J. Biosci. Public Health. 2026; 2(1)

Living facilities in slums face significant challenges with water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), contributing to high risk of some diseases among children and adolescents. This study assesses WASH practices, related communicable disease prevalence, treatment-seeking behaviors, and associated socio-demographic factors in this vulnerable population. A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 500 school-aged children and adolescents (5-17 years) in urban slums in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Data on socio-demographics, WASH-related communicable diseases (diarrhea, common flu, dengue, malaria, and chicken pox), and others were collected via structured questionnaires. Descriptive statistics were used; bivariate associations were explored. Among participants, 73.8% reported at least one WASH-related communicable disease in the last three months, with the common flu predominant. Hygiene practices were suboptimal; 51.0% used common taps (supply) water for drinking, 47.6% consumed unpurified water, and only 16.4% always washed hands with soap before eating. Treatment-seeking was delayed, with 49.0% waiting more than 7 days. The occurrence of communicable diseases was significantly higher among children from lower-income households, those with lower parental education, users of untreated water, shared sanitation facilities, and inconsistent handwashing practices (all p < 0.01). Interventions targeting hygiene education and infrastructure are urgently needed to reduce inequities and align with SDG 6.

Urban slums in an overpopulated country like Bangladesh are characterized by overcrowding, inadequate infrastructure, and limited access to basic services for living, which may contribute to the risk of communicable diseases among children and adolescents [1]. Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) practices are critical for preventing infections, as poor sanitation and hygiene facilitate pathogen transmission. Globally, inadequate WASH is estimated to cause 1.4 million preventable deaths annually, with diarrheal diseases and acute respiratory infections accounting for the majority, disproportionately affecting children in low- and middle-income countries [2]. More than 1,000 children under five die every day from WASH-related diseases, highlighting the urgent need for improved access [3].

In Bangladesh, rapid urbanization has resulted in approximately 50% of the urban population residing in slums, with Dhaka hosting millions in informal settlements characterized by high density and poor environmental conditions [4, 5]. These areas exhibit persistent WASH deficits, including widespread toilet sharing, reliance on public water sources, and limited handwashing facilities, driving elevated rates of communicable diseases such as diarrhea, respiratory infections, cholera, and typhoid [6, 7]. Recent prospective cohort studies in Dhaka's slums, such as Mirpur, have demonstrated strong associations between poor household WASH status and increased risks of severe cholera and typhoid fever, emphasizing the role of sanitation infrastructure in pathogen transmission [8, 9]. Unplanned urbanization further amplifies these risks through overcrowding and environmental degradation, rendering school-aged children and adolescents particularly vulnerable due to immature immune systems, increased play-based exposures, and school environments [10]. By focusing on children and adolescents, the research addresses a critical gap in WASH literature, which has traditionally prioritized children under five, despite persistent vulnerabilities in older age groups within urban slum settings [11]. Achieving equitable WASH access is essential for advancing Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 and reducing health inequities in rapidly urbanizing contexts like Bangladesh.

This study refers to WASH-related communicable diseases whose occurrence is influenced directly or indirectly by water, sanitation, hygiene, and environmental conditions prevalent in urban slum settings. While diarrhea is directly WASH-mediated, respiratory, vector-borne, and viral infections are indirectly associated with poor WASH conditions through overcrowding, environmental contamination, inadequate hygiene, and stagnant water. Therefore, in this study, diarrhea, the common flu, malaria, dengue, and chickenpox were collectively referred to as communicable diseases, encompassing waterborne, respiratory, vector-borne, and vaccine-preventable infections. Furthermore, describe WASH practices and communicable disease prevalence, examine treatment-seeking behaviors, and identify associations with socio-demographic factors. By focusing on this age group, the research addresses a gap in WASH literature, which often prioritizes under-5s.

2.1. Study population and sampling

This cross-sectional study was conducted in four randomly selected urban slums in Dhaka North and South City Corporations in Bangladesh from April to June 2024. Participants were school-aged children and adolescents (5-17 years) living in these slums. Convenience sampling yielded 500 complete responses from 530 participants (81% response rate). As an inclusion criterion, only those aged 5-17 years, slum residents, and willing to participate in this study were included. Children with ages outside the range and incomplete survey data were excluded. Responses from parents and guardians on behalf of some participants were considered to minimize data collection errors.

The sample size was calculated using the following equation:

Here,

n = number of samples

z = critical value of the normal distribution

p = expected prevalence estimate

q = (1-p) = expected non-prevalence

d = precision limit or proportion of sampling error

The critical value (z) included as 1.96 for a 95 % confidence level. We made the best assumption for calculating the sample size, the prevalence estimate would be 50%. The precision limit or proportion of sampling error (d) is usually considered to be 5% confidence limit.

Therefore,

A total of 500 children and adolescents are taken as a sample which represents the population.

2.2. Data collection

A well-structured questionnaire was used to collect socio-demographics (age, sex, income, family type, parental education/occupation), WASH-related communicable disease information (past 3 months: yes/no), treatment-seeking (patterns, timing, preferences), and hygiene (water source, purification, handwashing, toilet sharing) through physical interview. Participants were selected randomly without any bias.

2.3. Measures and data collection of WASH-related communicable disease prevalence

To measure the prevalence of communicable diseases among the school-age slum-living children in the last three months, the five most common infectious diseases, both water- and vector-borne, are taken into consideration (diarrhea, common flu, dengue, malaria, and chickenpox). In addition, common flu was defined as an acute respiratory illness with fever, cough, sore throat, and nasal congestion indirectly linked to WASH through poor hand hygiene, overcrowding, and shared sanitation. Before recording data, suffering from diseases was confirmed from the diagnosis report from their parents, with the exception of some flu or fever cases. Responses were taken as “yes/no” along with the frequency of getting sick in the last three (03) months with specific responses (no idea, never, once, 2-3 times, 4-5 times, and >6 times).

2.4. Collection of treatment-seeking behaviors data

To understand the treatment-seeking behavior of the study population, they were asked about their treatment-seeking patterns during the time of ailments with the following responses: no treatment, self-treatment, and visiting health professionals; how many days they take to visit any health professional (1-3 days, 4-6 days, >7 days); and what type of treatment they and their families usually prefer (regular scientific treatment, alternative medicines, or both simultaneously).

2.5. Collection of hygiene practice-related data

To measure the hygiene practices, the following questions were asked with the mentioned responses: source of drinking water (piped into dwelling, public tap/standpipe); water purification process (boiling or as is); wash hands with soap before eating (never, rarely, sometimes, always); wash hands with soap after using the toilet (never, rarely, sometimes, always); and sharing of toilet in their housing (yes and no).

2.6. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages) using SPSS v25 and Excel 2021. Bivariate analyses (chi-square) identified associations; multivariate regression is suggested for the future.

3.1. Socio-Demographic characteristics

Participants were predominantly early adolescents (10-14 years: 48.8%), male (51.4%), with low school attendance (48.6%). Monthly income was 10,000-20,000 BDT for 43.2%; fathers were primary earners (60.0%). Families were mostly nuclear (66.2%) with 4-7 members (69.6%). Parental education was low, with >50% of mothers were working (Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of socio-demographic characteristics (n=500).

| Variables | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Age group | 5-9 years 10-14 years 15-17years | 217 244 39 | 43.40 48.80 7.80 |

| Sex | Male Female | 257 243 | 51.40 48.60 |

| Attend school | Yes No | 243 257 | 48.60 51.40 |

| Involvement in employment | Yes No | 106 394 | 21.20 78.80 |

| Monthly family income | <10,000 10,000-20,000 >20,000 | 178 216 106 | 35.60 43.20 21.20 |

| Main wage earner | Father Mother Others | 298 128 74 | 59.60 25.60 14.80 |

| Family type | Nuclear Joint | 331 169 | 66.20 33.80 |

| Total family members | 1-3 members 4-7 members >7 members | 77 348 75 | 15.40 69.60 15.00 |

| Qualification of the mother | No formal education Primary incomplete Completed primary Secondary incomplete Completed secondary | 122 135 131 73 39 | 24.40 27.00 26.20 14.60 7.80 |

| Qualification of the father | No formal education Primary incomplete Completed primary Secondary incomplete Completed secondary | 76 102 180 111 131 | 15.20 20.40 16.00 22.20 26.20 |

| Mother’s occupation | Housewife Worker Not alive | 235 256 9 | 47.00 51.20 1.80 |

| Father’s occupation | Unemployed Worker Not alive | 152 327 21 | 30.40 65.40 4.20 |

3.2. Prevalence of WASH-related communicable diseases and treatment practice

To measure the prevalence of communicable diseases, this study measured the occurrence of five of the most common infectious diseases: diarrhea, the common flu, malaria, dengue, and chickenpox (Table 2). Among all the 500 participants, 73.80% (n=369) of people responded that they have suffered from any of the mentioned diseases, and 21.20% (n=106) responded that they have not suffered from any of the mentioned diseases. 73.8% (n=369) reported diseases in the past 3 months (common flu: ~57%), 21.2% none, and 5.0% unsure. Frequency: less (47.8%), moderate (39.8%), severe (12.4%). Sickness episodes: once (26.8%), 2-3 times (31.0%).

Table 2. Prevalence of WASH-related communicable diseases among school-aged children in the last three months.

*Diseases | Yes | No | ||

Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

| Diarrhea | 182 | 64.40 | 318 | 63.60 |

| Common flu | 310 | 62.00 | 190 | 38.00 |

| Malaria | 59 | 11.8 | 441 | 88.20 |

| Dengue | 75 | 15.00 | 425 | 85.00 |

| Chicken pox | 150 | 30.00 | 350 | 70.00 |

*Prevenance of these diseases may vary in different seasons in a year.

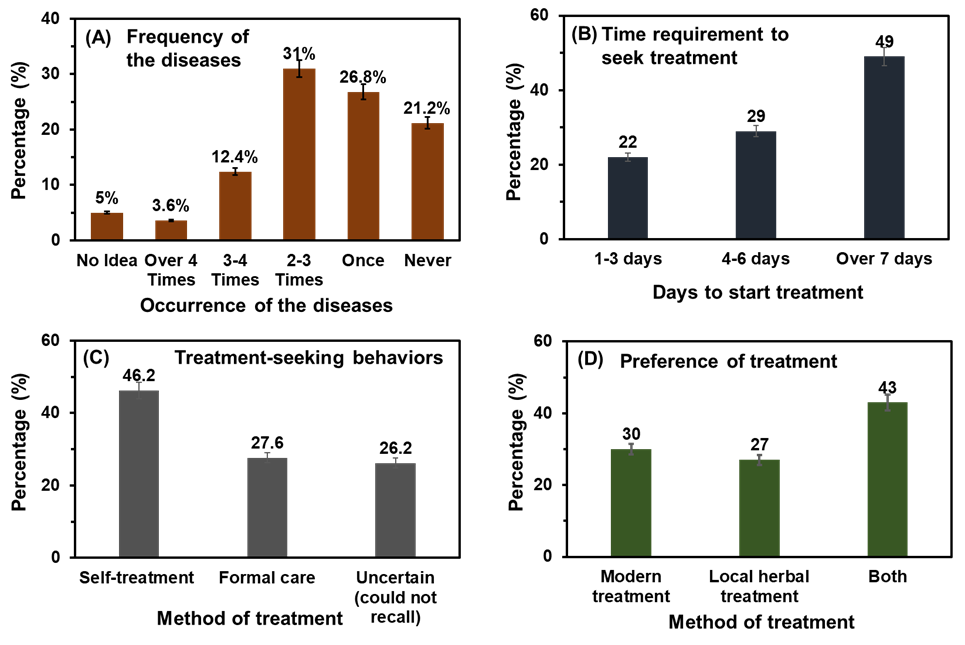

The occurrence of the diseases is illustrated in Figure 1A. According to the responses from the participants about how many times they were sick, 5.00% (n=25) of people had no idea about the occurrence of the disease, 21.20% (n=106) responded that they were never sick, 26.80% (n=134) said they were sick only once, 31.00% (n=155) said they were sick between two and three times, 12.40% (n=62) responded for four to five times, and 3.60% (n=18) mentioned that they were sick more than six times. Figure 1B shows the time requirement to seek treatment by the participants. Among all the participants, 22.00% (n=110) said they seek immediate treatment (within 1-3 days) during any sickness in general, 29.00% (n=145) seek treatment after 4-6 days of sickness, and the rest, 49.00% (n=245), start treatment after 7 days (one week) of sickness depending on the symptoms and severity. Moreover, financial ability sometimes delays or influences the start of treatment and the way of treatment as well. Treatment-seeking behaviors are stated in Figure 1C; during sickness, 46.2% start self-treatment, 27.6% visit professionals’ healthcare givers, and 26.2% are unsure and could not recall the treatment method in the last sickness. Preference of treatment is another important parameter for slump people. Among the sample populations, 30.40% (n=152) of respondents usually prefer modern scientific treatment, while 27.00% (n=135) said they prefer alternative medicines, for example, herbal treatments, and the remaining 42.60% (n=213) follow both alternative and scientific treatment methods (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. (A) Comparative percentages of occurrences of diseases mentioned in Table 2 among the study population in Table 2 in the last three months, (B) time requirement to seek treatment, (C) treatment-seeking pattern of participants, and (D) preference of treatment by the participants.

3.3. WASH related hygiene practices by the participants

Table 3 summarizes the WASH practices of the respondents. Nearly half of the households relied on common tap (supply) water (49%), while the remaining 51% used piped water into dwellings, including tubewells and other sources. 52% of respondents reported boiling water before drinking, whereas 48% consumed water without any treatment. Hand hygiene practices before eating were suboptimal, with only 16.4% reporting always washing hands with soap; the majority practiced handwashing inconsistently (sometimes: 42.8%; rarely: 34.6%), and 6.2% never washed hands with soap before meals. The majority of the study population, 86.82%, uses shared toilets, and the remaining 13.18% have toilets that are not shared with the other slum dwellers. Moreover, 6.20% (n=31) of the study participants never wash their hands with soap before eating, 34.60% (n=173) of the study participants rarely wash their hands, 42.80% (n=214) use soap sometimes, and 16.40% (n=82) always use soap to wash their hands before eating. Handwashing with soap after toilet use was more common than before eating. Among all the participants, 19.80% (n=99) rarely use soap, 44.60% (n=223) sometimes use soap, and 35.60% (n=178) always use soap to wash hands after using the toilet. Overall, the findings indicate substantial gaps in optimal WASH practices among the study population.

Table 3. WASH- related practices of respondents (n=500).

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Source of drinking water | Common tab water source (supply water) | 245 | 49 |

Piped into dwelling (tubewell and others). | 255 | 51 | |

| Water purification process | Boiling | 260 | 52 |

Without treatment (as it is) | 240 | 48 | |

| Handwashing with soap before eating | Always | 82 | 16.40 |

| Sometimes | 214 | 42.80 | |

| Rarely | 173 | 34.6 | |

| Never | 31 | 6.20 | |

| Sharing of toilet facilities | Shared | 435 | 87 |

| Not Shared | 65 | 13 | |

| Handwashing with soap after using the toilet | Always | 178 | 35.60 |

| Sometimes | 223 | 44.60 | |

| Rarely | 99 | 19.80 |

3.4. Correlations of Socio-Demographic variables with WASH, communicable diseases and hygiene.

Table 4 presents the associations between sociodemographic characteristics, WASH-related factors, and the occurrence of at least one communicable disease among school-aged children and adolescents in urban slums. Disease prevalence showed an increasing trend with age, from 69.8% among children aged 5-9 years to 78.1% among those aged 15-17 years; however, this association was not statistically significant (p = 0.181). No significant difference was observed by sex (p = 0.764).

Strong socioeconomic gradients were evident. Children whose fathers were day laborers had a significantly higher prevalence of communicable diseases at 80.2% compared with those whose fathers were engaged in small business or service occupations at 64.6% (p = 0.005). Lower parental education was consistently associated with higher disease occurrence. Prevalence was highest among children whose fathers (82.8%) and mothers (84.0%) had no formal education and decreased progressively with higher educational attainment (both p < 0.001).

Table 4. Association of sociodemographic characteristics with occurrence of at least one communicable disease among school-aged children and adolescents in the last three months living in urban slums of Bangladesh (n = 500).

| Characteristics | Category | Disease present n (%) | Disease absent n (%) | χ² | p-value |

| Age group (years) | |||||

| 5–9 | 118 (69.8) | 51 (30.2) | 3.42 | 0.181 | |

| 10–14 | 176 (74.9) | 59 (25.1) | |||

| 15–17 | 75 (78.1) | 21 (21.9) | |||

| Sex | Male | 194 (74.6) | 66 (25.4) | 0.09 | 0.764 |

| Female | 175 (72.9) | 65 (27.1) | |||

| Father’s occupation | Day laborer | 162 (80.2) | 40 (19.8) | 12.67 | 0.005 |

| Rickshaw puller | 94 (76.4) | 29 (23.6) | |||

| Small business/service | 113 (64.6) | 62 (35.4) | |||

| Mother’s occupation | Homemaker | 241 (75.3) | 79 (24.7) | 4.91 | 0.086 |

| Income-generating work | 128 (70.3) | 54 (29.7) | |||

| Father’s education | No formal education | 173 (82.8) | 36 (17.2) | 21.45 | <0.001 |

| Primary | 119 (71.7) | 47 (28.3) | |||

| Secondary or above | 77 (61.6) | 48 (38.4) | |||

| Mother’s education | No formal education | 189 (84.0) | 36 (16.0) | 24.98 | <0.001 |

| Primary | 117 (70.5) | 49 (29.5) | |||

| Secondary or above | 63 (60.0) | 42 (40.0) | |||

| Monthly household income (BDT) | <10,000 | 158 (83.6) | 31 (16.4) | 26.31 | <0.001 |

| 10,000–20,000 | 147 (72.4) | 56 (27.6) | |||

| >20,000 | 64 (57.7) | 47 (42.3) |

Household income demonstrated a clear inverse relationship with disease occurrence. Children from the family with earnings of less than 10,000 BDT per month had the highest prevalence (83.6%), compared with 57.7% among those from households earning more than 20,000 BDT (p < 0.001). Overall, findings in Table 4 highlight that lower socioeconomic status, limited parental education, inadequate water access, and shared sanitation facilities are significantly associated with increased occurrence of communicable diseases among school-aged children and adolescents living in urban slums.

Table 5. Association between WASH practices and occurrence of at least one communicable disease among school-aged children and adolescents living in urban slums of Bangladesh (n = 500).

| Variable | Category | Disease present n (%) | Disease absent n (%) | χ² | p-value |

| Source of drinking water | Piped into dwelling | 151 (61.6) | 94 (38.4) | 12.48 | <0.001 |

| Public tap / standpipe | 218 (84.3) | 41 (15.7) | |||

| Water treatment practice | Boiling | 163 (62.2) | 99 (37.8) | 18.91 | <0.001 |

| No treatment | 206 (86.1) | 32 (13.9) | |||

| Sanitation facility | Non-shared toilet | 36 (52.5) | 33 (47.5) | 21.34 | <0.001 |

| Shared toilet | 333 (77.8) | 95 (22.2) | |||

Handwashing with soap before meals | Always | 45 (55.3) | 37 (44.7) | 14.02 | 0.003 |

| Sometimes / Rarely / Never | 324 (78.6) | 88 (21.4) | |||

Handwashing with soap after toilet use | Always | 104 (58.4) | 74 (41.6) | 16.87 | <0.001 |

| Sometimes / Rarely | 265 (81.2) | 61 (18.8) |

Table 5 shows the associations between WASH practices and the occurrence of at least one communicable disease among school-aged children and adolescents living in urban slums. Noticeable differences in disease occurrence were observed across all WASH indicators. Children from households relying on public tap or standpipe supply water had a substantially higher prevalence of communicable diseases (84.3%) compared with those using piped water into the dwelling (61.6%) (p < 0.001). Similarly, consumption of untreated drinking water was associated with a markedly higher disease prevalence 86.1% than drinking boiled water of 62.2% (p < 0.001). Sanitation-related factors showed strong associations with disease occurrence. Children using shared toilet facilities experienced a significantly higher prevalence of communicable diseases (77.8%) compared with those with access to non-shared toilets (52.5%) (p < 0.001). Hygiene behaviors were also strongly associated with disease burden. Participants who did not consistently wash hands with soap before meals (sometimes/rarely/never) had a higher prevalence of disease (78.6%) than those who always practiced handwashing before eating (55.3%) (p = 0.003). Likewise, inconsistent handwashing with soap after toilet use was associated with a higher prevalence of communicable diseases (81.2%) compared with consistent handwashing (58.4%) (p < 0.001). Overall, Table 5 demonstrates that unsafe water sources, lack of water treatment, shared sanitation facilities, and poor hygiene practices are significantly associated with the occurrence of WASH-related communicable diseases among school-aged children and adolescents in urban slum areas.

This study demonstrates a high burden of WASH-related communicable diseases among school-aged children and adolescents living in urban slums of Dhaka, with nearly three-quarters of participants reporting at least one illness in the preceding three months. Diarrheal disease directly linked to unsafe water and poor sanitation—remains a major contributor, while respiratory infections, vector-borne diseases (malaria and dengue), and viral infections (chicken pox) reflect the indirect effects of inadequate WASH conditions, including overcrowding, environmental contamination, and limited hygiene practices. Results reveal suboptimal WASH practices and a high prevalence of communicable diseases (73.8%) among school-aged children and adolescents in Dhaka's urban slums, consistent with prior research linking inadequate sanitation, unpurified water, and shared facilities to elevated risks of diarrheal and respiratory infections [6, 12]. The predominance of common flu and widespread toilet sharing (86.8%) underscore infrastructure deficits that facilitate pathogen transmission, aligning with cohort findings from Mirpur slums showing associations between poor WASH and severe cholera or typhoid [8, 9].

Socio-demographic factors, particularly higher family income and parental education, emerged as protective against poor WASH practices and disease prevalence, supporting evidence that socioeconomic gradients drive disparities in resource access and hygiene behaviors [13]. For instance, the inferred strong associations (e.g., p < 0.001 for water purification in higher-income groups) highlight economic barriers limiting preventive measures in low-income households [14]. Younger children displayed higher disease rates and inconsistent hygiene, likely reflecting developmental needs for supervision and greater susceptibility, warranting age-targeted interventions like school-based education [15, 16].

Toilet sharing and larger family sizes were linked to poorer hygiene and increased disease risk, tied to overcrowding and resource dilution findings echoed in studies showing shared sanitation as a reservoir for pathogens and elevated diarrheal risks [17,18]. Delayed treatment-seeking (49% >7 days) and preferences for alternative medicines may exacerbate outcomes, often rooted in economic and cultural factors [19].

Overall, the findings highlight that WASH-related diseases among school-aged children in the 5-17 age group in urban slums are not solely a consequence of water quality but rather the result of a complex interaction between sanitation, hygiene behaviors, environmental conditions, and socioeconomic vulnerability [20]. Integrated interventions focusing on improved sanitation infrastructure, hygiene promotion, vector control, seasonal flu control, and school-based health education are essential to reducing disease burden and advancing progress toward Sustainable Development Goal-6 in urban slum settings [16, 21, 22]. Comparative research in similar low- and middle-income contexts could further validate these patterns.

This study demonstrates a high prevalence of communicable diseases (73.8%) among school-aged children and adolescents in urban slums of Dhaka, closely linked to suboptimal WASH practices, including widespread consumption of unpurified water, infrequent handwashing with soap, and extensive toilet sharing. Socioeconomic factors particularly low household income and parental education-were strongly associated with poorer hygiene behaviors and increased disease risk. These findings highlight the persistent WASH-related health inequities in urban slum settings and underscore the need for integrated interventions, including improved sanitation infrastructure, targeted hygiene promotion, and socioeconomic support. Prioritizing WASH access for this age group is critical to reducing communicable disease burden and achieving Sustainable Development Goal 6 in rapidly urbanizing low-resource contexts. Future longitudinal and interventional studies are recommended to evaluate causal pathways and the impact of scaled WASH programs.

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to everyone who contributed to the successful completion of this research project. We are especially thankful to the residents of the slums in Dhaka city for their valuable time and willingness to participate in our interviews, making data collection possible. Our sincere thanks also go to our project supervisor and faculty member of the Department, whose guidance and support were instrumental in carrying out this study.

There is no funding source to carry out this study.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This study did not involve any experiments on human participants or animals; therefore, formal written informed consent was not required. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. Participation was entirely voluntary, and respondents were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their information throughout the study. Authors are solely responsible for any kind of misinformation.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

.

You are free to share and adapt this material for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit.