcescens | CP033893.1_Serratia_liquefaciens | CP038467.1_Serratia_quinivorans | CP041129.1_Serratia_marcescens | CP041132.1_Serratia_marcescens | CP045913.1_Serratia_proteamaculans | CP060276.1_Serratia_ureilytica | NZ_AP019531.1_Serratia_symbiotica | NZ_CP053398.1_Serratia_plymuthica | NZ_LT906479.1_Serratia_ficaria | |

| Serratia_sp._HSTU-ABk35.fasta | * | 82.84 | 83.44 | 93.61 | 97.66 | 97.6 | 82.85 | 82.77 | 97.58 | 97.67 | 82.61 | 97.66 | 81.37 | 83.39 | 85.95 |

| CP006252.1_Serratia_liquefaciens | 82.81 | * | 86.13 | 82.71 | 82.87 | 82.87 | 98.31 | 87.54 | 82.9 | 82.82 | 87.54 | 82.88 | 80.87 | 86.15 | 83.39 |

| CP012096.1_Serratia_plymuthica | 83.42 | 86.15 | * | 83.43 | 83.43 | 83.48 | 86.08 | 86.31 | 83.47 | 83.52 | 86.14 | 83.56 | 81.13 | 98.38 | 84.6 |

| CP016948.1_Serratia_surfactantfaciens | 93.69 | 82.8 | 83.48 | * | 93.52 | 93.6 | 82.84 | 82.68 | 93.51 | 93.5 | 82.59 | 93.66 | 81.55 | 83.48 | 85.75 |

| CP018924.1_Serratia_marcescens | 97.59 | 82.91 | 83.53 | 93.45 | * | 98.18 | 82.96 | 82.83 | 98.74 | 98.82 | 82.69 | 98.33 | 81.33 | 83.53 | 85.89 |

| CP028947.1_Serratia_marcescens | 97.74 | 83.04 | 83.63 | 93.59 | 98.3 | * | 82.94 | 82.8 | 98.32 | 98.37 | 82.73 | 99.12 | 81.46 | 83.62 | 86.05 |

| CP033893.1_Serratia_liquefaciens | 82.75 | 98.2 | 86.05 | 82.67 | 82.81 | 82.65 | * | 87.5 | 82.69 | 82.67 | 87.29 | 82.82 | 81.13 | 86.13 | 83.5 |

| CP038467.1_Serratia_quinivorans | 82.68 | 87.59 | 86.42 | 82.64 | 82.79 | 82.69 | 87.64 | * | 82.78 | 82.78 | 95.33 | 82.78 | 80.93 | 86.34 | 83.76 |

| CP041129.1_Serratia_marcescens | 97.62 | 82.94 | 83.61 | 93.5 | 98.76 | 98.2 | 82.91 | 82.76 | * | 99.06 | 82.67 | 98.31 | 81.42 | 83.6 | 85.82 |

| CP041132.1_Serratia_marcescens | 97.7 | 82.95 | 83.64 | 93.48 | 98.74 | 98.24 | 82.88 | 82.75 | 99.01 | * | 82.68 | 98.36 | 81.56 | 83.56 | 85.84 |

| CP045913.1_Serratia_proteamaculans | 82.46 | 87.56 | 86.25 | 82.51 | 82.57 | 82.54 | 87.46 | 95.33 | 82.56 | 82.55 | * | 82.64 | 80.76 | 86.21 | 83.47 |

| CP060276.1_Serratia_ureilytica | 97.6 | 82.97 | 83.64 | 93.47 | 98.27 | 98.94 | 82.98 | 82.93 | 98.19 | 98.24 | 82.79 | * | 81.39 | 83.68 | 86.07 |

| NZ_AP019531.1_Serratia_symbiotica | 82.6 | 81.73 | 82.41 | 82.64 | 82.52 | 82.51 | 81.94 | 81.87 | 82.5 | 82.5 | 81.71 | 82.52 | * | 82.38 | 83.51 |

| NZ_CP053398.1_Serratia_plymuthica | 83.38 | 86.08 | 98.32 | 83.48 | 83.48 | 83.5 | 86.17 | 86.25 | 83.5 | 83.47 | 86.11 | 83.58 | 81.29 | * | 84.4 |

| NZ_LT906479.1_Serratia_ficaria | 86.39 | 83.84 | 85.07 | 86.39 | 86.32 | 86.36 | 83.92 | 84.11 | 86.27 | 86.28 | 83.81 | 86.41 | 82.65 | 85 | * |

Table 2B. Digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) for species determination of Serratia sp. strain HSTU-ABk35.

| Subject strain | dDDH (d0, in %) | C.I. (d0, in %) | dDDH (d4, in %) | C.I. (d4, in %) | dDDH (d6, in %) | C.I. (d6, in %) | G+C content difference (in %) |

| Serratia nematodiphila DSM 21420 | 77.6 | [73.6 -81.1] | 63.0 | [60.1 -65.8] | 77.4 | [73.9 -80.5] | 0.67 |

| Serratia marcescens subsp. sakuensis KCTC 42172 | 74.5 | [70.5 -78.1] | 62.3 | [59.4 -65.1] | 74.6 | [71.1 -77.7] | 0.78 |

| Serratia marcescens ATCC 13880 | 75.7 | [71.7 -79.3] | 61.5 | [58.6 -64.3] | 75.4 | [71.9 -78.5] | 0.97 |

| Serratia bockelmannii S3 T | 70.8 | [66.9 -74.5] | 61.2 | [58.4 -64.0] | 71.2 | [67.7 -74.4] | 0.18 |

| Serratia ficaria NBRC102596 | 56.1 | [52.6 -59.6] | 34.3 | [31.9 -36.9] | 50.5 | [47.5 -53.6] | 1.04 |

| Serratia entomophila DSM 12358 | 58.6 | [54.9 -62.1] | 33.4 | [31.0 -35.9] | 51.9 | [48.9 -55.0] | 0.05 |

| Serratia plymuthica NBRC 102599 | 45.7 | [42.3 -49.1] | 28.1 | [25.7 -30.6] | 40.3 | [37.3 -43.3] | 2.91 |

| Serratia liquefaciensATCC 27592 | 48.7 | [45.3 -52.2] | 27.1 | [24.7 -29.5] | 42.0 | [39.0 -45.0] | 3.54 |

| Serratia proteamaculans CCUG 14510 | 47.2 | [43.8 -50.7] | 26.9 | [24.5 -29.4] | 40.9 | [37.9 -43.9] | 3.74 |

| Serratia rubidaea NBRC 103169 | 36.5 | [33.1 -40.0] | 26.4 | [24.1 -28.9] | 33.0 | [30.1 -36.1] | 0.43 |

| Skermanella stibiiresistens SB22 | 12.6 | [9.9 -15.8] | 23.7 | [21.4 -26.2] | 13.0 | [10.7 -15.7] | 6.99 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae ATCC 11296 | 17.1 | [14.1 -20.7] | 20.7 | [18.5 -23.1] | 17.0 | [14.4 -19.9] | 1.61 |

| Klebsiella trevisanii DSM2688 | 15.5 | [12.6 -19.0] | 20.7 | [18.5 -23.1] | 15.6 | [13.1 -18.5] | 3.72 |

| Escherichia hermannii NBRC 105704T | 15.5 | [12.6 -19.0] | 20.4 | [18.2 -22.8] | 15.5 | [13.0 -18.4] | 4.8 |

| Huaxiibacter chinensis155047T | 15.1 | [12.2 -18.5] | 20.2 | [18.0 -22.6] | 15.2 | [12.7 -18.1] | 5.16 |

| Kluyvera cryocrescens NBRC 102467 | 15.5 | [12.6 -19.0] | 20.1 | [17.9 -22.5] | 15.6 | [13.0 -18.5] | 5.02 |

3.2b. Plant growth promoting genes of pesticide degrading endophytic bacteria

The assembled genome of the respective strains, Serratia sp. HSTU-Abk35 (Table 3a) encoded a number of nitrogen-fixing, nitrosative stress, and nitrogen metabolism regulatory proteins, including iscU, nifJS, nsrR, glnK, glnD, and ptsN . In particular, the strains possessed the genes encoding nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, and associated transporters, ACC-deaminase, superoxide dismutase, high-affinity siderophore (enterobactin), IAA producing enzyme, phosphate and trehalose metabolic enzymes, sulfur and ammonia assimilatory, and biofilm forming. The assembled genome of these three strains revealed the presence of root-colonizing genes. In addition, the genome Serratia sp. HSTU-Abk35 contained annotated systemic resistance inducer genes, including VOCs (volatile compounds) genes, and synthetic genes, such as methanethiol (metH), 2,3-butanediol (ilvBNACYDM), isoprene (gcpE/ispG, ispE), acetolactate decarboxylase (budA), spermidine synthesis (speEABD), and oxidoreductase and hydrolase (amyA) genes. A set of antimicrobial peptide synthesis genes, such as pagP, sapBC, lipA, lipB, and amyA genes, was observed in the annotated genome (Table 3a).

Table 3A. Genes associated with plant growth promotion (PGP) available in genome Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35.

| PGP activities description |

| Gene annotation | Chromosome location | Locus Tag | E.C. number |

| Nitrogen fixation | nifJ | Pyruvate: ferredoxin (flavodoxin) oxidoreductase | 292050..295583 | GPJ58_11545 | - |

| nifS | cysteine desulfurase | 135906..137120 | GPJ58_13915 | 2.8.1.7 | |

| iscU | Fe-S cluster assembly scaffold | 135495..135881 | GPJ58_13910 | - | |

| Nitrosative stress | nsrR | Nitric oxide sensing transcriptional repressor | 14192..14617 | GPJ58_18580 | - |

| glnK | P-II family nitrogen regulator | 196845..197183 | GPJ58_09290 | - | |

nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, and associated transporters | - | nitrate reductase subunit alpha | GPJ58_01815 | GPJ58_01815 | 1.7.99.4 |

| narH | nitrate reductase subunit beta | 407283..408827 | GPJ58_01820 | 1.7.99.4 | |

| narJ | nitrate reductase molybdenum cofactor assembly chaperone | 408824..409546 | GPJ58_01825 | - | |

| narI | respiratory nitrate reductase subunit gamma | 409549..410226 | GPJ58_01830 | 1.7.99.4 | |

| - | nitrate reductase | 155594..156142 | GPJ58_16505 | - | |

| NirD | nitrite reductase small subunit NirD | 39471..39797 | GPJ58_17880 | - | |

| - | nitrate reductase subunit alpha | 149433..151118 | GPJ58_16480 | 1.7.99.4 | |

| Acetolactate decarboxylase | budA | Acetolactate decarboxylase | 151151..151930 | GPJ58_16485 | 4.1.1.5 |

| Nitrogen metabolism regulatory protein | glnD | Bifunctional uridylyl removing protein | 42171..44834 | GPJ58_22755 | 2.7.7.59 |

| glnB | Nitrogen regulatory protein P-II | 158223..158561 | GPJ58_14010 | - | |

| ptsN | Nitrogen regulatory protein PtsN | 62566..63012 | GPJ58_15005 | - | |

| Ammonia assimilation | gltB | glutamate synthase large subunit | 83748..88208 | GPJ58_15135 | 1.4.1.13 |

| gltS | sodium/glutamate symporter | 24791..26002 | GPJ58_19400 | ||

| amtB | Ammonium transporter AmtB | 197219..198505 | GPJ58_09295 | - | |

| ACC deaminase | dcyD | D-cysteine desulfhydrase | 350129..351121 | GPJ58_01600 | 4.4.1.15 |

| rimM | ribosome maturation factor RimM | 13791..14339 | GPJ58_11820 | - | |

| Siderophore | |||||

| Siderophore enterobactin | fes | enterochelin esterase | 125919..127181 | GPJ58_10850 | 3.1.1.- |

| entC | isochorismate synthase EntC | 29818..31023 | GPJ58_22940 | 5.4.4.2 | |

| entS | enterobactin transporter EntS | 115761..117044 | GPJ58_10835 | - | |

| entE | 2,3-dihydroxybenzoyl)adenylate synthase | 31031..32659 | GPJ58_22945 | 2.7.7.58 | |

| fhuA | ferrichrome porin FhuA | 64477..66669 | GPJ58_21180 | - | |

| fhuB | Fe (3+)-hydroxamate ABC transporter permease FhuB | 68419..70407 | GPJ58_21195 | - | |

| fhuC | Fe3+-hydroxamate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | 66717..67514 | GPJ58_21185 | - | |

| fhuD | Fe (3+)-hydroxamate ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 67514..68422 | GPJ58_21190 | - | |

| tonB | TonB system transport protein TonB | 603377..604120 | GPJ58_02810 | - | |

| fepB | Fe2+-enterobactin ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 143531..144538 | GPJ58_16455 | - | |

| fepG | iron-enterobactin ABC transporter permease | 145809..146846 | GPJ58_16465 | - | |

| exbD | TonB system transport protein ExbD | 191384..191806 | GPJ58_15620 | - | |

| rpoA | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit alpha | 11203..12192 | GPJ58_23825 | 2.7.7.6 | |

| rpoB | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta | 4163..8191 | GPJ58_23520 | 2.7.7.6 | |

| exbB | tol-pal system-associated acyl-CoA thioesterase | 190403..191380 | GPJ58_15615 | - | |

| Plant hormones | |||||

| IAA production | trpCF | bifunctional indole-3-glycerol-phosphate synthase TrpC | 611973..613334

| GPJ58_02860 | 4.1.1.48/5.3.1.24 |

| trpS | tryptophan--tRNA ligase | 462106..463113 | GPJ58_05220 | 6.1.1.2 | |

| trpA | tryptophan synthase subunit alpha | 609935..610741 | GPJ58_02850 | 4.2.1.20 | |

| trpD | bifunctional anthranilate synthase glutamate amido transferase component | 613338..614336 | GPJ58_02865 | 2.4.2.18/4.1.3.27 | |

| Phosphate metabolism | pitA | inorganic phosphate transporter PitA | 170376..171878 | GPJ58_18405 | - |

| pstS | phosphate ABC transporter substrate-binding protein PstS | 171797..172837 | GPJ58_17535 | - | |

| pstC | phosphate ABC transporter permease PstC | 170749..171705 | GPJ58_17530 | - | |

| pstA | phosphate ABC transporter permease PstA | 169857..170747 | GPJ58_17525 | - | |

| pstB | phosphate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein PstB | 169032..169808 | GPJ58_17520 | - | |

| phoU | phosphate signaling complex protein PhoU | 168286..169020 | GPJ58_17515 | 3.5.2.6 | |

| ugpB | sn-glycerol-3-phosphate ABC transporter substrate-binding protein UgpB | 34307..35626

| GPJ58_21855 | -- | |

| ugpE | sn-glycerol-3-phosphate ABC transporter substrate-binding protein UgpE | 32499..33344 | GPJ58_21845 | - | |

| phoA | alkaline phosphatase | 328821..330248 | GPJ58_04570 | 3.1.3.1 | |

| phoB | phosphate response regulator transcription factor PhoB | 135120..135809 | GPJ58_09005 | - | |

| phoR | phosphate regulon sensor histidine kinase PhoR | 135834..137150 | GPJ58_09010 | 2.7.13.3 | |

| ppx | exopolyphosphatase | 54567..56117 | GPJ58_13560 | 3.6.1.11 | |

| ppk1 | polyphosphate kinase 1 | 52493..54556 | GPJ58_13555 | 2.7.4.1 | |

| phoH | phosphate starvation-inducible protein PhoH | 364084..364872 | GPJ58_01645 | - | |

| pntA | Re/Si-specific NAD(P)(+) transhydrogenase subunit alpha | 267170..268699 | GPJ58_11430 | 1.6.1.2 | |

| pntB | Re/Si-specific NAD(P)(+) transhydrogenase subunit beta" | 265765..267159 | GPJ58_11425 | - | |

| phoQ | two-component system sensor histidine kinase PhoQ | 171572..173029 | GPJ58_06810 | 2.7.13.3 | |

| Biofilm formation | tomB | Hha toxicity modulator TomB | 216969..217337 | GPJ58_09415 | - |

| luxS | S-ribosylhomocysteine lyase | 18539..19054 | GPJ58_11845 | 4.4.1.21 | |

| murJ | Murein biosynthesis integral membrane protein MurJ | 477332..478867 | GPJ58_02200 | - | |

| flgH | Flagellar basal body L-ring protein FlgH | 320491..321192 | GPJ58_01450 | - | |

| flgJ | Flagellar assembly peptidoglycan hydrolase FlgJ | 322303..323247 | GPJ58_01460 | 3.2.1.- | |

| flgL | Flagellar hook-filament junction protein FlgL | 325163..326122 | GPJ58_01470 | - | |

| flgM | Flagellar biosynthesis anti-sigma factor FlgM | 314793..315104 | GPJ58_01410 | - | |

| flgA | Flagellar basal body P-ring formation protein | 315233..315886 | GPJ58_01415 | - | |

| flgB | Flagellar basal body rod protein FlgB | 316047..316460 | GPJ58_01420 | - | |

| flgI | Flagellar basal body P-ring protein FlgI | 321203..322303 | GPJ58_01455 | - | |

| flgG | Flagellar basal-body rod protein FlgG | 319625..320407 | GPJ58_01445 | - | |

| motA | Flagellar motor stator protein MotA | 297739..298629 | GPJ58_01320 | - | |

| motB | Flagellar motor protein MotB | 298626..299690 | GPJ58_01325 | - | |

| efp | elongation factor P | 52848..53414 | GPJ58_23055 | - | |

| hfq | RNA chaperone Hfq | 8280..8588 | GPJ58_18550 | - | |

Sulfur assimilation and metabolism

| cysZ | sulfate transporter CysZ | 162264..163022 | GPJ58_16540 | - |

| cysK | cysteine synthase A | 163208..164176 | GPJ58_16545 | 2.5.1.47 | |

| cysM | cysteine synthase CysM | 169505..170386 | GPJ58_16575 | 2.5.1.47 | |

| cysA | sulfate/thiosulfate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein CysA | 170468..171556 | GPJ58_16580 | - | |

| cysW | sulfate/thiosulfate ABC transporter permease CysW" | 171546..172421 | GPJ58_16585 | - | |

| cysC | adenylyl-sulfate kinase | 47986..48675 | GPJ58_12010 | 2.7.1.25 | |

| cysN | sulfate adenylyl transferase subunit CysN | 48614..50041 | GPJ58_12015 | 2.7.7.4 | |

| cysD | sulfate adenylyl transferase subunit CysD | 50053..50961 | GPJ58_12020 | 2.7.7.4 | |

| cysH | Phosphor adenosine phosphosulfate reductase | 53802..54536 | GPJ58_12035 | 1.8.4.8 | |

| cysI | assimilatory sulfite reductase (NADPH) | 54598..56313 | GPJ58_12040 | 1.8.1.2 | |

| cysJ | NADPH-dependent assimilatory sulfite reductase flavoprotein subunit | 56313..58112 | GPJ58_12045 | 1.8.1.2 | |

| cysT | sulfate/thiosulfate ABC transporter permease CysT | 172421..173260 | GPJ58_16590 | - | |

| cysE | serine O-acetyltransferase | 70866..71687 | GPJ58_19635 | 2.3.1.30 | |

| cysQ | 3'(2'),5'-bisphosphate nucleotidase CysQ | 28840..29583 | GPJ58_18675 | 3.1.3.7 | |

| cysK | cysteine synthase A | 163208..164176 | GPJ58_16545 | 2.5.1.47 | |

| cysS | cysteine--tRNA ligase | 270209..271594 | GPJ58_09655 | 6.1.1.16 | |

| fdxH | formate dehydrogenase subunit beta | 96369..97271 | GPJ58_17185 | - | |

| Antimicrobial peptide | pagP | lipid IV(A) palmitoyltransferase PagP | 81959..82549 | GPJ58_08735 | 2.3.1.251 |

| sapC | peptide ABC transporter permease SapC | 318687..319577 | GPJ58_11670 | - | |

| sapB | peptide ABC transporter permease SapB | 317735..318700 | GPJ58_11665 | - | |

| Antibiotic | lipA | lipoyl synthase | 305309..306274 | GPJ58_09830 | 2.8.1.8 |

| lipB | lipoyl(octanoyl) transferase LipB | 306267..306926 | GPJ58_09835 | 2.3.1.181 | |

| amyA | alpha-amylase | 478286..479776 | GPJ58_05310 | 3.2.1.1 | |

| Synthesis of resistance inducers | |||||

| Methanethiol | metH | methionine synthase | 75928..79623 | GPJ58_21630 | 2.1.1.13 |

| 2,3-butanediol | ilvB | acetolactate synthase large subunit | 143775..145469 | GPJ58_12420 | - |

| ilvN | acetolactate synthase small subunit | 145473..145766 | GPJ58_12425 | 2.2.1.6 | |

| ilvA | Serine, threonine dehydratase | 20005..21549 | GPJ58_23430 | 4.3.1.19 | |

| ilvC | ketol-acid reductoisomerase | 16151..17626 | GPJ58_23410 | 1.1.1.86 | |

| ilvY | HTH-type transcriptional activator IlvY | 17795..18685 | GPJ58_23415 | - | |

| ilvD | Dihydroxy-acid dehydratase | 21555..23405 | GPJ58_23435 | 4.2.1.9 | |

| ilvM | acetolactate synthase 2 small subunits | 24463..24720 | GPJ58_23445 | 2.2.1.6 | |

| isoprene | gcpE/ ispG | flavodoxin-dependent (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl-diphosphate synthase | 124638..125759 | GPJ58_13850 | 1.17.7.1 |

| ispE | 4-(cytidine 5'-diphospho)-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase | 138070..138936 | GPJ58_06655 | 2.7.1.148 | |

acetolactate decarboxylase | budA | acetolactate decarboxylase | 151151..151930 | GPJ58_16485 | 4.1.1.5 |

spermidine synthesis | speE | Polyamine aminopropyltransferase | 41546..42409 | GPJ58_21075 | 2.5.1.16 |

| speA | biosynthetic arginine decarboxylase | 73053..75029 | GPJ58_21215 | 4.1.1.19 | |

| speB | agmatinase | 75224..76144 | GPJ58_21220 | 3.5.3.11 | |

| speD | adenosylmethionine decarboxylase | 40724..41518 | GPJ58_21070 | 4.1.1.50 | |

| Symbiosis-related | pyrC | dihydroorotase | 42200..43246 | GPJ58_06120 | 3.5.2.3 |

| gcvT | glycine cleavage system aminomethyltransferase | 63760..64857

| GPJ58_20715 | 2.1.2.10 | |

| phnC | phosphonate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | 461155..461988 | GPJ58_05215 | - | |

| tatA | Sec-independent protein translocase subunit TatA | 16209..16472 | GPJ58_21765 | - | |

| zur | Transcriptional repressor /zinc uptake transcriptional repressor | 32707..33219 | GPJ58_21465 | - | |

| Oxidoreductase | sodB | superoxide dismutase [Fe] | 353029..353607 | GPJ58_07710 | 1.15.1.1 |

| gpx | glutathione peroxidase | 302928..303479 | GPJ58_07465 | 1.11.1.9 | |

| osmC | peroxiredoxin OsmC | 147889..148491 | GPJ58_09060 | 1.11.1.15 | |

| Hydrolase | ribA | GTP cyclohydrolase II | 70027..70650 | GPJ58_17050 | 3.5.4.25 |

| folE | GTP cyclohydrolase I FolE | 304605..305270 | GPJ58_04430 | 3.5.4.16 | |

| bglF | PTS beta-glucoside transporter subunit IIABC | 62500..64365 | GPJ58_17020 | ||

| bglX | beta-glucosidase BglX | 497320..499617 | GPJ58_05410 | 3.2.1.21 | |

| malZ | maltodextrin glucosidase | 144010..145833 | GPJ58_09050 | 3.2.1.20 | |

| bglA | 6-phospho-beta-glucosidase | 166494..167930 | GPJ58_11005 | 3.2.1.86 | |

| gdhA | NADP-specific glutamate dehydrogenase | 175414..176757 | GPJ58_18430 | 1.4.1.4 | |

| - | cellulase | 31860..32972 | GPJ58_16885 | 3.2.1.4 | |

| amyA | alpha-amylase | 478286..479776 | GPJ58_05310 | 3.2.1.1 | |

| Root colonization | |||||

| Chemotaxis | malE | maltose/maltodextrin ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 49069..50262 | GPJ58_21540 | - |

cheY

| Two-component system response regulator/ chemotaxis protein CheY | 307861..308250 | GPJ58_01360 | -

| |

| cheB | chemotaxis-specific protein-glutamate methyltransferase CheB | 306709..307758 | GPJ58_01355 | 3.1.1.61 | |

| cheW | chemotaxis protein CheW | 301741..302241 | GPJ58_01335 | - | |

| cheA | chemotaxis protein CheA | 299687..301708 | GPJ58_01330 | - | |

| rbsB | ribose ABC transporter substrate-binding protein RbsB | 197755..198642 | GPJ58_17650 | - | |

| Motility | flhA | flagellar biosynthesis protein FlhA | 310933..313011 | GPJ58_01385 | - |

| flhB | flagellar type III secretion system protein | 309789..310940 | GPJ58_01380 | - | |

| flhC | Transcriptional activator FlhC/ flagellar transcriptional regulator | 297012..297593 | GPJ58_01315 | - | |

| flhD | flagellar transcriptional regulator FlhD | 296650..297009 | GPJ58_01310 | - | |

| fliZ | flagella biosynthesis regulatory protein FliZ | 349495..350004 | GPJ58_01595 | - | |

| fliD | Flagellar filament capping protein FliD | 345803..347203 | GPJ58_01580 | - | |

| fliS | flagellar export chaperone Proein | 345366..345776 | GPJ58_01575 | - | |

| fliE | flagellar hook-basal body complex protein FliE | 337952..338266 | GPJ58_01540 | - | |

| fliF | flagellar basal body M-ring protein FliF | 335942..337636 | GPJ58_01535 | - | |

| fliG | flagellar motor switch protein FliG | 334953..335945 | GPJ58_01530 | - | |

| fliT | flagella biosynthesis regulatory protein FliT | 344998..345366 | GPJ58_01570 | ||

| fliH | flagellar assembly protein FliH | 334256..334960 | GPJ58_01525 | - | |

| fliL | flagellar basal body-associated protein FliL | 330545..331030 | GPJ58_01505 | - | |

| fliM | flagellar motor switch protein FliM | 329535..330539 | GPJ58_01500 | - | |

| fliP | Flagellar biosynthetic protein FliP/flagellar type III secretion system pore protein | 327964..328725 | GPJ58_01485 | - | |

| fliQ | flagellar biosynthesis protein FliQ | 327673..327942 | GPJ58_01480 | - | |

| Adhesive structure | hofC | protein transport protein HofC | 94559..95758 | GPJ58_12200 | - |

| Superoxide dismutase | sodA | superoxide dismutase [Mn] | 100759..101379 | GPJ58_17195 | 1.15.1.1 |

| sodB | superoxide dismutase [Fe] | 353029..353607 | GPJ58_07710 | 1.15.1.1 | |

| sodC | superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] SodC2 | 365763..366284 | GPJ58_07775 | 1.15.1.1 | |

| Trehalose metabolism | treB | PTS trehalose transporter subunit IIBC | 123354..124769 | GPJ58_19125 | 2.7.1.201 |

| treR | HTH-type transcriptional regulator TreR | 124907..125854 | GPJ58_19130 | ||

| lamB | maltoporin LamB | 45316..46608 | GPJ58_21525 | - |

Analyses of the genomes of these three endophytic bacteria revealed a set of drought resistance, heat shock and cold shock genes (Table 3A). Interestingly, the endophytes Serratia sp. HSTU-Abk35 were found to have enormous set of genes, including chaAB, proABQVWXPS, betAB, trkAH, kdbD, and kdpABCE, conferring drought resistance toward host plants (Table 3B). Moreover, a set of genes responsible for heavy metals such as arsenic, chromium, and cadmium bioremediation were annotated in the strain’s genome. The genomes shelter enormous number of genes whose products are responsible for pesticide degradation for instance ampD, glpABQ, pdeHR, pepABDE, phnFDGHKLMP., carboxylesterase family protein, amidohydrolase, amidohydrolase family protein, α/β-fold hydrolase, and paaC (Table 3C).

Table 3B. Genes associated with abiotic stress tolerance available in genome Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35.

| Activity description | Gene Name | Gene annotation | Chromosome location | Locus Tag

| E.C. number | |

| Cold Shock protein | cspE | transcription antiterminator/RNA stability regulator CspE | 300326..300535

| GPJ58_09795 | - | |

| cspD | cold shock-like protein CspD | 147230..147451 | GPJ58_03730 | - | ||

| Heat Shock protein | smpB | SsrA-binding protein SmpB | 201215..201697 | GPJ58_14210 | - | |

| hslR | ribosome-associated heat shock protein Hsp15 | 57973..58380 | GPJ58_17970 | |||

| ibpA | heat shock chaperone IbpA | 140535..140948 | GPJ58_17375 | - | ||

| ibpB | heat shock chaperone IbpB | 140000..140428 | GPJ58_17370 | - | ||

| hspQ | heat shock protein HspQ | 49462..49779 | GPJ58_03340 | - | ||

| groL | chaperonin GroEL | 47334..47627 | GPJ58_23035 | - | ||

| groES | Heat shock protein 60 family co-chaperone GroES | 47334..47627 | GPJ58_23030 | - | ||

| yegD | Putative heat shock protein YegD | 63748..65100 | GPJ58_13590 | |||

| dnaJ | molecular chaperone DnaJ | 187704..188828 | GPJ58_12600 | - | ||

| dnaK | molecular chaperone DnaK | 188935..190848 | GPJ58_12605 | - | ||

| djlA | co-chaperone DjlA | 154104..156464 | GPJ58_12450 | |||

| rpoH | RNA polymerase sigma factor RpoH | 46212..47069 | GPJ58_21905 | - | ||

| lepA | elongation factor 4 | 182995..184794 | GPJ58_14115 | 3.6.5.n1 | ||

| grpE | nucleotide exchange factor GrpE | 196309..196893 | GPJ58_14180 | - | ||

| Heavy metal resistance | ||||||

| arsB | arsenical efflux pump membrane protein ArsB | 238018..239307

| GPJ58_01040 | - | ||

| arsC | arsenate reductase (glutaredoxin) | 239322..239753 | GPJ58_01045 | 1.20.4.1 | ||

| acrR | ultidrug efflux transporter transcriptional repressor AcrR | 225916..226575 | GPJ58_09460 | - | ||

| acrD | Multidrug efflux RND transporter permease | 4110..7244 | GPJ58_13330 | - | ||

| trkA | Trk system potassium transporter TrkA | 7549..8925 | GPJ58_23795 | - | ||

| Magnesium transport | corA | magnesium/cobalt transporter CorA | 75701..76651 | GPJ58_22055 | - | |

| corC | CNNM family magnesium/cobalt transport protein CorC | 326702..327580 | GPJ58_09935 | - | ||

| cobA | uroporphyrinogen-III C-methyltransferase | 50984..52414 | GPJ58_12025 | 2.1.1.107 | ||

| Copper homeostasis | copA | copper-exporting P-type ATPase CopA | 255232..257943 | GPJ58_09585 | - | |

| copD | copper homeostasis membrane protein CopD | 347230..348102/94013..94894 | GPJ58_06400 | - | ||

| Zinc homeostasis | znuA | zinc ABC transporter substrate-binding protein ZnuA | 503654..504598 | GPJ58_02320 | - | |

| znuB | zinc ABC transporter permease subunit ZnuB | 502035..502820

| GPJ58_02310 | - | ||

| znuC | zinc ABC transporter ATP-binding protein ZnuC | 502817..503575 | GPJ58_02315 | - | ||

| Zinc, cadmium, lead and mercury homeostasis | ||||||

| Zinc homeostasis | adhP | alcohol dehydrogenase AdhP | 36440..37456 | GPJ58_10515 | 1.1.1.1 | |

| htpX | protease HtpX | 261841..262719 | GPJ58_07260 | 3.4.24.- | ||

| zntB | zinc transporter ZntB | 297515..298498 | GPJ58_11560 | - | ||

| Manganese homeostasis | mntR | manganese-binding transcriptional regulator MntR | 62165..62635 | GPJ58_06220 | - | |

| mntP | manganese efflux pump MntP | 451843..452412 | GPJ58_02070 | - | ||

| mntH | Mn(2+) uptake NRAMP transporter MntH | 62865..64169 | GPJ58_06225 | - | ||

| Drought resistance | nhaA | Na+/H+ antiporter NhaA | 186301..187467 | GPJ58_12595 | - | |

| chaA | sodium-potassium/proton antiporter ChaA | 366046..367149 | GPJ58_01655 | - | ||

| chaB | putative cation transport regulator ChaB | 368391..368618 | GPJ58_01665 | - | ||

| proA | glutamate-5-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | 57632..58891 | GPJ58_08605 | 1.2.1.41 | ||

| proB | glutamate 5-kinase | 56525..57628 | GPJ58_08600 | 2.7.2.11 | ||

| proQ | RNA chaperone ProQ | 252783..253493 | GPJ58_07220 | - | ||

| proV | glycine betaine/L-proline ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | 277704..278906

| GPJ58_14625 | - | ||

| proW | glycine betaine/L-proline ABC transporterpermease ProW | 278899..280005

| GPJ58_14630 | - | ||

| proX | glycine betaine/L-proline ABC transporter substrate-binding protein ProX | 280075..281076

| GPJ58_14635 | - | ||

| proP | glycine betaine/L-proline transporter ProP | 8027..9529 | GPJ58_05945 | - | ||

| proS | proline--tRNA ligase | 4908..6626 | GPJ58_22590 | 6.1.1.15 | ||

| betA | choline dehydrogenase | 341752..343419 | GPJ58_04620 | 1.1.99.1 | ||

| betB | betaine-aldehyde dehydrogenase | 343557..345029 | GPJ58_04625 | 1.2.1.8 | ||

| trkA | Trk system potassium transporter TrkA | 7549..8925 | GPJ58_23795 | - | ||

| trkH | Trk system potassium transporter TrkH | 656..2107 | GPJ58_21695 | - | ||

| kdbD | two-component system sensor histidine kinase KdbD | 357875..360571 | GPJ58_10090 | 2.7.13.3 | ||

| kdpA | potassium-transporting ATPase subunit KdpA | 363329..365017 | GPJ58_10105 | - | ||

| kdpB | potassium-transporting ATPase subunit KdpB | 361233..363302 | GPJ58_10100 | - | ||

| kdpC | potassium-transporting ATPase subunit KdpC | 360645..361214 | GPJ58_10095 | - | ||

| kdpE | /two-component system response regulator KdpE | 357169..357858 | GPJ58_10085 | - | ||

Table 3C. Genes associated with pesticide degradation available in genome Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35.

| Activity description | Gene Name | Gene annotation | Chromosome location | Locus Tag | E.C. number |

| ampD | 1,6-anhydro-N-acetylmuramyl-L-alanineamidase | 90916..91512 | GPJ58_12180 | 3.5.1.28 | |

| glpA | anaerobic glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase subunit | 64191..65840 | GPJ58_22005 | 1.1.5.3 | |

| glpB | glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase subunit | 62933..64201 | GPJ58_22000 | 1.1.5.3 | |

| glpQ | Glycerol phosphodiester phosphodiesterase | 67640..68719 | GPJ58_22015 | 3.1.4.46 | |

| Pesticide degrading | pepA | leucyl aminopeptidase | 148575..150086 | GPJ58_19220 | 3.4.11.1 |

| pepB | aminopeptidase PepB | 130560..131840 | GPJ58_13880 | 3.4.11.23 | |

| pepD | cytosol nonspecific dipeptidase | 52301..53761 | GPJ58_08580 | 3.4.13.18 | |

| pepE | -/dipeptidase PepE | 11487..12212 | GPJ58_21735 | 3.4.13.21 | |

| phnF | phosphonate metabolism transcriptional regulator PhnF | 111772..112497 | GPJ58_19070 | - | |

| phnD | phosphonate ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 460181..461113 | GPJ58_05210 | - | |

| phnG | phosphonate C-P lyase system protein PhnG | 111328..111771 | GPJ58_19065 | - | |

| phnH | phosphonate C-P lyase system protein PhnH | 110743..111324 | GPJ58_19060 | 2.7.8.37 | |

| phnK | phosphonate C-P lyase system protein PhnK | 108017..108805 | GPJ58_19045 | - | |

| phnL | phosphonate C-P lyase system protein PhnL | 107305..108000 | GPJ58_19040 | - | |

| phnM | lpha-D-ribose 1-methylphosphonate 5 triphosphatediphosphatase | 113413..114549/106169.107305 | GN159_10580/ GPJ58_19035 | 3.6.1.63 | |

| phnP | phosphonate metabolism protein PhnP | 104206..104988 | GPJ58_19020 | 3.1.4.55 | |

| pdeH | cyclic-guanylate-specific phosphodiesterase | 14132..14923 | GPJ58_23400 | - | |

| pdeR | cyclic di-GMP phosphodiesterase | 5241..7235 | GPJ58_23370 | 3.1.4.52 |

3.3. Model Quality of Pesticide-Degrading Proteins in Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35

The pesticide-degrading protein models for Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 were evaluated using a variety of parameters, as shown in Table 4. A total of 29 model proteins were generated using the template-based method in "I-TASSER". When assessing the quality of the protein models; TM score, RMSD, Identity (Iden.), Coverage (cov.), orientation of secondary structures (α-helix, β–strand, η–coil & disordered), "ERRAT" score (quality score based on non-bonded interactions of different types of atom), "VERIFY 3D" (verification of 3D representation according to refined structures from PDB) and Ramachandran plot (core, allowed, generously allowed and disallowed %) analyses were taken into account. The average TM score for the 29 models was 0.92, while the median was 0.93. Additionally, the most common values (mode) were 0.96, which is an indication of the excellent quality of the models. The mean, median, and mode values for all the quality parameters were calculated subsequently to get a general idea of the results found. The mean and median of the quality score in ERRAT came out as 79.35 and 84.01, RMSD came out as 0.61 and 0.61, identity came out as 0.52 and 0.49, coverage came out as 0.89 and 0.91, α–helix came out as 32.76 and 32.0, β–strand came out as 20.07 and 20.0, η–coil came out as 45.90 and 46.5, disordered came out as 7.21 and 3.5, VERIFY (3D-ID score) % came out as 82.28 and 83.44 and Ramachandran plot (core, allow, gener, disallow) % came out as 81.06, 15.34, 2.16, 1.45 and 82.3, 15.17, 1.75, 1.3 which are optimal while 3D-1D verification in "VERIFY3D". Notably 18 proteins that are VERIFY (3D-ID score) above 80% are green and 11 proteins that are VERIFY (3D-ID score) below 80% are purple.

Table 4. Model quality of pesticide degrading protein Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35.

| List | Model protein | Best PDB hit | TM score, RMSD, Identity, coverage | α -helix, β –strand, η-coil, disordered | ERRAT (quality score) | VERIFY (3D-ID score) % | Ramachandran plot (core, allow, gener, disallow) % |

| AmpD | 1j2s | 0.93, 0.49, 0.71, 0.94 | 24, 15, 60, 10 | 77.36 | 89.39 | 57.0, 35.8, 5.5, 1.8 | |

| glpA | 2rgo | 0.91, 0.54, 0.67, 0.88 | 35, 18, 46, 5 | 87.80 | 80.87 | 68.5, 22.1, 6.5, 2.9 | |

| GlpB | 1lpf | 0.87, 0.46, 0.65, 0.93 | 27, 19, 52, 0 | 70.53 | 87.68 | 55.2, 32.5, 7.5, 4.9 | |

| glpQ | 1ydy | 0.94, 0.43, 0.31, 0.91 | 32, 15, 52, 8 | 79.42 | 89.69 | 86.1, 12.0, 1.3, 0.6 | |

| OpdE | 6kki | 0.91, 0.48, 0.29, 0.91 | 80, 0, 19, 100 | 98.21 | 78.75 | 89.9, 7.7, 1.2, 1.2 | |

| pdeH | 4rnf | 0.93, 1.32, 0.18, 0.96 | 32, 18, 49, 12 | 88.23 | 70.34 | 85.9, 12.0, 1.7, 0.4 | |

| pdeR | 5xgb | 0.81, 0.64, 0.27, 0.81 | 40, 25, 34, 1 | 79.87 | 75.45 | 72.2, 19.9, 4.4, 3.5 | |

| pepA | 1gyt | 0.99, 0.23, 0.91, 1.00 | 33, 20, 46, 1 | 96.16 | 98.01 | 81.9, 15.5, 1.2, 1.4 | |

| PepB | 6cxd | 0.96, 0.30, 0.845, 0.97 | 34, 20, 44, 0 | 93.06 | 88.50 | 82.3, 15.0, 1.6, 1.1 | |

| pepD | 3mru | 0.84, 0.70, 0.55, 0.83 | 26, 25, 47, 3 | 85.44 | 96.08 | 83.4, 15.4, 1.0, 0.2 | |

| PepE | 1fye | 0.87, 0.61, 0.36, 0.91 | 28, 27, 43, 0 | 82.58 | 98.28 | 88.2, 7.9, 2.0, 2.0 | |

| phnF | 2wv0 | 0.86, 0.57, 0.44, 0.92 | 28, 33, 38, 4 | 97.41 | 75.52 | 79.2, 18.1, 2.3, 0.5 | |

| phnG | 4xb6 | 0.82, 0.65, 0.29, 0.86 | 43, 27, 29, 4 | 92.75 | 73.47 | 84.4, 13.3, 0.0, 2.3 | |

| PhnH | 2fsu | 0.84, 0.75, 0.53, 0.86 | 24, 21, 54, 3 | 95.67 | 90.16 | 74.4, 21.3, 1.8, 2.4 | |

| PhnI | 4xb6 | 0.96, 0.89, 0.78, 0.97 | 37, 13, 49, 11 | 89.27 | 54.85 | 78.8, 17.3, 2.3, 1.6 | |

| PhnJ | 4xb6 | 0.96, 0.27, 0.88, 0.96 | 24, 19, 56, 5 | 92.08 | 81.82 | 78.9, 17.5, 0.4, 3.3 | |

| PhnK | 4fwi | 0.95, 0.73, 0.30, 0.96 | 33, 20, 46, 5 | 93.30 | 93.51 | 82.1, 15.7, 1.3, 0.9 | |

| PhnL | 5gko | 0.92, 0.82, 0.32, 0.94 | 34, 25, 40, 2 | 91.03 | 87.88 | 80.0, 15.6, 2.9, 1.5 | |

| paaC | 1OTK | 0.94, 0.81, 0.58, 0.85 | 27, 24, 48, 4 | 92.11 | 94.38 | 93.6, 5.9, 0.0, 0.5 | |

| M-10 | 6I5S | 0.83, 0.62, 0.41, 0.73 | 31, 17, 50, 12 | 38.15 | 69.43 | 75.6, 19.2, 3.6, 1.5 | |

| M-9 | 2ICS | 0.72, 0.68, 0.75, 0.81 | 27, 24, 48, 4 | 81.14 | 95.45 | 90.7, 8.6, 0.3, 0.3 | |

| M-8 | 4DO7 | 0.91, 0.59, 0.73, 0.89 | 37, 14, 48, 3 | 89.78 | 99.65 | 88.5, 10.3, 0.4, 0.8 | |

| M-7 | 4EWT | 0.95, 0.76, 0.31, 0.79 | 35, 23, 41, 0 | 75.13 | 83.68 | 89.5, 9.3, 0.9, 0.3 | |

| M-6 | 2ODF | 0.84, 0.64, 0.41, 0.81 | 30, 15, 53, 6 | 78.60 | 85.66 | 89.5, 9.6, 1.0, 0.0 | |

| M-5 | 5XOY | 0.99, 0.54, 0.81, 1.00 | 31, 22, 45, 3 | 52.81 | 66.49 | 82.4, 13.7, 3.0, 0.9 | |

| M-4 | 2E11 | 0.96, 0.35, 0.84, 0.93 | 21, 33, 45, 1 | 77.82 | 83.20 | 89.2, 9.9, 0.9, 0.0 | |

| M-3 | 2QYV | 0.86, 0.78, 0.45, 0.83 | 34, 23, 42, 1 | 44.00 | 71.74 | 76.3, 18.1, 2.5, 3.1 | |

| M-2 | 1M22 | 0.77, 0.69, 0.36, 0.96 | 35, 11, 53, 1 | 56.31 | 79.53 | 84.8, 12.7, 2.3, 0.3 | |

| M-1 | 2FTY | 0.96, 0.27, 0.34, 0.81 | 28, 16, 54, 0 | 25.27 | 46.80 | 82.3, 13.1, 2.8, 1.8 |

*[M-1= amidohydrolase family protein (locus_tag="GPJ58_05060), M-2= AtzE family amidohydrolase (locus_tag="GPJ58_08375) M-3= allantoate amidohydrolase (locus_tag="GPJ58_08420), M-4= amidohydrolase (locus_tag="GPJ58_08425), M-5= amidohydrolase (locus_tag="GPJ58_09790), M-6= N-formylglutamate amidohydrolase (locus_tag="GPJ58_11345), M-7= amidohydrolase (locus_tag="GPJ58_11730), M-8= amidohydrolase family protein (locus_tag="GPJ58_12900), M-9= amidohydrolase/deacetylase family metallohydrolase (locus_tag="GPJ58_14960), M-10= amidohydrolase family protein (locus_tag="GPJ58_17120) ]

3.4. Virtual screening and box plot of complex

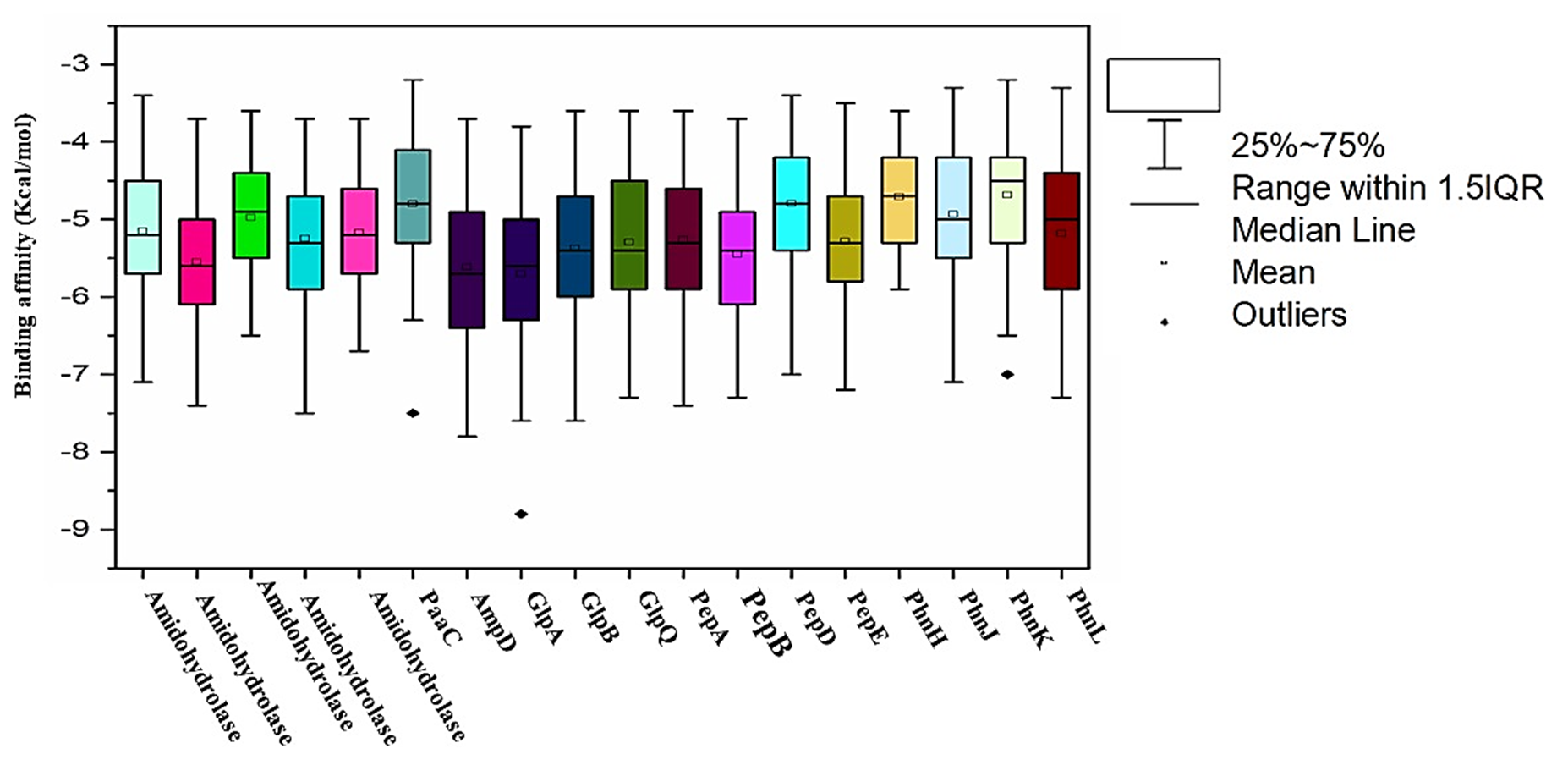

The virtual screening of the selected eighteen model proteins of Serratia sp. strain HSTU-ABK35, with ninety-nine different pesticides, shown binding score ranges from -9 Kcal/mol to -3 Kcal/mol (Figure 3). It is shown that most of the binding scores are occupied between the 1st and 3rd quartile in the box plot (Figure 3), where the lower and upper quartile designates the 1st and 3rd quartile scores. Interestingly, three model proteins (PaaC, GlpA, PhnK) of Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35, and two model proteins (AmpD, PepA) binding score were placed outlier data points. The virtual screening results also showed that the binding affinity of many pesticide ligands crossed over to -6.5~8.0 Kcal/mol for organophosphate degrading potential proteins (Amidohydrolase variants, PaaC, AmpD, GlpA, GlpB, GlpQ, and various Pep and Phn proteins) from Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. virtual screening analysis of ninety-nine pesticides with pesticide degrading model proteins of Serratia sp. Strain HSTU-Abk35.

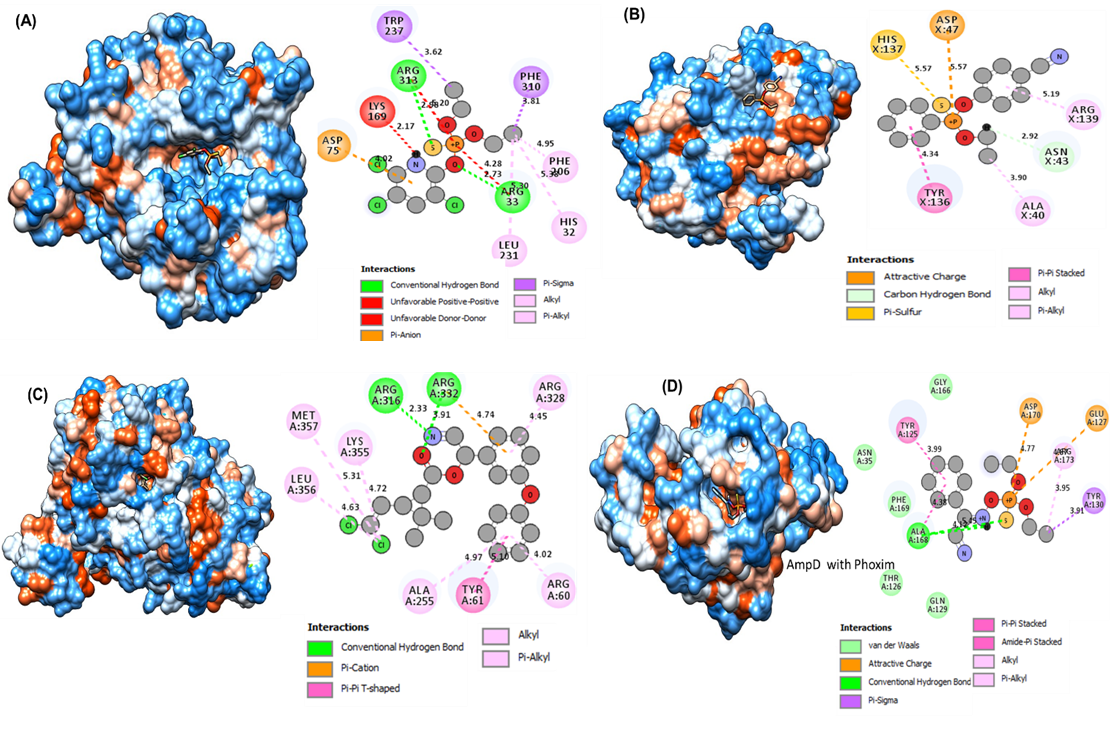

3.5. Molecular docking of top four selected protein-pesticide complex

In this circumstance, all the ligand molecules are observed to follow Lipinski’s rule of five (molecular weight not more than 500 Da; hydrogen bond donor not more than 5; hydrogen bond acceptors not more than 10; log p-value not greater than 5). The 2D and 3D interactions of the four selected ligands with four proteins after docking show the active sites of the receptor were visualized by using biovia discovery studio and chimera. The 2D and 3D catalytic interactions of the selected two proteins catalytically important residues according to docking analyses are placed within 1.5–5.5Å that might play a role in the degradation of organophosphate pesticides. The GlpQ protein with a Chlorpyrifos docked complex demonstrated the interaction with multiple residues (Figure 4A). In particular, conventional H-bonds were made by the Arg33 and Arg313 to the benzene ring attached, S-atom. Besides, Asp75 formed π anion, Leu 231 formed an alkyl, Phe310 and Trp237 formed π-sigma, Phe306 and His32 formed π-alkyl Halogen interacted with chlorpyrifos' Cl-atom and benzene ring. Interestingly, this dock was formed by the catalytic tired His32-Arg33-Asp75.

PaaC interacts with Cayanophenophos via multiple amino acid residues (Figure 4B). In fact, the O-atom in the phosphodister bond of Cayanophenophos is attacked by Asp47 via attractive charge interaction with the phosphate atom. Notably, the His137 and His137 residues provided combined, π-sulfur and carbon hydrogen bond interactions to the Cypermethrin compound, respectively. Attractively, this interacted to form a catalytic tire, His137-Arg139-Asp47.

Likewise, the GlpA with Cypermethrin docked complex showed multiple residue interactions (Figure 4C). The conventional hydrogen bond interaction was observed for Arg316 and Arg332 with the side chain of the benzene ring attached, the O-atom, and the N-H atom of the phosphodiester of Azinophos ethyl compound, while Lys355, Leu356, and Met356 formed alkyl and π-alkyl bonds with the Cl-atom of Azinophos ethyl, and Tyr61 formed.

The AmpD protein and Phoxim insecticide docked complex ligand interactions were observed by the different residues (Figure 4D). In particular, Glu127 with Asp170 provided an attractive charge interaction with the phosphate atom. The interaction distance was 4.77 and 4.87. In addition, conventional hydrogen bond and pi sigma interactions were observed with the Ala168 and Arg173 residues. The interaction distances among the residues of the catalytic site were recorded within <3.9 Å.

Figure 4. (A) Molecular docking and chemicals interactions of organophosphorus degrading model protein GlpQ of Serratia sp. Strain HSTU-Abk35 with chlorpyrifos pesticides. (B) Molecular docking and chemicals interactions of organophosphorus degrading model protein PaaC of Serratia sp. Strain HSTU-Abk35 with Cayanophenophos pesticides. (C) Molecular docking and chemicals interactions of organophosphorus degrading model protein GlpA of Serratia sp. Strain HSTU-Abk35 with Cypermethrin pesticides. (D) Molecular docking and chemicals interactions of organophosphorus degrading model protein AmpD of Serratia sp. strain HSTU-Abk35 with phoxim pesticides.

The comprehensive genomic and functional characterization of Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 reveals this strain as an ecologically versatile endophyte capable of simultaneously promoting plant health and degrading multiple classes of pesticides. The integration of whole-genome sequencing, phylogenomic analyses, gene repertoire profiling, structural modeling, and molecular docking establishes a robust framework for understanding its dual ecological and biotechnological significance. Such multi-layer genome-to-function approaches have been emphasized in recent studies exploring plant-associated bacteria with environmental or agricultural relevance [4, 2].

Genome-based phylogenetic analyses clearly placed Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35within the Serratia marcescens species complex, supported by high ANI and dDDH values consistent with species-level boundaries defined by Meier-Kolthoff et al. [27]. The clustering of housekeeping genes such as recA and rpoB with reference S. marcescens strains agrees with previous findings demonstrating the utility of these loci for fine-scale taxonomic discrimination within Serratia [11]. The subtle divergence observed in the gyrB-based clustering suggests microevolutionary adaptation, a pattern previously documented in Serratia strains exposed to environmental stressors or agrochemicals. Such genomic plasticity is often associated with niche adaptation among endophytes colonizing plant tissues [29].

Pan-genome comparison and locally collinear block analysis revealed several strain-specific genomic regions in Serratia sp. strain HSTU-ABk35, indicating acquisition of novel operons potentially through horizontal gene transfer. This aligns with reports of diverse Serratia lineages evolving specialized genetic modules for metabolic versatility in soil and plant-associated environments [30]. The presence of unique genomic islands containing xenobiotic-degradation and colonization-related genes parallels the genomic signatures observed in Serratia plymuthica, S. nematodiphila, and other environmental strains enriched for ecological adaptability [30]. Similar patterns of metabolic specialization have been described in endophytes and gut-associated bacteria such as Klebsiella variicola, where strains display niche-driven acquisition of lignocellulolytic and catabolic functions [17].

The plant-beneficial genetic repertoire of Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35includes genes associated with nitrogen metabolism, siderophore biosynthesis, ACC deaminase, phytohormone pathways, and stress response systems—traits widely reported to contribute to plant growth promotion and enhanced stress tolerance [2, 4, 31]. These functions resemble those of well-characterized endophytic Serratia strains that enhance crop growth, nutrient uptake, and systemic resistance [12, 32]. Genes associated with induced systemic resistance reflect mechanisms previously described for beneficial plant–microbe interactions mediated by microbial metabolites and volatiles [33]. The presence of multiple oxidative, osmotic, and heavy-metal stress tolerance operons further underscores the strain’s ecological resilience, consistent with bacterial adaptation strategies reported under agricultural stress conditions [34].

One of the most notable characteristics of Serratia sp. strain HSTU-ABk35 is its large and diverse array of xenobiotic-degrading genes, including carboxylesterases, α/β-hydrolases, amidohydrolases, phosphonate-metabolizing operons, and enzymes associated with aromatic compound breakdown. These gene families are well known for their roles in the degradation of organophosphate, organochlorine, and pyrethroid pesticides [35-38].

The presence of ampD, glpA, glpB, glpQ, and pep operons resembles enzymatic systems reported to mineralize chlorpyrifos, diazinon, methyl parathion, cypermethrin, and other toxic agrochemicals [3, 4]. The degradative capacities inferred here are also consistent with recent studies discovering novel pesticide-hydrolyzing esterases from rumen metagenomes [23] and biodegradation traits present in lactic acid bacteria and related taxa [36]. The genetic convergence between HSTU-ABk35 and other pesticide-mineralizing endophytes demonstrates clear evolutionary pathways for adapting to agrochemical-intensive environments [1].

This study leveraged a comprehensive computational approach to identify and characterize putative pesticide-degrading enzymes from Serratia sp. strain HSTU-ABk35. The findings offer significant insights into the structural characteristics and interaction mechanisms of these bacterial proteins with various agricultural pesticides. The initial phase involved the prediction of three-dimensional enzyme structures through homology modeling, followed by rigorous validation. The consistently high quality of the models-confirmed by excellent ERRAT and VERIFY-3D scores and favorable Ramachandran plot analyses-established a robust foundation for subsequent computational investigations [25, 3, 37]. This rigorous validation ensures the structural reliability necessary for accurate predictions of enzyme-substrate interactions. Virtual screening revealed a broad capacity among the identified enzymes to bind pesticide compounds. Notably, many proteins with organophosphate-degrading potential across all three bacterial strains, including amidohydrolase variants, PaaC, AmpD, Glp, and Pep/Phn proteins, exhibited strong binding affinities, frequently falling within the -6.5 to -8.0 Kcal/mol range. The identification of outlier interactions further points to exceptionally strong and specific binding events for certain protein-pesticide pairs [3, 4, 32, 37, 38]. This widespread and potent binding capability highlights these bacterial enzymes as promising candidates for pesticide recognition and detoxification. Detailed molecular docking provided atomic-level insights into these crucial interactions. Analysis elucidated specific amino acid residues involved in stabilizing the protein-pesticide complexes through various bond types, such as conventional hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and pi-interactions. A particularly noteworthy finding was the identification of potential catalytic triads within the binding pockets. These specific arrangements of amino acids are characteristic of enzymatic active sites and play a critical role in facilitating chemical catalysis, strongly suggesting an active degradative function for these proteins.

In conclusion, this genomic and computational investigation provides a comprehensive characterization of pesticide-degrading protein models from the endophytic bacteria. The robust models, strong pesticide binding affinities, and the identification of potential catalytic sites collectively underscore the significant potential of these enzymes as novel biocatalysts for environmental bioremediation.

The genomic and functional characterization of Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 underscores its status as a novel endophytic strain within the Serratia marcescens complex, exhibiting measurable evolutionary divergence from known reference strains. The strain harbors a comprehensive repertoire of plant growth-promoting genes, including those for phytohormone production, nutrient mobilization, stress tolerance, and induction of systemic resistance, suggesting its robust potential to enhance crop health under variable environmental conditions. In parallel, the presence of a diverse suite of xenobiotic-degrading genes, combined with in silico validation of enzyme–pesticide interactions, indicates its capacity to biotransform multiple classes of pesticides. These dual functionalities position Serratia sp. HSTU-ABk35 as a promising candidate for microbial inoculants aimed at sustainable agriculture, offering both enhancement of plant productivity and mitigation of agrochemical residues. Future experimental studies, including greenhouse and field trials, are warranted to validate its agricultural performance and bioremediation efficacy.

The authors gratefully acknowledge IRT of Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University (HSTU), for financial support. We also thank all contributors for their valuable roles in the preparation of this manuscript. This study addresses about 10% AI-assisted text following the journal policy.

This research was supported by the grants from the Institute of Research and Training (IRT)-Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University (HSTU) in fiscal year 2021-2022 at Dinajpur, Bangladesh.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This study did not involve any experiments on human participants or animals; therefore, formal written informed consent was not required by the Institutional Review Board. All figures in this study were created; therefore, no permission for reuse is required for any figure presented herein.

The assembled and annotated genome sequence of Serratia sp. strain HSTU-ABk35, isolated from rice plant roots, was deposited in the NCBI database under the accession number WSPF00000000, with BioSample SAMN13520210 and BioProject PRJNA594520.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

.

You are free to share and adapt this material for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit.