J. Biosci. Public Health. 2026; 2(1)

Endophytic bacteria with combined plant growth-promoting (PGP) and pesticide biodegradation capacities offer sustainable agroecosystem management. This study reports the isolation, biochemical characterization, whole-genome sequencing, and in silico functional analysis of an endophytic bacterium, Acinetobacter sp. strain HSTU-Asm16, isolated from rice (Oryza sativa L.). Biochemical assays show catalase, oxidase, and citrate utilization; carbohydrate fermentation; and a suite of extracellular hydrolases consistent with plant-associated metabolism. The draft genome (~3.94 Mb) was annotated using the NCBI PGAP pipeline and analyzed for phylogenetic placement, including phylogenomics, average nucleotide identity (ANI), digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH), pangenome assessment, and synteny analysis. Genome taxonomy placed HSTU-Asm16 within the Acinetobacter soli clade, confirming its status as a genomically distinct strain rather than a novel species. The identified genes are used in plant growth promotion (IAA, siderophore biosynthesis, ACC deaminase, and phosphate metabolism), stress tolerance (heat-/cold-shock proteins and heavy-metal resistance), and a complement of putative organophosphate-degrading enzymes (carboxylesterases, phosphotriesterases, amidohydrolases, and opd-like sequences). The genome encodes nif-associated and isc-related iron-sulfur cluster assembly genes, including nifS, nifU, iscU, and iscA, are involved in Fe–S protein maturation rather than canonical nitrogen fixation. Molecular docking with representative organophosphate ligands showed plausible substrate active site interactions for several hydrolases. The biochemical, genomic, and in silico evidence indicates Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 is a promising plant-associated bacterium with dual potential for plant growth promotion and organophosphate pesticide bioremediation in rice farming.

Pesticide contamination has become a critical environmental and public health concern worldwide, driven by the extensive and often indiscriminate use of agrochemicals in modern agriculture. Persistent pesticide residues accumulate in soil, water, and food chains, posing serious ecological risks and long-term health hazards to both humans and wildlife [1, 2]. These challenges underscore the urgent need for sustainable and efficient remediation strategies capable of detoxifying contaminated agricultural environments. Among the emerging solutions, microbial bioremediation-particularly using plant-associated bacteria offers a promising, eco-friendly alternative for degrading hazardous agrochemical residues. Endophytic bacteria, which inhabit the internal tissues of plants without causing harm, have attracted considerable attention for their unique capacity to degrade a wide variety of organic pollutants, including pesticides, within both plant hosts and the surrounding rhizosphere [3, 4]. Their intimate association with plants allows them to complement phytoremediation by enhancing nutrient acquisition, producing growth-promoting hormones, and secreting enzymes that play central roles in the degradation and transformation of xenobiotics. These beneficial traits collectively contribute to improved plant vigor and more efficient removal of contaminants from the environment.

Within the diverse community of endophytes, Acinetobacter species have emerged as particularly significant contributors to pesticide bioremediation. Several Acinetobacter strains have been reported to degrade organophosphorus pesticides such as chlorpyrifos, diazinon, and acetamiprid, often functioning as key members of microbial consortia involved in pollutant breakdown [5-7]. Their enzymatic repertoire includes esterases, organophosphorus hydrolases, amidohydrolases, carboxylesterases, and phosphotriesterases, which catalyze the detoxification of diverse pesticide molecules. Notably, enzymes such as molinate hydrolase from Gulosibacter molinativorax illustrate the specificity and efficiency with which microbial enzymes can degrade thiocarbamate herbicides [8], demonstrating the broader catalytic potential of pesticide-degrading bacteria.

Beyond their biodegradation abilities, Acinetobacter species also contribute significantly to plant growth promotion and nutrient cycling. Some strains, such as Acinetobacter guillouiae, demonstrate nitrogen-fixing capabilities that enhance crop growth when used as co-inoculants [9]. Others play key roles in biological nitrogen fixation in crops like sugarcane [10]. Although nitrogen fixation genes such as nifA may be present in some genomes, the complete nitrogenase gene cluster is not universal among all strains [11]. Nonetheless, several Acinetobacter species including Acinetobacter sp. Y16, A. junii, and A. kyonggiensis are known for heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification, contributing to nitrogen removal even under low temperatures [12-15]. Phosphate solubilization is another key plant growth-promoting trait widely observed among Acinetobacter species. Strains such as Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, A. pittii gp-1, and Acinetobacter sp. RSC7 can transform insoluble phosphorus into bioavailable forms, thereby supporting nutrient uptake in plants [16-18]. Some isolates, including those from karst rocky desertification areas, demonstrate sustained solubilization efficiency under nutrient-limited conditions [19]. Additionally, the ability of Acinetobacter species to store polyphosphate [20] supports their metabolic versatility and environmental adaptability. Acinetobacter sp. endophytes also influence plant growth through the production of phytohormones such as indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), with strains like Acinetobacter sp. PUCM1007 and A. baumannii PUCM1029 producing significant levels of this hormone [16]. Siderophore production, another hallmark of Acinetobacter species, enhances iron acquisition and can suppress phytopathogens. Siderophores such as acinetobactin and fimsbactin not only support microbial survival but also promote plant health by limiting pathogen access to iron [21, 22]. Although direct evidence for ACC-deaminase activity in Acinetobacter remains limited, these species are well-documented contributors to plant stress tolerance, as shown in Acinetobacter johnsonii enhancing resilience in Populus deltoides under adverse conditions [23]. In recent years, in silico approaches have become indispensable for elucidating the mechanisms underlying microbial pesticide degradation. Virtual screening, molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and homology modeling allow researchers to investigate enzyme–substrate interactions, predict catalytic sites, and assess protein efficiency at a molecular level [24-27].

Considering the previous research outcomes and limitations so far, the present study aims to investigate the bioremediation and plant growth-promoting potential of Acinetobacter sp. endophytes through integrated microbiological and computational approaches. By combining genomic, biochemical, and in silico analyses, this research seeks to advance the development of sustainable microbial solutions for pesticide detoxification and improved crop productivity.

2.1. Isolation and biochemical characterization

Endophytic Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 was isolated from surface-sterilized leaves of healthy Oryza sativa L. using standard isolation procedures described previously [5, 7, 28]. The sterilized tissues were macerated and plated onto minimal salt agar supplemented with 1.0% diazinon to selectively enrich pesticide-tolerant endophytes. Distinct colonies were purified and subjected to biochemical identification following the criteria outlined in Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (1996), including catalase, oxidase, citrate utilization, urease, and triple sugar iron assays [29]. In addition, hydrolytic capabilities such as cellulase, xylanase, and pectinase production were evaluated based on halo formation around colonies on respective substrate-amended agar media [30].

2.2. Genomic DNA extraction, sequencing, assembly, and annotation of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16

Genomic DNA of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 was extracted using the Promega Genomic DNA Extraction Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentration and purity were determined with a Promega spectrophotometer. Whole-genome shotgun sequencing was performed on the Illumina MiniSeq platform using paired-end chemistry. Library preparation from purified DNA employed the Nextera XT Library Preparation Kit according to standard protocols [31]. The quality of raw reads was evaluated with FASTQC version (v0.11.9), followed by adapter removal, quality trimming, and length filtering using the FASTQ Toolkit and assembled de novo with SPAdes v3.9.0. Resulting contigs were scaffolded, refined, and genome alignments were generated using Progressive Mauve v2.4.0 [32]. Genome assembly quality was assessed using SPAdes v3.9.0, and assembly metrics including total contigs, N50, genome size, GC content, and coverage were calculated using QUAST v5.2.0.

Genome annotation was conducted using both the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP v4.5) [33, 34]. Functional categorization of coding sequences was carried out using the COG database via the RAST annotation server, complemented by PGAP-derived annotations [35]. Multilocus sequence typing was performed, aligning with established methods for bacterial typing using whole-genome sequencing data [36]. Phylogenetic analyses based on the housekeeping genes recA,gyrB, and rpoB were performed in MEGA XI with 1,000 bootstrap replicates [29]. Genes associated with nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, phytohormone production, biofilm development, and abiotic stress responses were identified [33, 37, 38].

2.3. Comparative genomic and functional analyses

2.3.1. Phylogenetic and average nucleotide identity analysis

Housekeeping genes, including rpoB, recA, and gyrB, were extracted from the annotated genome of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16. Each gene was aligned individually, followed by concatenation for phylogenetic reconstruction. Neighbor-joining trees based on both the 16S rRNA gene and concatenated markers were generated using MEGA X. Whole-genome phylogenetic relationships were inferred using REALPHY 1.12 (http://www.realphy.unibas.ch /realphy/) by incorporating the genome of the target strain alongside its closest relatives. Average nucleotide identity (ANIb) between Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 and related taxa was calculated using the JSpeciesWS platform (http://jspecies.ribhost.com/jspeciesws) [29, 33]

2.3.2. Digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH)

Genome-level similarity was further assessed via digital DNA–DNA hybridization using the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC 3.0; https://ggdc.dsmz.de/). dDDH values were determined following standard formulas, comparing the target strain with fourteen phylogenetically related Acinetobacter genomes.

2.3.3. Genome alignment and synteny analysis

Whole-genome alignment of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 was performed using the MAUVE algorithm to visualize syntenic regions and structural variations. Colored blocks representing synteny facilitated the comparison of genomic architecture. Pangenome analysis was conducted using publicly available servers as described by [5] to examine gene distribution patterns across related species.

2.3.4. Genome-level comparison

To investigate genomic features, the draft genome of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 was compared with recently reported, closely related genomes. Circular and linear genome maps were generated using CGView (http://www.cgview) and BRIG v0.95, respectively. Sequence similarity was assessed via BLAST+ with identity thresholds of 70–90% and an E-value cutoff of 10. Genome collinearity and synteny were further examined using Progressive Mauve (http://darlinglab.org/mauve/mauve.html). Additionally, in-silico DNA–DNA hybridization was performed with the fifteen nearest genomes using the GGDC server.

2.4. Functional Gene Annotation: Plant growth promotion, stress tolerance, and insecticide degradation

Genes associated with plant growth–promoting (PGP) traits were mined from PGAP-annotated genome assemblies and compared with genomes of representative endophytic reference strains. Key functional categories identified included nitrogen metabolism–related genes (nifS–nifU and Fe–S cluster assembly genes iscA, iscU, and iscR, rather than complete nifA–nifZ clusters), nitrosative stress response and nitrogen regulation genes (norRV, ntrB, glnK, and nsrR), ammonia assimilation–associated genes, ACC deaminase–related enzymes, siderophore biosynthesis genes associated with enterobactin production, tryptophan-dependent indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) biosynthesis–related genes, and genes involved in phosphate and sulfur metabolism. Additional PGP-associated functional categories included biofilm formation and adhesion, chemotaxis and root colonization, trehalose metabolism, antioxidant defense systems (e.g., superoxide dismutase), diverse hydrolase-encoding genes, and genes linked to symbiosis-related pathways and antimicrobial peptide biosynthesis. Genes associated with abiotic stress tolerance, including cold-shock proteins, heat-shock proteins, drought/osmotic stress–responsive genes, and heavy metal resistance determinants, were also catalogued. Furthermore, genes putatively involved in organophosphate metabolism were identified based on functional annotation and homology to previously reported enzymes, including carboxylesterases, putative organophosphorus hydrolases (opd-like), amidohydrolases, phosphonatases, phosphotriesterases, and phosphodiesterases, in accordance with prior literature reports [39, 40].

2.5. Virtual screening and catalytic triad visualization

The 3D structures of the organophosphate insecticides investigated were obtained from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and organized for virtual screening. Prior to docking, the ligand molecules were subjected to geometry optimization and energy minimization using the MMFF94 force field with the steepest-descent method. Virtual screening was carried out in PyRx, where each ligand was individually docked with the selected protein targets. Multiple docking simulations were performed per enzyme to assess potential interactions within the active site and to confirm consistent binding patterns. Binding energies (kcal/mol) were extracted and visualized using R software. Enzymes with docking energies stronger than –7 kcal/mol were analyzed further, and detailed visualizations of key catalytic motifs, such as Ser-His-Asp and Ser-His-His triads, were generated to infer possible enzymatic mechanisms for insecticide degradation [24, 29].

2.6. Pesticides degrading protein modeling and docking with pesticides

Candidate pesticide-degrading enzymes were predicted and modeled using SWISS-MODEL and I-TASSER [37]. The structural integrity and reliability of the predicted models were assessed using ERRAT, VERIFY3D, and Ramachandran plot evaluation. Docking simulations conducted through PyRx and Discovery Studio revealed strong ligand–protein interactions, with binding energies ranging between –6.5 and –8.0 kcal·mol⁻¹, and highlighted critical catalytic residues implicated in organophosphorus pesticides degradation [34, 38].

3.1. Biochemical characterization of the newly isolated endophytic bacteria

Table 1 depict the biochemical characteristics of the three newly isolated bacterial strain Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 sourced from rice plants. The strains showed positive reactions for oxidase, citrate utilization, and catalase (Table 1). While Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 showed positive motility for both indole and urease tests. In the Methyl red test, Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 was positive, conversely, the strains exhibited opposite result patterns in the Voges Proskauer test (Table 1). Interestingly, the strain showed positive activity for both the TSI test and the carbohydrate (lactose, sucrose, dextrose) utilization test. Additionally, the strain was negative for the indole test but positive for the urease test. While cell wall hydrolytic enzymes activities, including xylanase, amylase, and protease were found in the strain, but CMCase activity was absent in the Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 (Table 1).

Table 1. Biochemical analyses of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16.

| Oxidase | Citrate | Catalase | MIU | Mortality | Urease | VP | MR | TSI | Lactose | Sucrose | Dextrose | CMCase | Xylanase | Amylase | Protease | |

| Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 | + | + | + | - | + | + | - | + | + | +

| + | + | - | + | + | + |

3.2. Genome organization and coding sequence (CDS) distribution

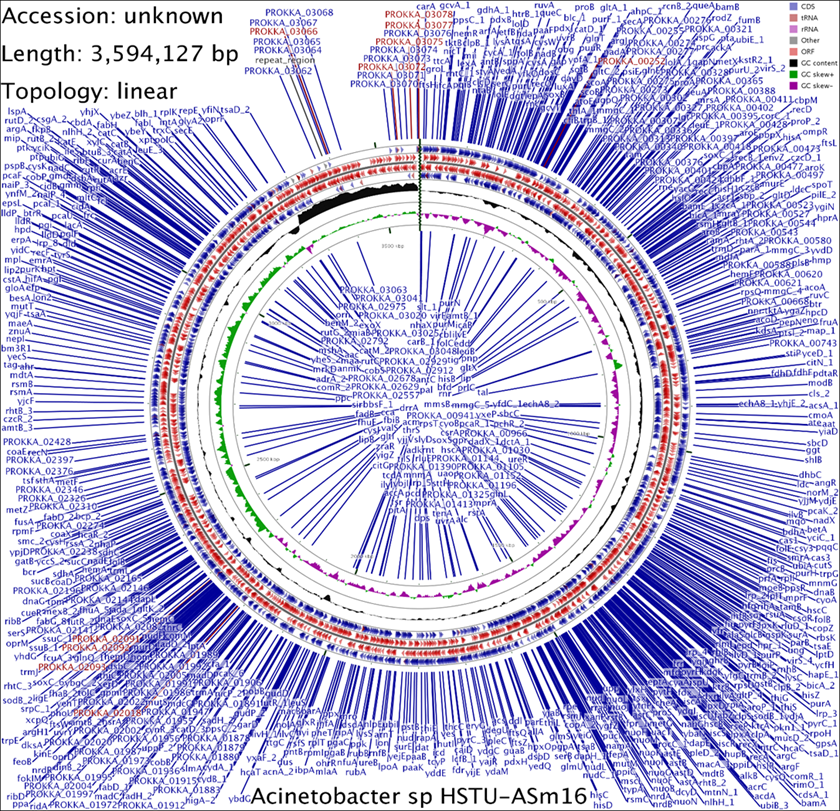

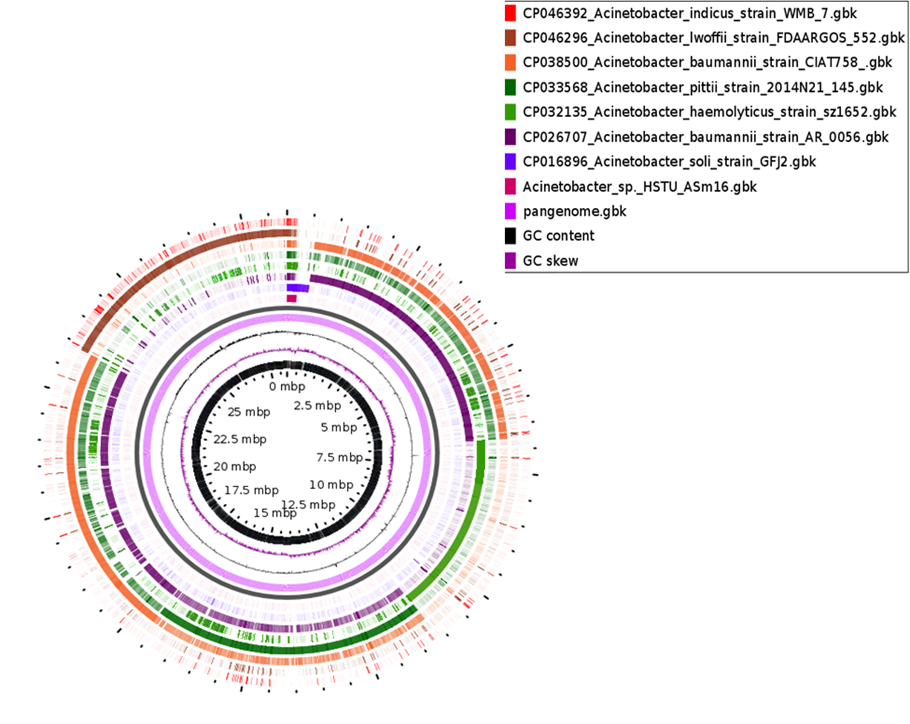

The complete genome map of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 is shown as a circular representation (Figure 1), with a total genome size of 3,594,127 bp and a linear topology. Genome annotation identified a dense and evenly distributed set of coding DNA sequences (CDSs) across the chromosome. The outermost rings represent annotated CDSs encoded on the forward and reverse strands, illustrated by directional arrows that indicate gene orientation. CDSs are distributed throughout the genome without large gene-poor regions, indicating a compact genomic architecture. Genes annotated as protein-coding sequences constitute the majority of features, with additional tracks representing tRNA and rRNA loci, which are interspersed across the chromosome. Inner rings depict GC content and GC skew variation along the genome. GC content shows moderate fluctuation around the genomic average, while GC skew alternates regularly between positive and negative values, consistent with bidirectional DNA replication from a putative origin toward the terminus. Distinct transitions in GC skew are visible, corresponding to replication-related structural features of the chromosome. The innermost ring displays the genomic coordinate scale, highlighting the relative positions of CDSs and structural features along the chromosome. No large-scale chromosomal rearrangements or extensive low-complexity regions were observed in the assembled genome.

Figure 1. Circular genome map of Acinetobacter sp. strain HSTU-Asm16. The draft genome (3,594,127 bp) is shown in circular form. From outer to inner rings: protein-coding sequences on the forward strand (blue) and reverse strand (red), tRNA genes (pink), rRNA genes (purple), followed by GC content (black) and GC skew (green and purple). Selected gene labels illustrate the compact and evenly distributed genomic organization.

3.3. Phylogenetic taxonomy of the endophytic bacteria

3.3.1. Whole genome phylogenetic analysis

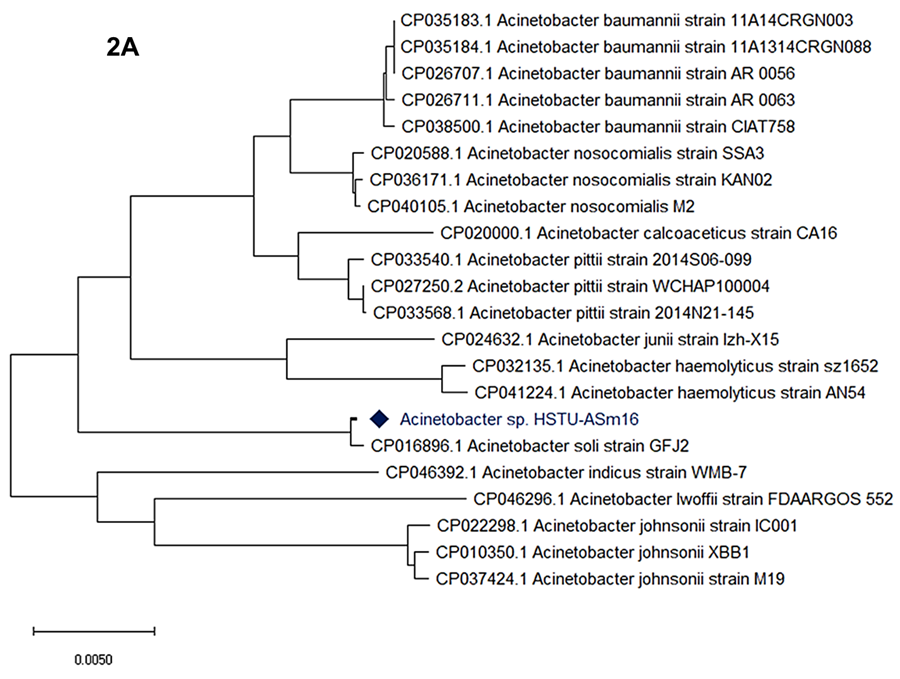

A whole-genome based phylogenetic tree was constructed to determine the evolutionary placement of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 among representative species of the genus Acinetobacter (Figure 2A). The analysis included multiple reference genomes from closely related species, including A. baumannii, A. pittii, A. calcoaceticus, A. nosocomialis, A. haemolyticus, A. junii, A. johnsonii, A. lwoffii, A. indicus, and A. soli. In the resulting phylogeny, Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 clustered most closely with Acinetobacter soli strain GFJ2, forming a distinct and well-supported lineage separate from other Acinetobacter species. This cluster was clearly resolved from the clades comprising clinically relevant A. baumannii strains, which grouped together in a separate, well-defined branch.

Additional species-level groupings were observed, including distinct clusters for A. pittii, A. nosocomialis, A. calcoaceticus, A. haemolyticus, and A. johnsonii, each forming coherent lineages consistent with their taxonomic assignments. Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 did not cluster within any of these species-specific clades other than A. soli. Overall, the whole-genome phylogenetic analysis places Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 within the A. soli related lineage, while maintaining clear separation from other closely related Acinetobacter species included in the analysis.

Figure 2. (A) Whole genome phylogenetic tree of the strain Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16.

3.3.2. Housekeeping genes phylogeny analysis

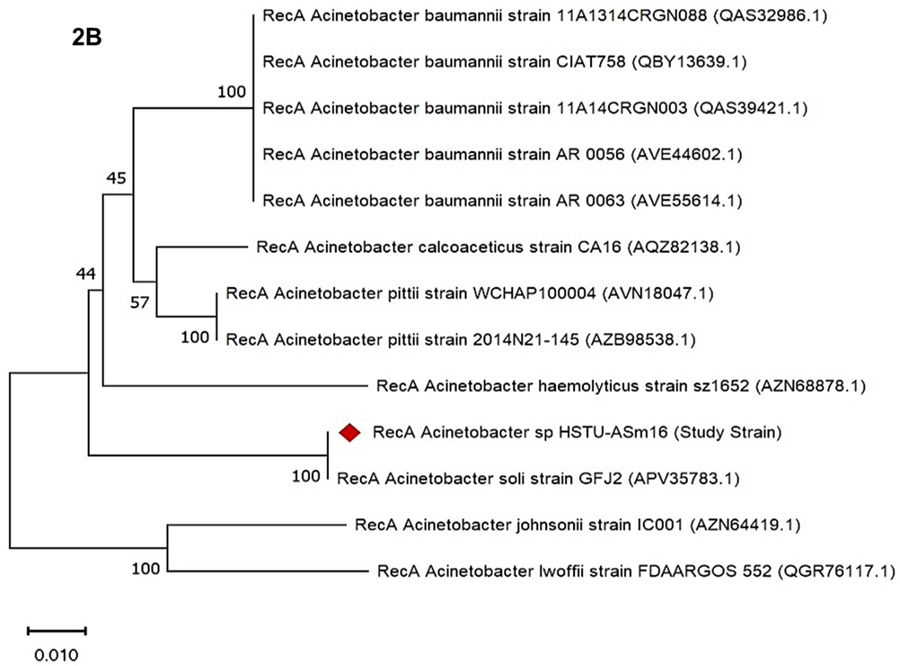

The phylogenetic tree based on the recA housekeeping gene was constructed to determine the evolutionary relationship of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 with closely related Acinetobacter species. The analysis revealed that HSTU-ASm16 clustered closely with Acinetobacter soli strain GFJ2, forming a distinct clade with a high bootstrap value of 100, indicating strong phylogenetic relatedness (Figure 2B). Other Acinetobacter species formed separate, well-supported clusters: A. baumannii strains (11A1314CRGN088, CIAT758, 11A14CRGN003, AR 0056, AR 0063) grouped together with a bootstrap value of 100, reflecting close intra-species relationships, while A. pittii strains (WCHAP100004 and 2014N21-145) also clustered with 100% bootstrap support. In contrast, A. calcoaceticus, A. haemolyticus, A. johnsonii, and A. lwoffii each formed separate branches, highlighting their genetic divergence from the study strain. Overall, the recA-based phylogeny indicates that Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 is most closely related to A. soli, supporting its classification as a distinct species within the genus.

Figure 2B. recA gene phylogenetic tree of the strain Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16.

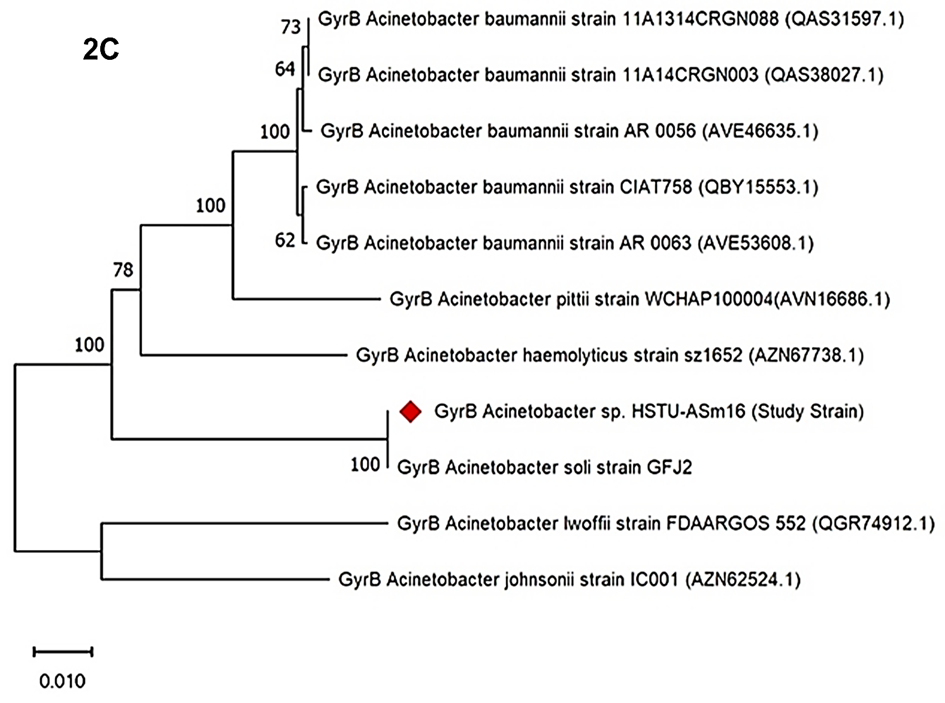

The phylogenetic tree based on gyrB gene sequences revealed the evolutionary relationships among Acinetobacter strains. The study strain, Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16, clustered closely with Acinetobacter soli strain GFJ2, supported by a bootstrap value of 100 (Figure 2C). Several Acinetobacter baumannii strains (11A1314CRGN088, 11A14CRGN003, AR 0056, CIAT758, AR 0063) formed a distinct cluster with bootstrap values ranging from 62 to 100. Acinetobacter pittii strain WCHAP100004 formed a separate lineage, while Acinetobacter haemolyticus strain sz1652 branched with a bootstrap value of 78. More distantly related species, including Acinetobacter lwoffii strain FDAARGOS 552 and Acinetobacter johnsonii strain IC001, were positioned at the base of the tree, indicating early divergence within the genus. Bootstrap values across the tree ranged from 62 to 100, reflecting the statistical support for each clade.

Figure 2C. gyrB gene phylogenetic tree of the strain Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16.

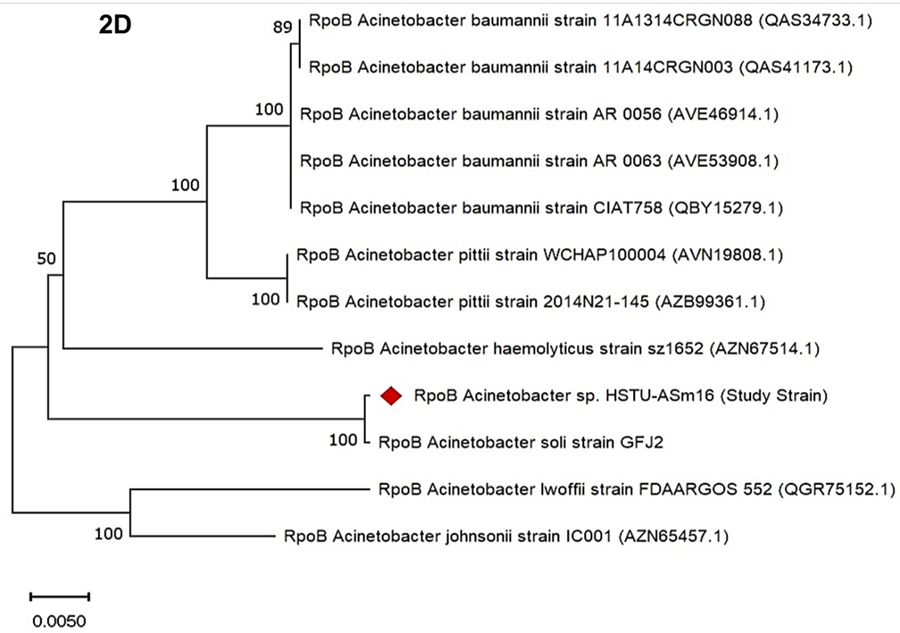

The phylogenetic tree based on rpoB gene sequences showed the evolutionary relationships among Acinetobacter strains. The study strain, Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16, clustered closely with Acinetobacter soli strain GFJ2, supported by a bootstrap value of 100 (Figure 2D). Several Acinetobacter baumannii strains (11A1314CRGN088, 11A14CRGN003, AR 0056, AR 0063, CIAT758) formed a distinct cluster with bootstrap values of 89 and 100. Acinetobacter pittii strains WCHAP100004 and 2014N21-145 formed a separate clade with a bootstrap value of 100, while Acinetobacter haemolyticus strain sz1652 branched off from the main clusters. More distantly related species, including Acinetobacter lwoffii strain FDAARGOS 552 and Acinetobacter johnsonii strain IC001, formed a basal clade with a bootstrap value of 100. Horizontal branch lengths indicate evolutionary distances, with the scale bar representing 0.0050. Bootstrap values across the tree ranged from 50 to 100, reflecting varying levels of support for the clades.

Figure 2D. rpoB gene phylogenetic tree of the strain Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16.

3.4. Analyses of the genomes

3.4.1. Average nucleotide identity (ANI) analysis of the strain

Average nucleotide identity (ANI) analysis was conducted using the JSpeciesWS platform to assess the genomic relatedness of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 with 14 phylogenetically related Acinetobacter reference genomes (Table 2). The highest ANI value (98.73%) for Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 was observed with Acinetobacter soli strain GFJ2 (CP016896.1). This value represents the only comparison exceeding 95% ANI, indicating the closest genomic relationship among the analyzed taxa. ANI values between HSTU-ASm16 and other Acinetobacter species, including A. baumannii, A. pittii, A. calcoaceticus, A. johnsonii, A. haemolyticus, A. lwoffii, and A. indicus, ranged from 83.72% to 84.66%, well below the commonly accepted species delineation threshold. In contrast, intra-species ANI values among reference A. baumannii strains were consistently high, ranging from 97.88% to 99.99%, confirming the reliability of the ANI analysis and the resolution of the dataset. Similarly, high ANI values were observed among A. pittii strains (up to 99.15%), supporting established species boundaries within the genus. Overall, the ANI results demonstrate that Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 is most closely related to A. soli strain GFJ2, while remaining genomically distinct from other examined Acinetobacter species, including clinically relevant A. baumannii strains.

Table 2. Average Nucleotide identity (ANI) of the Acinetobacter sp HSTU-ASm16.

Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16

| CP016896.1 Acinetobacter soli strain GFJ2 | CP020000.1 Acinetobacter calcoaceticus strain CA16 | CP022298.1 Acinetobacter johnsonii strain IC001 | CP026707.1 Acinetobacter baumannii strain AR 0056 | CP026711.1 Acinetobacter baumannii strain AR 0063 | CP027250.2 Acinetobacter pittii strain WCHAP100004 | CP032135.1 Acinetobacter haemolyticus strain sz1652 | CP033540.1 Acinetobacter pittii strain 2014S06-099 | CP033568.1 Acinetobacter pittii strain 2014N21-145 | CP035183.1 Acinetobacter baumannii strain 11A14CRGN003 | CP035184.1 Acinetobacter baumannii strain 11A1314CRGN088 | CP038500.1 Acinetobacter baumannii strain CIAT758 | CP046296.1 Acinetobacter lwoffii strain FDAARGOS 552 | CP046392.1 Acinetobacter indicus strain WMB-7 | ||

| Acinetobacter sp HSTU-ASm16 | * | 98. 73 | 84. 46 | 83. 80 | 84.03 | 84.16 | 84. 14 | 84.66 | 84. 15 | 84. 07 | 84.11 | 84.11 | 84.11 | 83. 74 | 83. 78 | |

| CP016896.1 Acinetobacter soli strain GFJ2 | 98. 73 | * | 84. 32 | 84. 14 | 83.93 | 84.20 | 84. 85 | 84.70 | 84. 36 | 84. 19 | 84.14 | 84.14 | 84.13 | 84. 00 | 84. 00 | |

| CP020000.1 Acinetobacter calcoaceticus strain CA16 | 84. 46 | 84. 19 | * | 84. 30 | 87.71 | 87.66 | 90. 25 | 84.88 | 90. 18 | 90. 14 | 87.66 | 87.64 | 87.66 | 84. 33 | 83. 99 | |

| CP022298.1 Acinetobacter johnsonii strain IC001 | 83. 82 | 84. 12 | 84. 30 | * | 84.71 | 84.28 | 84. 74 | 84.94 | 84. 44 | 84. 74 | 84.26 | 84.27 | 85.33 | 85. 81 | 86. 23 | |

| CP026707.1 Acinetobacter baumannii strain AR 0056 | 84. 02 | 83. 99 | 87. 69 | 84. 69 | * | 98.15 | 89. 13 | 85.37 | 89. 10 | 88. 99 | 99.62 | 99.62 | 97.88 | 85. 54 | 85. 25 | |

| CP026711.1 Acinetobacter baumannii strain AR 0063 | 84. 17 | 84. 26 | 87. 66 | 84. 26 | 98.16 | * | 89. 09 | 85.03 | 89. 11 | 88. 88 | 98.21 | 98.21 | 97.92 | 84. 66 | 84. 86 | |

| CP027250.2 Acinetobacter pittii strain WCHAP100004 | 84. 13 | 84. 85 | 90. 26 | 84. 75 | 89.14 | 89.08 | * | 85.42 | 96. 52 | 99. 15 | 89.13 | 89.14 | 89.21 | 85. 34 | 84. 72 | |

| CP032135.1 Acinetobacter haemolyticus strain sz1652 | 84. 64 | 84. 68 | 84. 89 | 84. 88 | 85.33 | 85.00 | 85. 38 | * | 85. 14 | 85. 23 | 85.10 | 85.11 | 85.30 | 85. 50 | 85. 49 | |

| CP033540.1 Acinetobacter pittii strain 2014S06-099 | 84. 15 | 84. 36 | 90. 18 | 84. 54 | 89.10 | 89.11 | 96. 52 | 85.16 | * | 96. 34 | 89.11 | 89.11 | 89.13 | 84. 90 | 84. 87 | |

| CP033568.1 Acinetobacter pittii strain 2014N21-145 | 84. 06 | 84. 17 | 90. 16 | 84. 74 | 88.99 | 88.88 | 99. 15 | 85.27 | 96. 34 | * | 88.88 | 88.88 | 89.04 | 85. 63 | 85. 07 | |

| CP035183.1 Acinetobacter baumannii strain 11A14CRGN003 | 84. 12 | 84. 05 | 87. 66 | 84. 30 | 99.62 | 98.20 | 89. 14 | 85.11 | 89. 11 | 88. 88 | * | 99.99 | 97.90 | 85. 23 | 84. 97 | |

| CP035184.1 Acinetobacter baumannii strain 11A1314CRGN088 | 84. 12 | 84. 05 | 87. 65 | 84. 30 | 99.62 | 98.20 | 89. 13 | 85.12 | 89. 11 | 88. 88 | 99.99 | * | 97.91 | 85. 17 | 84. 97 | |

| CP038500.1 Acinetobacter baumannii strain CIAT758 | 84. 10 | 84. 03 | 87. 68 | 85. 31 | 97.88 | 97.93 | 89. 21 | 85.28 | 89. 13 | 89. 04 | 97.91 | 97.91 | * | 84. 90 | 85. 24 | |

| CP046296.1 Acinetobacter lwoffii strain FDAARGOS 552 | 83. 72 | 84. 01 | 84. 33 | 85. 81 | 85.54 | 84.59 | 85.20 | 85.58 | 84. 75 | 85. 51 | 85.16 | 85.17 | 84.90 | * | 85. 62 | |

| CP046392.1 Acinetobacter indicus strain WMB-7 | 83. 78 | 84. 10 | 83. 94 | 86.20 | 85.21 | 84.87 | 84.71 | 85.49 | 84. 86 | 85.09 | 84.93 | 84.94 | 85.23 | 85.63 | * | |

3.4.2. Digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) analysis of the strain

Digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) analysis was performed to further assess the genomic relatedness of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 with phylogenetically related Acinetobacter reference strains using three recommended formulae (Table 3). The highest dDDH values were obtained in comparison with Acinetobacter soli, with values of 82.2% (Formula 1), 88.6% (Formula 2), and 86.2% (Formula 3). These values exceed the commonly accepted 70% species delineation threshold, indicating a close genomic relationship between HSTU-Asm16 and A. soli. The corresponding G+C content difference (1.86%) was within the range typically observed for strains belonging to the same species. In contrast, dDDH values calculated between Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 and other reference species including A. calcoaceticus, A. johnsonii, A. baumannii, A. pittii, A. haemolyticus, A. lwoffii, and A. indicus were consistently low, ranging from 15.6% to 21.1% across all formulae. These values are well below the species-level threshold, indicating clear genomic separation from these taxa. Correspondingly, G+C content differences for these comparisons ranged from 0.51% to 6.24%, supporting genomic divergence from non-A. soli species. Overall, the dDDH results demonstrate that Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 exhibits species-level genomic relatedness to A. soli while remaining distinct from other examined Acinetobacter species (Table 3).

Table 3. dDDH of the Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16.

| Reference strains genome compared | Formula:1 (HSP length / total length) DDH | Formula:2 (identities / HSP length) DDH Recommended | Formula:3 (identities / total length DDH | Difference in % G+C: (interpretation: distinct species) |

| Acinetobacter soli | 82.2 | 88.6 | 86.2 | 1.86 |

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus strain CA16 | 17.1 | 20.2 | 16.9 | 6.24 |

| CP022298.1 Acinetobacter johnsonii strain IC001 | 15.9 | 20.3 | 15.9 | 3.48 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii strain AR0056 | 17.1 | 20.2 | 16.8 | 5.85 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 17.2 | 20.4 | 17 | 5.97 |

| Acinetobacter pittii strain WCHAP100004 | 17.2 | 20.1 | 17 | 6.18 |

| Acinetobacter haemolyticus | 15.8 | 21.1 | 15.8 | 5.25 |

| Acinetobacter pittii strain 2014S06-099 | 17 | 20 | 16.8 | 6.15 |

| Acinetobacter pittii strain 2014N21-145 | 17.1 | 20 | 16.9 | 6.05 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii strain 11A14CRGN003 | 17 | 20.3 | 16.8 | 5.92 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii strain 11A1314CRGN088 | 17 | 20.3 | 16.8 | 5.92 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii strain CIAT758 | 16.9 | 20.4 | 16.8 | 5.95 |

| Acinetobacter lwoffii strain FDAARGOS_552 | 15.6 | 20.6 | 15.6 | 1.65 |

| Acinetobacter indicus strain WMB-7 | 16.3 | 20.1 | 16.2 | 0.51 |

3.4.3. Pangenome analysis of the strain

The comparative genomic analysis of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 revealed a dynamic genome architecture characterized by both conserved and variable regions. Alignment with closely related Acinetobacter species indicated the presence of large syntenic blocks, suggesting evolutionary conservation of core genomic regions. However, several regions displayed structural variations, including insertions, deletions, and potential inversions, reflecting genome plasticity and strain-specific adaptations. Notably, genomic islands unique to Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 were observed, which likely harbor genes associated with specialized metabolic functions, environmental adaptability, and potential plant-associated traits. These regions were absent in some related Acinetobacter strains, highlighting strain-specific genomic features. Additionally, evidence of horizontal gene transfer events was inferred from the presence of mobile genetic elements, including transposons and putative plasmid-borne sequences, indicating that HSTU-ASm16 may have acquired novel traits contributing to its ecological versatility. Overall, the genome of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 exhibits a combination of conserved syntenic regions and variable genomic segments, demonstrating both evolutionary conservation and adaptive potential. This genomic organization suggests that HSTU-ASm16 is equipped with genetic elements that may facilitate environmental survival, host interactions, and potentially beneficial plant-associated functions (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Pangenomic analyses of the strain Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16.

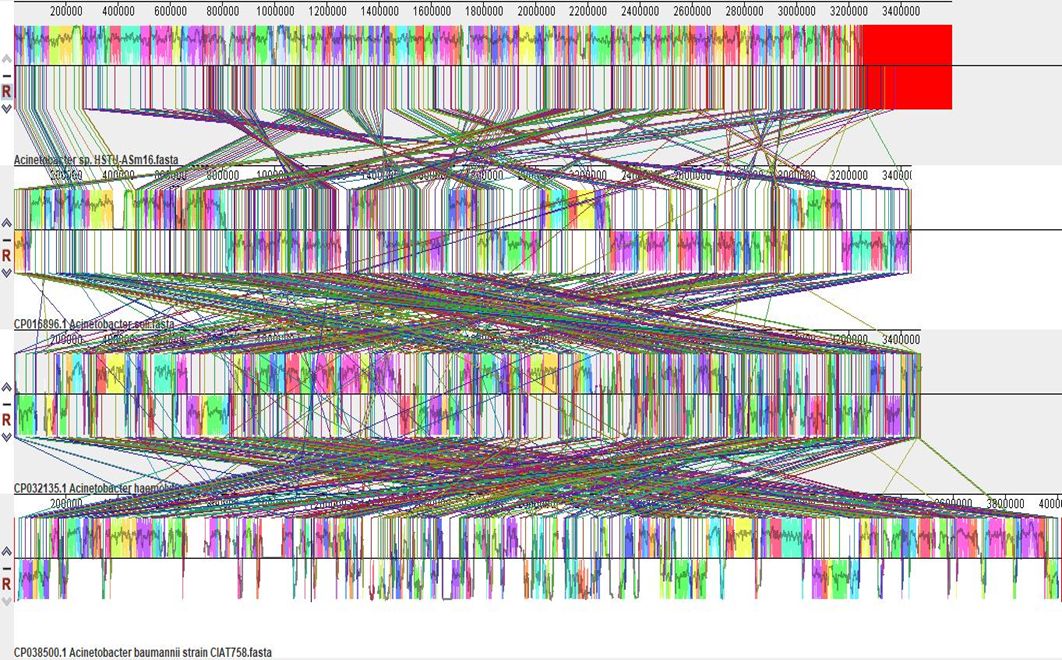

3.4.4. Progressive mauve analysis

Chromosome assemblies of the four samples were reordered according to M63 with Mauve and aligned by using progressive Mauve. The locally collinear blocks (LCB) of the genomes of three nearest strains namely Acinetobacter baumannii strain. Acinetobacter soli strain TO-A JPC and Acinetobacter bohemicus sp. with Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 strain was inspected using Progressive Mauve (Figure 4). The block outlines of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 genome encompassed a sort of sequence that is homologous to part of other genomes compared. It is assumed that the homologous LCBs are internally free from genomic rearrangement of genomes compared. In fact, the LCB in the genome of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-A Sm16 is connected by lines to similarly colored LCBs in the genomes of, Acinetobacter baumannii, Acinetobacter soli, Acinetobacter bohemicus, respectively. The boundaries of LCBs of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 and other strains taken comparison are generally considered as breakpoints of genome rearrangements. As seen in Figure 4, the LCBs of the Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 genome are near exactly matched with the LCBs of genomes taken for comparison. In addition, the reshuffling or rearrangements of sort of sequences are found in various LCBs compared to the LCBs of other nearest strains genomes. These results suggested that the Genome of the Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 strain is quite varied from its nearest strains, which indicates its evolutionary properties.

Figure 4. Progressive MAUVE of the strain Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16.

3.5. Plant growth-promoting (PGP) gene repertoire of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16

Genome analysis of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 revealed a diverse set of genes associated with plant growth–promoting (PGP) functions, spanning nitrogen metabolism, nutrient acquisition, phytohormone biosynthesis, stress tolerance, biofilm formation, and root colonization (Table 4). Genes involved in nitrogen-related processes were identified, including nifS (cysteine desulfurase) and nifU, together with Fe–S cluster assembly proteins (iscU and iscA). While these genes are not sufficient for complete nitrogen fixation, they are known to support nitrogen metabolism and redox enzyme maturation. Regulatory components linked to nitrogen sensing and assimilation were also present, such as glnK (P-II family nitrogen regulator), glnD (uridylyltransferase), gltB (glutamate synthase large subunit), and gltS (sodium/glutamate symporter), indicating capacity for ammonia assimilation and nitrogen homeostasis.

Table 4. Plant growth promoting associated genes in Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16.

| PGP activities description | Gene Name | Gene annotation | Chromosome location (HSTU-ASm16) | Locus Tag (HSTU-ASm16) | E.C. number |

| Nitrogen fixation | nifS | cysteine desulfurase | 130466..131683 | GN151_07910 | 2.8.1.7 |

| nifU | Fe-S cluster assembly protein | <1..>360 | GN151_15975 | - | |

| iscU | Fe-S cluster assembly scaffold | 130009..130395 | GN151_07905 | - | |

| iscA | Fe-S cluster assembly protein | 129666..129986 | GN151_07900 | - | |

| Nitrosative stress | glnK | P-II family nitrogen regulator | 27720..28058 | GN151_10595 | - |

| Nitrogen metabolism regulatory protein | glnD | Bifunctional uridylyl removing protein | 32454..35120 | GN151_11030 | 2.7.7.59 |

| Ammonia assimilation | gltB | glutamate synthase large subunit | 55704..60185 | GN151_04120 | 1.4.1.13 |

| gltS | sodium/glutamate symporter | 66337..67572 | GN151_00335 | ||

| ACC deaminase | dcyD | D-cysteine desulfhydrase | 4.4.1.15 | ||

| rimM | ribosome maturation factor RimM | 87556..88104 | GN151_04250 | - | |

| Siderophore | |||||

| Siderophore enterobactin | entC | isochorismate synthase EntC | 82047..83219 | GN151_06145 | 5.4.4.2 |

| rpoA | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit alpha | 184631..185638

| GN151_04780 | 2.7.7.6 | |

| rpoB | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta | 4013..8101 | GN151_14960 | 2.7.7.6 | |

| Plant hormones | |||||

| IAA production | trpS | tryptophan--tRNA ligase | 70493..71506 | GN151_11565 | 6.1.1.2 |

| trpB | tryptophan synthase subunit beta | 20270..21499 | GN151_02840 | 4.2.1.20 | |

| trpD | bifunctional anthranilate synthase glutamate amido transferase component | 36878..37927 | GN151_06640 | 2.4.2.18/4.1.3.27 | |

| Phosphate metabolism | phoU | phosphate signaling complex protein PhoU | 62637..63359 | GN151_10755 | 3.5.2.6 |

| phoB | phosphate response regulator transcription factor PhoB | 23655..24365 | GN151_08150 | - | |

| phoR | phosphate regulon sensor histidine kinase PhoR | 16563..17936 | GN151_12355 | 2.7.13.3 | |

| ppx | Exopolyphosphatase | 246977..248497 | GN151_01165 | 3.6.1.11 | |

| pntA | Re/Si-specific NAD(P)(+) transhydrogenase subunit alpha | 287779..288906 | GN151_01370 | 1.6.1.2 | |

| phoQ | two-component system sensor histidine kinase PhoQ | 16563..17936

| GN151_12355 | 2.7.13.3 | |

Biofilm formation | efp | elongation factor P | 39388..39957 | GN151_13300 | - |

| hfq | RNA chaperone Hfq | 129836..130240 | GN151_07050 | - | |

Sulfur assimilation and metabolism | cysK | cysteine synthase A | 41792..42790 | GN151_14005 | 2.5.1.47 |

| cysM | cysteine synthase CysM | 278546..279478 | GN151_01325 | 2.5.1.47 | |

| cysA | sulfate/thiosulfate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein CysA | 182909..183970 | GN151_02350 | - | |

| cysW | sulfate/thiosulfate ABC transporter permease CysW" | 183981..184871 | GN151_02355 | - | |

| cysN | sulfate adenylyl transferase subunit CysN | 57116..58729 | GN151_09470 | 2.7.7.4 | |

| cysD | sulfate adenylyl transferase subunit CysD | 58774..59682 | 58774..59682 | 2.7.7.4 | |

| cysH | Phosphor adenosine phosphosulfate reductase | 43413..44147 | GN151_00220 | 1.8.4.8 | |

| cysE | serine O-acetyltransferase | 48809..49618 | GN151_11085 | 2.3.1.30 | |

| cysK | cysteine synthase A | 278546..279478 | GN151_01325 | 2.5.1.47 | |

| cysS | cysteine--tRNA ligase | 82305..83726 | GN151_10470 | 6.1.1.16 | |

| Synthesis of resistance inducers | |||||

| Methanethiol | metH | methionine synthase | 85678..89364 | GN151_09585 | 2.1.1.13 |

| 2,3-butanediol | ilvB | acetolactate synthase large subunit | - | ||

| ilvN | acetolactate synthase small subunit | 305246..305737 | GN151_01435 | 2.2.1.6 | |

| ilvA | Serine, threonine dehydratase | 87259..88797 | GN151_07690 | 4.3.1.19 | |

| ilvC | ketol-acid reductoisomerase | 304197..305213 | GN151_01430 | 1.1.1.86 | |

| ilvY | HTH-type transcriptional activator IlvY | - | |||

| ilvD | Dihydroxy-acid dehydratase | 9229..10914 | GN151_12605 | 4.2.1.9 | |

| ilvM | acetolactate synthase 2 small subunits | 305246..305737 | GN151_01435 | 2.2.1.6 | |

| Isoprene | ispE | 4-(cytidine5'-diphospho)-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase | 38731..39552 | GN151_11420 | 2.7.1.148 |

gcpE/ ispG | flavodoxin-dependent (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl-diphosphate synthase | 95683..96798 | GN151_03190 | 1.17.7.1 | |

| Symbiosis-related | pyrC | Dihydroorotase | 742..1776 | GN151_08675 | 3.5.2.3 |

| tatA | Sec-independent protein translocase subunit TatA | 137790..138011 | GN151_03360 | - | |

| bacA | undecaprenyl-diphosphate phosphatase | 20717..21517 | GN151_10175 | 3.6.1.27 | |

| Oxidoreductase | osmC | peroxiredoxin OsmC | 12737..13300 | GN151_14510 | 1.11.1.15 |

| gpx | glutathione peroxidase | 1.11.1.9 | |||

| Hydrolase | ribA | GTP cyclohydrolase II | 61944..62546 | GN151_08340 | 3.5.4.25 |

| folE | GTP cyclohydrolase I FolE | 29508..30101 | GN151_06610 | 3.5.4.16 | |

| bglX | beta-glucosidase BglX | 3.2.1.21 | |||

| Root colonization | |||||

| Chemotaxis | cheB | chemotaxis-specificprotein-glutamate methyltransferase CheB | 3.1.1.61 | ||

| Adhesin production | pgaB | poly-beta-1,6-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine N-deacetylase PgaB | 101099..103174 | GN151_09650 | 3.5.1.- |

| pgaD | poly-beta-1,6-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine biosynthesis protein | 99382..99795 | GN151_09640 | - |

Multiple genes associated with phosphate metabolism and regulation were detected, including the phosphate signaling and uptake regulators phoU, phoB, phoR, and phoQ, along with ppx encoding exopolyphosphatase. The presence of pntA, encoding NAD(P)+ transhydrogenase, further suggests a role in maintaining redox balance during nutrient-limited conditions. The genome also encoded components related to iron acquisition, including the enterobactin biosynthesis gene entC, supporting potential siderophore-mediated iron scavenging. Genes involved in plant hormone–related pathways, particularly indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) precursor metabolism, were identified through the presence of tryptophan biosynthesis and utilization genes (trpS, trpB, and trpD), which are commonly associated with bacterial IAA production routes.

Genes implicated in ACC deaminase activity and stress modulation, such as dcyD (D-cysteine desulfhydrase), were present, potentially contributing to ethylene regulation under plant stress conditions. Additionally, oxidative and nitrosative stress response genes, including osmC (peroxiredoxin) and gpx (glutathione peroxidase), suggest an enhanced capacity to tolerate reactive oxygen species within the plant environment. A comprehensive set of genes involved in sulfur assimilation and metabolism was identified, including cysA, cysW, cysN, cysD, cysH, cysE, cysK, cysM, and cysS, supporting cysteine and methionine biosynthesis and sulfur uptake. Genes associated with the synthesis of volatile and resistance-inducing compounds, such as metH (methionine synthase) and enzymes of the 2,3-butanediol biosynthetic pathway (ilvB, ilvN, ilvA, ilvC, ilvD, and ilvM), were also detected. Pathways linked to isoprene biosynthesis were represented by ispE and ispG (gcpE), while genes associated with symbiosis and host interaction, including pyrC, tatA, and bacA, were present. The strain also encoded several hydrolases and oxidoreductases, such as ribA, folE, and bglX, which may contribute to metabolic versatility in the rhizosphere. Finally, genes involved in biofilm formation and root colonization were identified, including efp and hfq, as well as chemotaxis (cheB) and adhesion-related genes (pgaB and pgaD), supporting the potential for effective root surface attachment and endophytic colonization.

3.6. Abiotic Stress–Related Genes Identified in the Genome of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16

Genome annotation of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 identified multiple genes associated with responses to abiotic stresses (Table 5). Genes encoding heat shock and protein quality control systems were detected, including groL (chaperonin GroEL), dnaK and dnaJ (molecular chaperones), grpE (nucleotide exchange factor), and the heat shock sigma factor rpoH. Additional stress-associated genes included smpB, encoding the SsrA-binding protein, and lepA, encoding elongation factor 4. Genes associated with heavy metal resistance were present. The arsenic resistance–related genes arsB (arsenical efflux pump) and arsH (arsenical resistance protein) were identified, along with chrA, encoding a chromate efflux transporter. Genes involved in metal ion homeostasis included htpX, encoding a membrane-associated protease, and cobA, encoding uroporphyrinogen-III C-methyltransferase. Multiple genes related to osmotic and drought stress were identified. These included proA (glutamate-5-semialdehyde dehydrogenase), proB (glutamate 5-kinase), proP (glycine betaine/L-proline transporter), and proS (proline–tRNA ligase). Genes involved in compatible solute biosynthesis were also present, including betA (choline dehydrogenase) and betB (betaine-aldehyde dehydrogenase). In addition, the two-component system sensor histidine kinase kdbD was detected.

Table 5. Genes involved in different abiotic stresses available in Acinetobacter sp. HSTU- ASm16 genome.

| Activity description | Gene Name | Gene annotation | Chromosome location (HSTU-ASm16) | Locus Tag (HSTU-ASm16) | E.C. number |

| Heat Shock protein | smpB | SsrA-binding protein SmpB | 48842..49318 | GN151_11465 | - |

| groL | chaperonin GroEL | 24592..26226 | GN151_01625 | - | |

| dnaJ | molecular chaperone DnaJ | 25746..26864 | GN151_12660 | - | |

| dnaK | molecular chaperone DnaK | 5934..7880 | GN151_13390 | - | |

| rpoH | RNA polymerase sigma factor RpoH | 46074..46943 | GN151_07455 | - | |

| lepA | elongation factor 4 | 195684..197501 | GN151_02410 | 3.6.5.n1 | |

| grpE | nucleotide exchange factor GrpE | 5260..5814 | GN151_13385 | - | |

| Heavy metal resistance | |||||

| Arsenic tolerance | arsB | arsenical efflux pump membrane protein ArsB | 5908..6951 | GN151_14260 | - |

| arsB | arsenical efflux pump membrane protein ArsB | 5908..6951 | GN151_14260 | - | |

| arsH | Arsenical reseistance protein arsH | 6957..7661

| GN151_14265 | - | |

| Chromium resistance | chrA | Chromate efflux transporter | 3826..5013 | GN151_10895 | - |

| Magnesium transport | cobA | uroporphyrinogen-III C-methyltransferase | 20406..21800 | 20406..21800 | - |

| Zinc homeostasis | htpX | protease HtpX | 32333..33238 | GN151_01650 | 3.4.24.- |

| Drought resistance | proA | glutamate-5-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | 108655..109920 | GN151_03250 | 1.2.1.41 |

| proB | glutamate 5-kinase | 217255..218388 | GN151_02525 | 2.7.2.11 | |

| proP | glycine betaine/L-proline transporter ProP | 43930..45411 | GN151_11830 | - | |

| proS | proline--tRNA ligase | 94025..95737

| GN151_00475 | 6.1.1.15 | |

| betA | choline dehydrogenase | 157679..159337 | GN151_06435 | 1.1.99.1 | |

| betB | betaine-aldehyde dehydrogenase | 159427..160899 | GN151_06440 | 1.2.1.8 | |

| kdbD | two-component system sensor histidine kinase KdbD | 16563..17936 | GN151_12355 | 2.7.13.3 |

3.7. Genes associated with pesticide degradation

Genome annotation of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 revealed multiple genes encoding enzymes putatively involved in pesticide degradation and xenobiotic metabolism (Table 6). These genes were distributed throughout the chromosome, indicating that the pesticide-degrading potential is genomically integrated rather than confined to a specific operon or genomic island. The genome harbored the ampD gene encoding 1,6-anhydro-N-acetylmuramyl-L-alanine amidase (EC 3.5.1.28), a member of the amidohydrolase superfamily known for catalyzing amide bond cleavage in diverse xenobiotic compounds. In addition, several amidohydrolase family proteins (GN151_06015, GN151_07410, and GN151_11120) were identified, suggesting a broad enzymatic capacity for hydrolyzing organophosphate- and carbamate-like pesticides. Genes involved in aromatic compound metabolism were also detected, including paaC, encoding phenylacetate-CoA oxygenase subunit PaaC, which may facilitate the transformation of aromatic intermediates generated during pesticide degradation. The presence of pepA (leucyl aminopeptidase; EC 3.4.11.1) further suggests a role in downstream processing of degradation products.

Table 6. Genes associated with pesticide degradation available in Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 genome.

| Activity description | Gene Name | Gene annotation | Chromosome location (HSTU-ASm16) | Locus Tag (HSTU-ASm16) | E.C. number |

| Pesticide degrading | ampD | 1,6-anhydro-N-acetylmuramyl-L-alanineamidase | 11648..12238 | GN151_14070 | 3.5.1.28 |

| - | glpB | glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase subunit | 18507..20024 | GN151_01600 | 1.1.5.3 |

| pepA | leucyl aminopeptidase | 34288..35736 | GN151_10635 | 3.4.11.1 | |

| paaC | phenylacetate-CoA oxygenase subunit PaaC | 92071..92826 | GN151_09055 | ||

| - | Amidohydrolase | 47408..48562 | GN151_06015 | ||

| - | amidohydrolase family protein | 38596..39831

| GN151_07410 | ||

| - | amidohydrolase family protein | 57071..58504 | GN151_11120 | ||

| - | Glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase | 254..1393 | GN151_10480 | ||

| - | glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase | 25094..25810 | GN151_02860 | ||

| - | 3',5'-cyclic-nucleotide phosphodiesterase | 23281..24072 | GN151_01615 |

Moreover, the genome encoded glpB (glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase subunit; EC 1.1.5.3), along with multiple glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterases and a 3′,5′-cyclic-nucleotide phosphodiesterase. These enzymes are associated with phosphoester bond cleavage and are particularly relevant to the biodegradation of organophosphate pesticides. Given that diazinon contains phosphoester linkages, these phosphodiesterase-like enzymes may contribute to its initial hydrolytic transformation, either directly or through functional promiscuity reported for related hydrolases. Thus, the presence of diverse hydrolases, oxygenases, and phosphodiesterases highlights the strong genetic potential of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-ASm16 to participate in multi-step biodegradation pathways of structurally diverse pesticides.

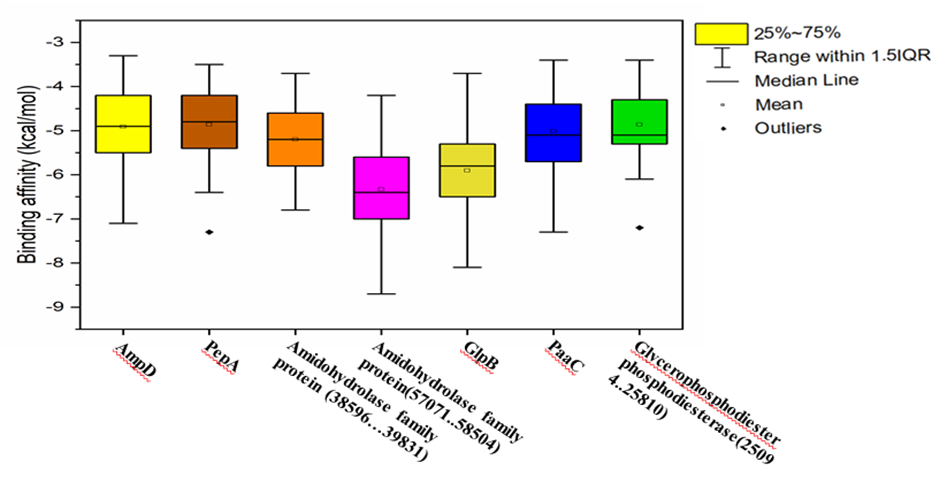

3.8. Virtual screening (docking) analysis of the model proteins with pesticides

Figure 5 illustrates the virtual screening of pesticide-degrading model proteins from Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16, based on their predicted binding affinities (kcal/mol). Virtual screening, employing molecular docking simulations, estimates the interaction strength between ligands and target proteins, with more negative binding affinity values indicating stronger interactions. Seven model proteins were analyzed: AmpD, PepA, two Amidohydrolase family proteins (38596–39831 and 57071–58504), GlpB, PaaC, and Glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase (25094–25810). Among these, the Amidohydrolase family protein (57071–58504) exhibited the strongest median binding affinity (-6.4 kcal/mol), suggesting the formation of the most stable protein–pesticide complexes. The other Amidohydrolase protein (38596–39831) had a median binding affinity of -5.2 kcal/mol. GlpB and PaaC demonstrated moderate binding affinities of -6.0 kcal/mol and -5.6 kcal/mol, respectively, consistent with their known roles in aromatic compound and glycerophosphodiester degradation. AmpD and PepA displayed median affinities of -5.0 kcal/mol and -4.8 kcal/mol, respectively, with PepA showing a notable outlier at -7.4 kcal/mol, indicating potential strong interactions with specific pesticides. Similarly, Glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase exhibited an outlier at -7.2 kcal/mol. Overall, these results identify the Amidohydrolase family protein (57071–58504) as the most promising candidate for pesticide degradation in Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16. The observed strong outliers for PepA and Glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase highlight additional proteins that may contribute to efficient pesticide breakdown, warranting further experimental validation.

Figure 5. virtual screening of pesticides degrading model protein-pesticides complex of the strain Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16.

3.9. Molecular docking and visualization of the pesticides-model putative pesticides degrading proteins

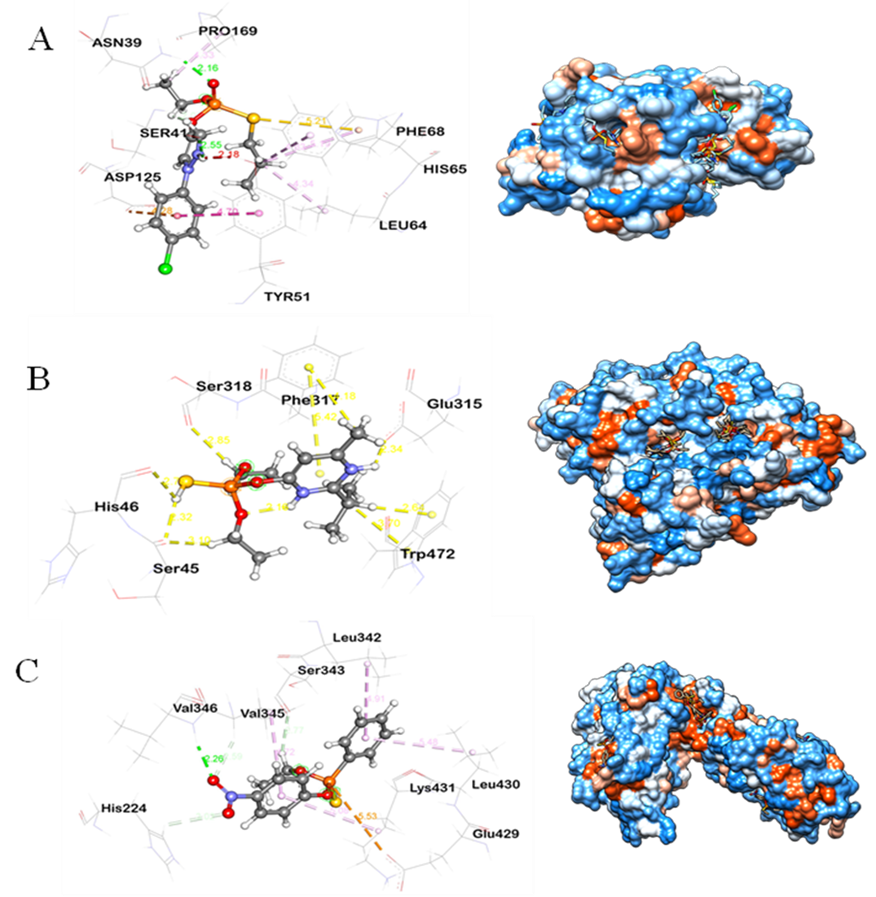

The conventional hydrogen bond interaction was observed for Ser41 and ASN39 with the side chain of the benzene ring attached, the O-atom, and the N-H atom of the phosphodiester of pyraclofos compound, while PRO169, PHE68, and LEU64 formed alkyl and π-alkyl bonds with the Cl-atom of pyraclofos, and Tyr51 formed. The AmpD protein and Phoxim insecticide docked complex ligand interactions were observed by the different residues (Figure 6A). In particular, Phe317 with Glu315 provided an attractive charge interaction with the phosphate atom. In addition, conventional hydrogen bond and pi sigma interactions were observed with the His45 and Ser46 residues. The interaction distances among the residues of the catalytic site were recorded within <3.9 Å. Another set of interactions is responsible for GlpB's high affinity for Diazinon (Figure 6B). Moreover, alpha/beta fold hydrolase (NR044454) protein-diazinon docked complex demonstrated the interaction with multiple residues (Figure 6C). In particular, conventional H-bond were made by His224, Ser231 to the O-atom of diazinon compound. Besides, Val346 with Lys431 also formed a conventional hydrogen bond. Multiple residues were interacted by alkyl, pi-alkyl, and carbon-hydrogen bonds namely, Met123, Leu208, Ile137, Phe133, His231 and Leu31 sequentially.

Figure 6. (A) Molecular docking visualization of the AmpD protein with Phoxim insecticide. (B) Molecular docking visualization of the GlpB with diazinon insecticide. (C) Molecular docking visualization of the PepA with EPN insecticide.

The integrated biochemical and genomic characterization of Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 highlights its potential as a multifunctional rice endophyte with both plant growth-promoting (PGP) traits and the genomic capacity to participate in organophosphate pesticide degradation. Biochemically, HSTU-Asm16 showed catalase and oxidase activity, citrate utilization, carbohydrate fermentation, and production of extracellular hydrolases (amylase, protease, xylanase), traits commonly associated with metabolically flexible endophytes that can access diverse carbon sources and modify plant cell wall components to facilitate colonization and nutrient exchange. The absence of detectable CMCase activity, while other hydrolases are retained, suggests a significant microbial specialization towards particular polysaccharide substrates rather than broad cellulolysis [41]. This targeted degradation indicates that the microbe has evolved to efficiently process specific complex carbohydrates, a trait observed in organisms thriving in competitive environments [42]. Such enzymatic specialization fosters commensal or mutualistic interactions with host plants by allowing the microbe to access nutrients without aggressive tissue maceration. This strategic metabolic approach benefits both the microbe and the plant by enabling nutrient acquisition or cell wall modification for colonization, promoting a balanced and symbiotic relationship [43].

Whole-genome phylogenetic reconstruction, leveraging both read-mapping and reference alignment approaches, robustly positioned HSTU-Asm16 in close evolutionary proximity to Acinetobacter soli strains. This phylogenetic placement was further corroborated by analyses of housekeeping gene trees [34]. To ascertain the genetic relatedness with greater resolution, the JSpeciesWS platform was employed to generate Average Nucleotide Identity and other pairwise genomic metrics. ANI, a robust method for bacterial species demarcation, typically shows ≥95% identity among strains of the same species [44, 45]. Concurrently, digital DNA-DNA hybridization (dDDH) values and their associated confidence intervals were obtained using the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator, a tool commonly used for prokaryotic species delineation [46]. Collectively, the results from these platforms affirmed HSTU-Asm16's strong affinity to A. soli, while also revealing significant strain-level differentiation across multiple comparisons. Further enhancing the phylogenetic resolution, REALPHY-derived whole-genome phylogenies, inferred from mapped reference alignments, provided intricate details of genome-scale evolutionary relationships, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of HSTU-Asm16's taxonomic position [47].

The extensive genome rearrangements, horizontal gene transfer, and the acquisition of mobile genetic elements observed in HSTU-Asm16 are hallmarks of adaptive strategies in environmental Acinetobacter species. This genomic plasticity enables bacteria to thrive in diverse and dynamic environments and to form host associations [48-49]. Comparative genomic studies on Acinetobacter baumannii have shown that pangenome analysis can reveal structural variations and constant genetic permutation among strains, indicating high genomic plasticity [50-51]. Similarly, research on Acinetobacter haemolyticus has identified chromosomes organized into syntenic blocks interspersed with hypervariable regions rich in unique gene families and signals of horizontal gene transfer [52]. These findings support the idea that pangenome and synteny analyses are crucial for understanding the evolutionary dynamics of bacterial genomes. Although the isolate does not represent a new species, its distinct genomic repertoire related to pesticide biodegradation highlights its strain-level novelty and functional relevance. Bacterial genome diversification and the development of niche-specific functions are often driven by continuous processes of niche exploration, diversification, and adaptation [53]. Comparative genomics helps reveal these adaptive mechanisms, particularly in host-niche specialization [54]. The ability of Acinetobacter species to adapt to a wide range of environmental conditions is linked to their genomic plasticity [55] with niche-specific adaptive mutations and genes mediating fitness in different habitats [48]. Bacterial genome rearrangements, including gene loss, duplication, and acquisition, are significantly influenced by horizontal gene transfer, frequently mediated by mobile genetic elements like plasmids and transposons [55]. The Acinetobacter genus, being ancient and diverse, undergoes outstanding diversification largely through horizontal transfer and allelic recombination at specific hotspots [56]. This process, including conjugation, is a major contributor to bacterial genome plasticity, evolution, and adaptation, particularly in the transfer of traits like multi-drug resistance [57]. Acinetobacter baumannii, for instance, is noted for its high genomic plasticity and its predisposition to exchange MGEs through HGT [58].

The results highlights that gene mining of HSTU-Asm16 revealed several key plant growth-promoting activities, including nitrogen fixation, siderophore biosynthesis for iron acquisition, indole-3-acetic acid synthesis, and ACC deaminase for hormone modulation, along with capabilities for phosphate solubilization and sulfur assimilation. These features, supported by genes for chemotaxis, adhesion, and biofilm formation, enable efficient root colonization and stable endophytism, consistent with findings on other endophytic bacteria [41,59 ,60]. Additionally, HSTU-Asm16 possesses a notable complement of organophosphate-degrading enzymes, such as carboxylesterases, amidohydrolases, phosphodiesterases, and organophosphorus hydrolase homologs, indicating its potential in bioremediation of organophosphate contaminants through enzymatic breakdown [61-63]. Functionally, gene mining revealed multiple loci associated with classical plant growth-promoting activities: (i) nitrogen-related genes (nif clusters and electron transport components for alternative nitrogenases), (ii) siderophore biosynthesis pathways such as enterobactin-type systems for iron acquisition, (iii) indole-3-acetic acid synthetic pathways and ACC deaminase for modulation of plant hormone signaling, and (iv) phosphate solubilization and sulfur assimilation genes that can improve nutrient availability. The presence of chemotaxis, adhesion, and biofilm formation genes supports efficient root colonization and stable endophytism. These features align with reports that endophytic bacteria often carry suites of genes enabling nutrient exchange, stress amelioration, and intimate host colonization [41, 64]. Of special interest is HSTU-Asm16’s complement of putative organophosphate-degrading enzymes. Genome mining detected genes encoding carboxylesterases, amidohydrolases, phosphodiesterases, and homologs of organophosphorus hydrolase. These microbial enzymes are recognized for their role in the bioremediation of organophosphate compounds, which are often environmental contaminants [61, 62]. Molecular docking provided mechanistic plausibility for predicted biodegradation. Docking of representative organophosphate ligands, such as paraoxon [65] and chlorpyrifosmethyl oxon [66] against candidate hydrolases yielded energetically favorable poses with canonical catalytic residues (Ser/His/Asp triads and metal-binding motifs) forming hydrogen bonds, electrostatic contacts, and hydrophobic stabilization within distances consistent with catalysis (<4 Å). These observed interactions mirror catalytic geometries described in biochemical studies of phosphotriesterases and related hydrolases [67]. While in-silico docking cannot replace biochemical assays, the concordance between genomic presence of candidate hydrolase genes and favorable docking interactions, as explored through computational enzymology [68], strengthens the inference that HSTU-Asm16 encodes functional degradative pathways. Docking scores were interpreted as relative indicators of binding propensity rather than absolute binding free energies. A cutoff value of ≤ –7.0 kcal/mol was applied to prioritize biologically relevant enzyme–ligand complexes, as this threshold is commonly used in virtual screening and approximately corresponds to micromolar-range binding affinity. This criterion is appropriate for environmental substrates such as pesticides, which are not optimized for high-affinity binding. All selected complexes were further evaluated based on binding pose stability and interactions with conserved catalytic residues. Although this study did not experimentally verify diazinon degradation by the investigated strain, several endophytic bacteria and phylogenetically related taxa have previously been reported to metabolize diazinon under minimal nutrient conditions. In this context, the present genome-centric and molecular docking analyses provide predictive and mechanistic insight into the potential of the strain to interact with diazinon at the enzyme level. The identification of conserved organophosphate-degrading enzyme families, coupled with favorable ligand–protein interactions observed in silico, suggests a genetically encoded capacity for diazinon transformation. Nevertheless,strain-specific biochemical validation using GC–MS/MS and metabolite profiling is required and will be addressed in future experimental investigations.

Taken together, HSTU-Asm16 represents a genomically equipped endophyte with a dual capacity. It carries genes for nutrient acquisition and stress resistance that likely support plant growth under diverse conditions, and it harbors enzyme candidates with plausible mechanisms for organophosphate turnover [69]. These dual capacities argue for its potential deployment as a bioinoculant that could both boost rice productivity and contribute to in-situ pesticide detoxification an attractive strategy in integrated pest and soil health management [70]. However, to translate genomic and in-silico predictions into application, targeted biochemical validation is required: heterologous expression and kinetic characterization of the candidate hydrolases, gene knockouts or transcriptomics under pesticide exposure, and greenhouse/field trials to measure colonization, plant responses, and pesticide dissipation kinetics [71].

Acinetobacter sp. HSTU-Asm16 is a metabolically versatile, genomically distinct endophytic strain from rice that combines plant growth-promoting features with a predicted enzymatic toolkit for organophosphate degradation. Comparative genomics (ANI/dDDH, pangenome and synteny analyses) places the strain within the A. soli-related clade but highlights accessory genomic regions and rearrangements indicative of strain-level novelty. Genome annotation uncovered genes linked to nutrient acquisition, stress tolerance, colonization and multiple classes of hydrolases implicated in OP pesticide degradation; molecular docking supports plausible active-site interactions with representative OP compounds. Future work should prioritize biochemical validation of the hydrolases, gene expression studies under pesticide challenge, and controlled plant assays to confirm PGP efficacy and bioremediation potential before field application. Altogether, HSTU-Asm16 is a promising candidate for integrated strategies aimed at improving rice health while mitigating chemical pesticide residues. We emphasize that docking results provide preliminary, comparative insights into enzyme–substrate compatibility and do not substitute for molecular dynamics simulations or experimental validation, which will be addressed in further studies for sustainable green agrosystem.

The authors gratefully acknowledge IRT of Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University (HSTU), for financial support. We also thank all contributors for their valuable roles in the preparation of this manuscript. In addition, this study addresses about 10% AI-assisted text for arranging and formatting the manuscript following the journal policy.

This research was supported by the grants from the Institute of Research and Training (IRT)-Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University (HSTU) in fiscal year 2021-2022 at Dinajpur, Bangladesh.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This study did not involve any experiments on human participants or animals; therefore, formal written informed consent was not required by the Institutional Review Board. All figures in this study were created; therefore, no permission for reuse is required for any figure presented herein.

The assembled and annotated genome sequence was deposited in the NCBI and provided accession number as Acinetobacter soli strain HSTU-ASm16 (Accession number: JARWII000000000, BioSample: SAMN34186007; BioProject: PRJNA955703).

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

.

You are free to share and adapt this material for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit.