J. Biosci. Public Health. 2026; 2(1)

Endophytic bacteria represent a promising biological solution for sustainable agriculture and pesticide bioremediation. This study reports the isolation and comprehensive characterization of the novel endophytic bacterial strain Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 from Oryza sativa L. tissues exposed to pesticide stress. Integrated biochemical, genomic, and in silico analyses revealed their dual functionality in chlorpyrifos degradation and plant growth promotion. The genome sequence analysis (ANI, dDDH, pangenomics, Progressive Mauve, and phylogenetic analysis) confirmed the strains belong to the Citrobacter species. The isolates exhibited phosphate solubilization, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production, and 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase-producing genes in their annotated genome. Genome annotation identified organophosphate-degrading genes (opd, phn, ampD, pepD), suggesting potential for pesticide degradation. In silico docking analyses validated strong interactions (–6.5 to –8.0 kcal·mol⁻¹) between key enzymes (AmpD, PepE, GlpQ, carboxylesterase, amidohydrolase, and phosphonatase) and cypermethrin, diazinon, and crotoxiphos. Phylogenomic analyses (ANI and dDDH) confirmed their distinct taxonomic positions, indicating functionally distinct endophytic strains. Citrobacter sp. strain HSTU-ABk15 as a genetically robust, multifunctional endophyte with significant potential for eco-friendly pesticide remediation and sustainable rice cultivation.

Feeding a global population that is expected to reach 10 billion by 2050 challenges modern agriculture. Meeting this demand requires adopting sustainable farming practices to ensure food security, conserve resources, and reduce environmental harm [1, 2]. Developing and using innovative, environmentally responsible alternatives to chemical pesticides, such as new antimicrobial bioactive compounds, is essential. Overusing chemical pesticides causes new pest outbreaks, harms non-target species, and leaves persistent residues in soil and water [3]. The demand for better antimicrobial agents underscores the importance of such alternatives. These challenges make agricultural innovation focused on sustainability and environmental responsibility urgent. Beneficial microorganisms, particularly bacterial endophytes, are essential for sustainable crop production. These bacteria inhabit plant tissues without causing harm and form symbiotic relationships that enhance plant growth and stress tolerance [4]. They promote growth by fixing nitrogen, increasing phosphate availability, and producing plant hormones such as auxins, gibberellins, and cytokinins [4]. Nitrogen-fixing endophytes, including Novosphingobium sediminicola, Ochrobactrum intermedium, Bradyrhizobium, Kosakonia, and Paraburkholderia, contribute to nutrient cycling and improve soil fertility [4]. Endophytes also help plants resist stress by producing lytic enzymes, siderophores, and antioxidants, or by activating plant defenses against disease [5]. Additionally, endophytic bacteria support environmental remediation by degrading organic pollutants, including pesticides, dyes, and other xenobiotics. They achieve this by adsorbing pollutants, internalizing them, and using enzymes to convert them into less harmful substances [6]. Bacteria from genera such as Bacillus, Acinetobacter, Enterobacter, Serratia, Pseudomonas, Flavobacterium, and Sphingomonas can degrade the pesticide chlorpyrifos [7, 8].

Endophytic bacteria are an important source of bioactive secondary metabolites, such as alkaloids, phenols, flavonoids, peptides, steroids, and terpenoids. Many of these compounds have antimicrobial, antifungal, antitumor, and anticancer effects [4,9]. Recent advances in genome mining and bioinformatics tools, such as antiSMASH, have enabled the identification of a wide range of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) associated with these metabolites [10]. These genomic studies also help find genes that support plant growth, nutrient uptake, and stress tolerance [4]. Although endophytes are known for their many functions, there remains a significant research gap in fully characterizing new strains of important crops such as rice (Oryza sativa L.). Most research has focused on single aspects, such as plant growth promotion, pollutant breakdown, or secondary metabolite production.

However, only a few studies have used a genome-based approach to explore the combined abilities of new endophytes. The present study addresses this gap by isolating and characterizing a novel bacterial endophyte, Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15, from rice tissues. The study aimed to (i) identify and classify the isolates through metabolic profiling and whole-genome sequencing; (ii) evaluate their plant growth-promoting traits, including nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, and phytohormone-producing genes; (iii) assess their chlorpyrifos degradation potential using in silico protein modelling and molecular docking. These findings provide new insights into the multifunctional potential of rice-associated endophytic bacteria and highlight their applications in sustainable agriculture, bioremediation, and the discovery of novel bioactive compounds.

2.1. Isolation and biochemical characterization

Endophytic bacteria, Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15, was isolated from surface-sterilized roots of healthy rice (Oryza sativa L.) following established protocols [11, 12]. Specifically, isolation was performed on chlorpyrifos-enriched minimal salt agar containing 0.2% chlorpyrifos to select for pesticide-tolerant endophytes. Subsequently, purified colonies were characterized biochemically according to Bergey’s Manual (1996) using catalase, oxidase, citrate utilization, urease, and triple sugar iron tests [13]. Finally, hydrolytic enzyme activities (cellulase, xylanase, pectinase) were assessed by clear-zone formation on specific agar plates [14].

2.2. Genomic analysis of Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15: DNA extraction, whole genome sequencing, assembly, and annotation

Genomic DNA of the strain was isolated using the Promega (USA) Genomic DNA Extraction Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA purity and concentration were assessed with a Promega DNA spectrophotometer. Whole-genome shotgun sequencing of the Citrobacter sp. isolate was carried out on the Illumina MiniSeq platform (Illumina, USA) using paired-end sequencing chemistry. Genomic libraries were prepared from purified DNA using the Nextera XT Library Preparation Kit according to standard procedures.

Raw reads were quality-checked with FASTQC v1.0.0, and adapter removal, quality trimming, and length filtering were performed using the FASTQ Toolkit. After filtering, approximately 248.95 Mbp of high-quality data were assembled de novo using SPAdes v3.9.0 to generate contigs, which were subsequently arranged into scaffolds. The assembled sequences were further refined and aligned using Progressive Mauve v2.4.0. Genome annotation was performed using both the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP v4.5) and Prokka. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST and pMLST) was conducted through the Illumina Bacterial Analysis Pipeline v1.0.4. Functional categorization of predicted protein-coding genes was performed using the COG database via the RAST annotation server. Functional insights were derived from PGAP annotations [14, 15]. Phylogenetic relationships based on housekeeping genes (recA, gyrB, and rpoB) were inferred using MEGA XI with 1,000 bootstrap replications. Genes involved in nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, phytohormone biosynthesis, biofilm formation, and abiotic stress tolerance were identified by the following approaches [15].

2.2. Virtual screening and catalytic triad visualization

We retrieved the three-dimensional structures of the organophosphate insecticides used in this study from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and compiled them before virtual screening. We optimized the ligand structures and minimized their energy using the MMFF94 force field with the steepest-descent algorithm. Virtual screening was performed in PyRx, in which each ligand was docked to the selected protein targets. For each enzyme, we ran multiple docking simulations to find possible active-site interactions and confirm binding patterns. We exported the binding affinities (kcal/mol) and visualized them in R. Enzymes with docking scores above 7 kcal/mol were studied further, and we created close-up images of the catalytic centers, such as Ser-His-Asp and Ser-His-His triads, to explore possible mechanisms of insecticide degradation.

2.3. Protein modeling and docking

Candidate pesticide-degrading enzymes were, identified and three-dimensional structures were, predicted using the SWISS-MODEL and I-TASSER platforms [16]. The quality and structural reliability of the modeled proteins were evaluated through multiple validation tools, including ERRAT, VERIFY-3D, and Ramachandran plot analysis. Molecular docking analyses were performed using PyRx and Discovery Studio to investigate enzyme–ligand interactions. The docking results demonstrated strong binding affinities, with calculated binding energies ranging from −6.5 to −8.0 kcal·mol⁻¹, and identified key catalytic residues potentially involved in chlorpyrifos degradation [17, 18].

2.4. Comparative genomic analyses: Phylogenetic analyses and average nucleotide identity (ANI)

Housekeeping genes (16S rRNA, rpoB, recA, and gyrB, which are essential for basic cellular function) were extracted from the draft genome, aligned individually, and concatenated for phylogenetic reconstruction. Neighbor-joining trees (phylogenetic trees built using a distance-based method) for both the 16S rRNA gene and the concatenated markers were generated in MEGA X (a molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software). Whole-genome phylogeny (evolutionary relationship analysis using the entire genome) was constructed using REALPHY 1.12 (http://www.realphy.unibas.ch/realphy/), incorporating the genome of the strain and those of its nearest relatives. ANI values (Average Nucleotide Identity, a measure of genomic similarity; specifically, ANIb refers to BLAST-based ANI) between Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 and closely related taxa were calculated using the JSpeciesWS platform (http://jspecies.ribhost.com/jspeciesws).

2.5. Digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH)

Genome similarity was further assessed by digital DNA–DNA hybridization using the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC 3.0; https://ggdc.dsmz.de/), comparing the target strain with 14 phylogenetically related Citrobacter genomes [14, 15].

2.6. Genome alignment (MAUVE)

Whole-genome alignment across Citrobacter genomes was executed using the MAUVE algorithm to visualize syntenic regions and structural variations. Colored synteny blocks facilitated comparison of genome architecture. Pangenome analysis was additionally performed using publicly available servers as described by [12] to evaluate gene distribution patterns across species [14, 15].

2.7. Genome-level comparison

To explore genomic features, the draft genome of Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 was compared to closely related, recently reported Citrobacter genomes. Circular and linear genome visualizations were generated using CGView (http://www.cgview) and BRIG v0.95, respectively. BLAST+ analyses (70–90% identity threshold; E-value 10) were run to map sequence similarity. Genome collinearity and synteny were assessed using Progressive Mauve (http://darlinglab.org/mauve/mauve.html). In silico DNA–DNA hybridization with the 15 closest genomes was performed using the GGDC server [14, 15].

2.8. Functional Genes: Plant growth promotion, stress tolerance, and insecticide degradation

Plant growth-promoting traits encoded in Citrobacter genomes were mined from PGAP-annotated files and compared with those of reference endophytic strains. Genes associated with nitrogen fixation (e.g., nifA–nifZ, iscAUR), nitrosative stress tolerance (norRV, ntrB, glnK, nsrR), ammonia assimilation, ACC deaminase production, siderophore biosynthesis (enterobactin), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) synthesis, phosphate metabolism, sulfur assimilation, biofilm formation, chemotaxis, root colonization, trehalose metabolism, antioxidant defense (e.g., superoxide dismutase), hydrolase activity, adhesin formation, symbiosis-related pathways, and antimicrobial peptide synthesis were identified. Genes linked to abiotic stress tolerance such as cold-shock, heat-shock, drought-stress, and heavy-metal resistance determinants were also catalogued. Furthermore, organophosphate-degrading genes, including carboxylesterase, organophosphorus hydrolase (opd), amidase, phosphonatase, phosphotriesterase, and phosphodiesterase, were identified from the literature and curated accordingly [19, 20].

3.1. Biochemical characterization of the newly isolated endophytic bacteria

Three bacterial strains; Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15, isolated from rice plants were biochemically characterized (Table 1). All strains were positive for oxidase, citrate utilization, catalase, urease, TSI, and carbohydrate (lactose, sucrose, dextrose) utilization, but negative for indole. Motility and indole/urease test results varied among strains. In the Methyl red test, HSTU-ABk15 was negative, while the opposite pattern was observed in the Voges-Proskauer test. The strain displayed xylanase, amylase, CMCase and protease activity.

Table 1. Biochemical test of Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15.

| Oxidase | Citrate | Catalase | MIU | Mortality | Urease | VP | MR | TSI | Lactose | Sucrose | Dextrose | Maltose | CMCase | Xylanase | Amylase | Protease | |

| Citrobacter sp. HSTU- ABk15 | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

3.2. Genome sequencing of the strain

Fast QC quality assessment of the paired-end raw reads (R1 and R2) generated from Illumina sequencing showed a GC content of 53.4%, which falls within the acceptable range (40–70%) for high-quality bacterial genomes (Table 2). The filtered reads were assembled de novo using SPAdes v3.9.0, producing 573 contigs with a total genome size of approximately 4.75 Mb.

Table 2. Genomic feature of the strain Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15.

| Features | Annotation statistics |

| Genome | Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 |

| Domain | Bacteria |

| Taxonomy | Bacteria; Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 |

| Size | 4,754,666 |

| GC content | 53.4 |

| N50 | 198784 |

| L50 | 8 |

| Number of contigs (with PEGs) | 131 |

| Number of subsystems | 573 |

| Number of coding’s sequences | 4375 |

| Number of RNAs | 100 |

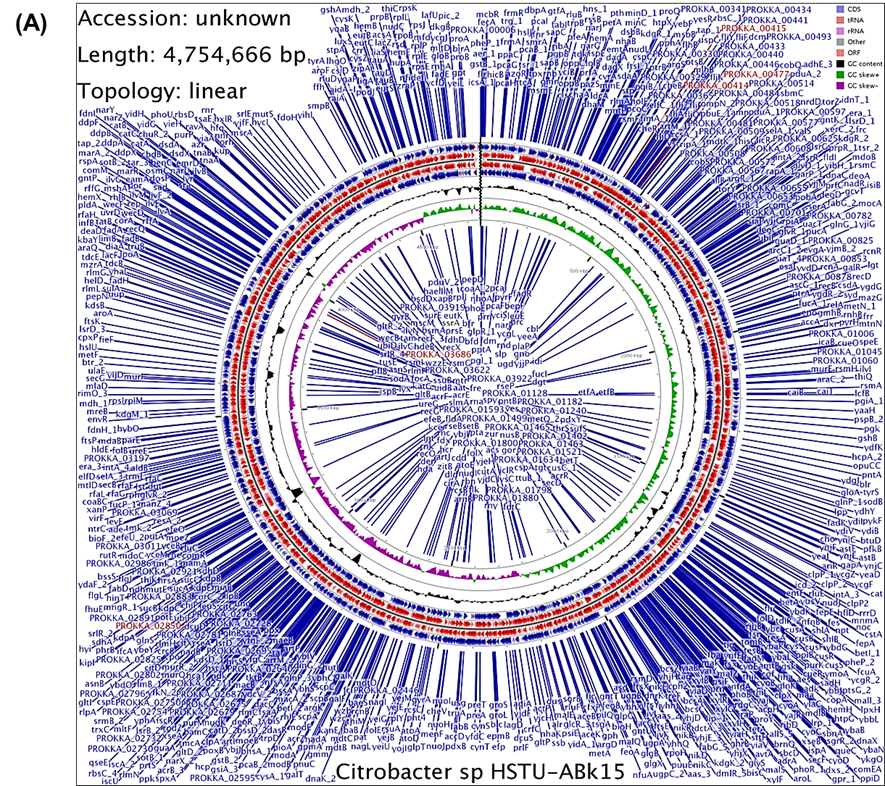

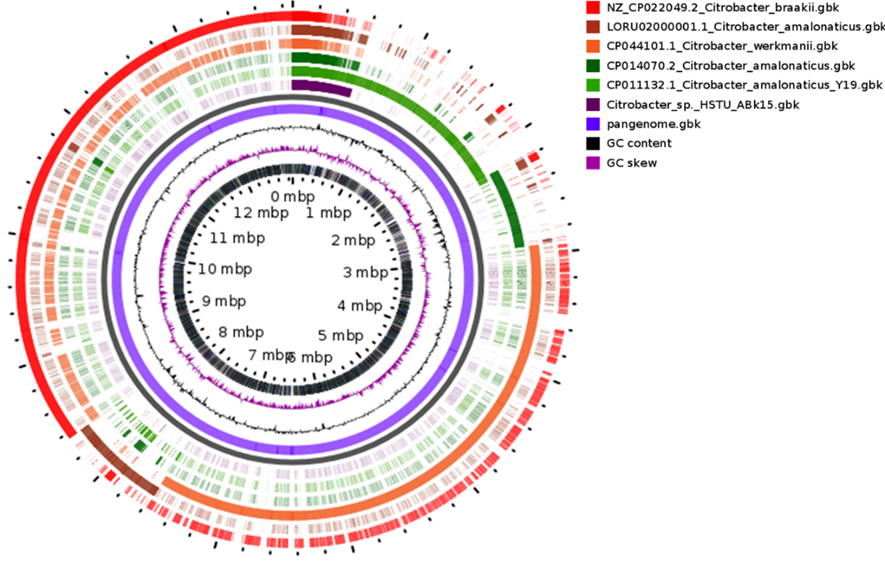

The draft genome of Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 comprised a single circular chromosome without plasmids (Figure 1A). Annotation through PGAP identified 4,375 protein-coding genes and 100 RNA genes. RAST analysis further revealed key assembly statistics, including an N50 of 198,784 bp and an L50 of 8. Subsystem distribution indicated that approximately 63% of the genome was assigned to functional categories, while the remaining 37% consisted of genes outside defined subsystems (Figure 1B). Major functional groups included genes involved in amino acid metabolism (451), carbohydrate metabolism (725), and protein metabolism (302), highlighting the metabolic versatility of the strain.

Figure 1. Genome annotation map of Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15. A) Circular genome map of Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABK15 showing gene distribution on forward and reverse strands, RNA features, GC content, and GC skew for the 4.75 Mb linear chromosome constructed using Linux programming. B) Subsystem coverage and functional category distribution of the genome annotated using the RAST (SEED) server.

3.3. Average nucleotide identity (ANI) of the strain

Average nucleotide identity (ANI) is study to the most relevant comparative parameter used for bacterial species determination. Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 genome was compared with 14 different closely related bacterial species where maximum result shown up 98% nucleotide sequence identity with CP 014070.2, CP057150.1, CP057632.1, CP064180.1, LORU02000001.1, CP04136 where the reference vaules are gradualy 99.4,99.13,99.80,99.85,99.24,98.53. Considering that highest ANI cut off value of Citrobacter species HSTU-ABK 15 with Citrobacter amalonaticus strain CA71 as indicating 99.85%. Also, all the values are showing high similarity with others reference genome as all showed 81% or above ANI value. Here the lowest value was 81.75 with refer to CP024677.1 Citrobacter freundii strain UMH. Table 3a showed all results of ANI.

Table 3a. Average nucleotide identity (ANIb) of Citrobacter sp. strain HSTU-ABk15.

| Citrobacter_sp._HSTU-ABk15 | CP011132.1_Citrobacter_amalonaticus_ Y19 | CP014015.2_Citrobacter_amalonaticus_ strain_FDAARGOS_122 | CP014070.2_Citrobacter_amalonaticus_ strain_FDAARGOS_165 | CP022273.1_Citrobacter_freundii_strain_ 18-1 | CP024677.1_Citrobacter_freundii_strain_ UMH16 | CP044098.1_Citrobacter_portucalensis_ strain_FDAARGOS_617 | CP044101.1_Citrobacter_werkmanii_strain_FDAARGOS_616 | CP057150.1_Citrobacter_sp._RHB35-C17 | CP057632.1_Citrobacter_sp._RHB20-C15 | CP064180.1_Citrobacter_amalonaticus_ strain_CA71 | LORU02000001.1_Citrobacter_amalonaticus_strain_FDAARGOS_166 | NZ_CP022049.2_Citrobacter_braakii_strain_FDAARGOS_290 | NZ_CP039327.1_Citrobacter_portucalensis_strain_Effluent_1 | CP041362.1_Citrobacter_amalonaticus_ strain_133355. | |

| Citrobacter_sp._HSTU-ABk15 | * | 91.52 | 95.07 | 99.13 | 81.78 | 81.73 | 81.93 | 81.84 | 99.09 | 99.87 | 99.85 | 98.74 | 81.82 | 81. 89 | 99.19 |

| CP011132.1_Citrobacter_amalonaticus_Y19 | 91. 26 | * | 91.95 | 91.27 | 81.83 | 81.29 | 81.63 | 81.41 | 91.30 | 91.26 | 91.24 | 91.47 | 81.76 | 81. 47 | 91.27 |

| CP014015.2_Citrobacter_amalonaticus_strain_FDAARGOS_122 | 94. 99 | 92.21 | * | 94.88 | 81.93 | 81.96 | 81.99 | 82.02 | 95.00 | 94.96 | 94.93 | 95.05 | 82.16 | 82. 02 | 95.02 |

| CP014070.2_Citrobacter_amalonaticus_strain_FDAARGOS_165 | 99. 04 | 91.52 | 94.87 | * | 81.85 | 81.59 | 81.87 | 81.82 | 98.95 | 98.89 | 98.87 | 98.70 | 82.03 | 81. 79 | 99.09 |

| CP022273.1_Citrobacter_freundii_strain_18-1 | 81. 81 | 81.86 | 81.94 | 81.97 | * | 98.23 | 93.97 | 90.27 | 81.84 | 81.84 | 81.77 | 82.23 | 92.10 | 94. 16 | 81.83 |

| CP024677.1_Citrobacter_freundii_strain_UMH16 | 81. 75 | 81.73 | 81.98 | 81.69 | 98.31 | * | 93.96 | 90.31 | 81.82 | 81.85 | 81.83 | 81.97 | 92.04 | 93. 84 | 81.86 |

| CP044098.1_Citrobacter_portucalensis_strain_FDAARGOS_617 | 81. 92 | 81.83 | 81.99 | 81.80 | 93.78 | 94.01 | * | 90.23 | 81.86 | 81.79 | 81.68 | 81.86 | 92.29 | 97. 85 | 81.83 |

| CP044101.1_Citrobacter_werkmanii_strain_FDAARGOS_616 | 81. 88 | 81.66 | 81.98 | 81.87 | 90.27 | 90.33 | 90.24 | * | 81.86 | 81.88 | 81.93 | 81.91 | 90.41 | 90. 55 | 81.87 |

| CP057150.1_Citrobacter_sp._RHB35-C17 | 99. 13 | 91.66 | 95.10 | 99.11 | 81.84 | 81.78 | 81.82 | 81.81 | * | 99.03 | 99.02 | 98.79 | 81.91 | 81. 86 | 99.11 |

| CP057632.1_Citrobacter_sp._RHB20-C15 | 99. 80 | 91.47 | 95.04 | 98.94 | 81.85 | 81.88 | 81.83 | 81.94 | 98.96 | * | 99.66 | 98.62 | 81.95 | 82. 03 | 99.20 |

| CP064180.1_Citrobacter_amalonaticus_strain_CA71 | 99. 85 | 91.59 | 95.03 | 9.00 | 81.81 | 81.72 | 81.76 | 81.84 | 98.93 | 99.66 | * | 98.70 | 81.86 | 81. 94 | 99.19 |

| LORU02000001.1_Citrobacter_amalonaticus_strain_FDAARGOS_166 | 98. 53 | 91.57 | 94.92 | 98.59 | 82.15 | 81.95 | 81.85 | 81.93 | 98.57 | 98.48 | 98.51 | * | 82.03 | 81. 94 | 98.59 |

| NZ_CP022049.2_Citrobacter_braakii_strain_FDAARGOS_290 | 81. 95 | 82.02 | 82.08 | 82.09 | 92.17 | 92.16 | 92.22 | 90.53 | 81.96 | 81.95 | 81.94 | 82.10 | * | 92. 12 | 81.91 |

| NZ_CP039327.1_Citrobacter_portucalensis_strain_Effluent_1 | 81. 94 | 81.88 | 82.13 | 81.97 | 94.1 | 93.98 | 97.85 | 90.66 | 81.99 | 82.07 | 82.04 | 82.17 | 92.2 | * | 81.98 |

| CP041362.1_Citrobacter_amalonaticus_strain_133355 | 99. 24 | 91.59 | 95.09 | 99.23 | 81.86 | 81.84 | 81.9 | 81.90 | 99.11 | 99.25 | 99.21 | 98.78 | 81.9 | 81. 9 | * |

3.4. digital DNA-DNA hybridization (dDDH) analysis of the strain

dDDH is also another method of determining similarity among bacterial species, by cheaking genome to genome distance. Here in table below the dDDH% value proved that, examined species Citobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 showed highest value in formula 1 which is 99.6% with reference species CP057632.1 and also with the same strain in formula 2 and formula 3 again it showed highest value 95.6% and 97.6 thus, they are more similar among all the reference species showed in resulting table. Further searching formula 1, 2 and 3 we have found that Citobacter sp. HSTU ABK15 with comparing strain CP 022273.1 showed lowest value as 44.2%, 25.3% and 38.1%. Therefore, it is predicted that these two comparing strains showed less similar than another bacterial genome present in Table 3b.

Table 3b. Digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) for species determination of Citrobacter sp. strain HSTU-ABk15.

| Subject strain | dDDH (d0, in %) | C.I. (d0, in %) | dDDH (d4, in %) | C.I. (d4, in %) | dDDH (d6, in %) | C.I. (d6, in %) | G+C content difference (in %) |

| Citrobacter amalonaticus NCTC 10805 | 89.8 | [86.6 -92.4] | 93.5 | [91.7 -95.0] | 92.9 | [90.6 -94.7] | 0.05 |

| Citrobacter telavivensis 6105 | 68.9 | [65.0 -72.6] | 45.7 | [43.2 -48.3] | 65.0 | [61.7 -68.3] | 0.09 |

| Citrobacter farmeri DSM 17655 | 79.9 | [75.9 -83.3] | 44.2 | [41.7 -46.8] | 73.2 | [69.8 -76.4] | 0.02 |

| Citrobacter rodentium NBRC 105723 | 48.7 | [45.2 -52.1] | 28.4 | [26.0 -30.9] | 42.5 | [39.5 -45.5] | 1.27 |

| Citrobacter sedlakii NBRC 105722 | 61.6 | [57.9 -65.2] | 27.8 | [25.5 -30.3] | 51.1 | [48.0 -54.1] | 1.34 |

| Citrobacter diversus NCTC 10849 | 48.4 | [45.0 -51.8] | 27.1 | [24.7 -29.6] | 41.7 | [38.8 -44.8] | 0.21 |

| Citrobacter koseri NCTC10786 | 50.2 | [46.7 -53.6] | 26.8 | [24.4 -29.2] | 42.8 | [39.8 -45.8] | 0.43 |

| Levinea malonatica NCTC 10810 | 49.7 | [46.3 -53.2] | 26.8 | [24.5 -29.3] | 42.5 | [39.6 -45.6] | 0.41 |

| Citrobacter werkmanii NBRC 105721 | 47.8 | [44.4 -51.3] | 25.1 | [22.8 -27.6] | 40.4 | [37.4 -43.4] | 1.3 |

| Citrobacter youngae CCUG 30791 | 46.8 | [43.4 -50.2] | 25.1 | [22.8 -27.6] | 39.7 | [36.7 -42.8] | 1.58 |

| Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 13311 | 37.8 | [34.4 -41.3] | 24.8 | [22.5 -27.2] | 33.4 | [30.5 -36.5] | 1.26 |

| Salmonella typhi NCTC 8385 | 37.0 | [33.6 -40.5] | 24.8 | [22.5 -27.2] | 32.9 | [29.9 -36.0] | 1.29 |

| Salmonella enterica LT2 | 37.2 | [33.9 -40.7] | 24.8 | [22.4 -27.2] | 33.0 | [30.1 -36.1] | 1.14 |

| Salmonella enteritidis ATCC 13076 | 38.2 | [34.9 -41.7] | 24.7 | [22.4 -27.2] | 33.7 | [30.8 -36.8] | 1.24 |

| Salmonella choleraesuis DSM 14846 | 37.3 | [33.9 -40.8] | 24.6 | [22.3 -27.1] | 33.0 | [30.1 -36.1] | 1.24 |

Kosakonia oryzendophytica REICA_082

| 26.8 | [23.4 -30.4] | 21.6 | [19.4 -24.0] | 24.6 | [21.7 -27.7] | 0.35 |

3.5. Whole genome and housekeeping genes phylogenetic tree of the strain

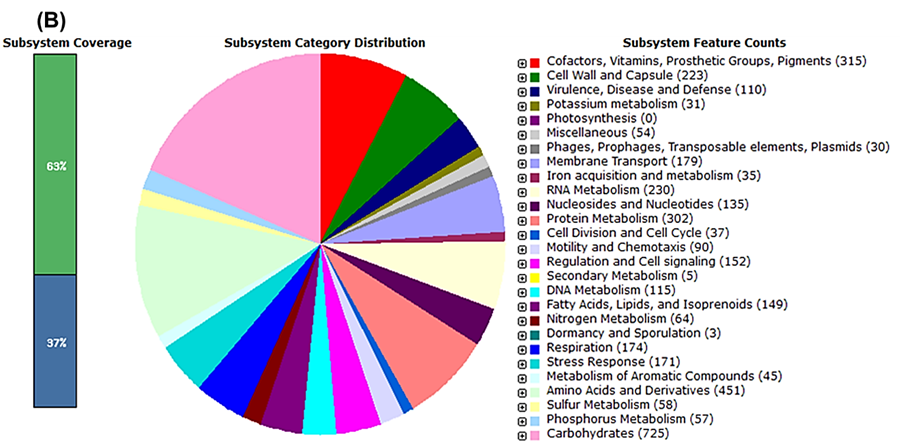

The phylogenetic tree investigation depended on entire genome groupings of identified Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 detaches from rice shoot and with other 30 genome (Figure 2A). Comparison genomes are gathered from NCBI, is a public database Gene Bank. The level of repeat trees in which the related taxa bunched together in the bootstrap test (1000 recreates) is displayed close to the branches. The examined strains Citobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 is showed very similar connection with two groups are – CP 064180.1 Citobacter amalonaticus strain CA 71 and CP 057632.1 Citrobacter sp. RHB –C15, as they construct monophyletic group (Figure 2A). Therefore, it is suggested that Citobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15, CP 064180.1 Citobacter amalonaticus strain CA 71 and CP 057632.1 Citobacter sp. RHB – C15 are derived from same ancestor. The phylogenomic relationship analysis of the housekeeping genes of the strains with their nearest homologs revealed that the recA gene of strain Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 clustered with the recA genes of strains, Citrobacter amalonaticus FDAARGOS165, Citrobacter amalonaticus CA71, and Citrobacter sp. RHB20-C15 with 41% similarity (Figure 2B). Furthermore, the gyrB gene of Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 clustered the gyrB gene of strains Citrobacter amalonaticus FDAARGOS165, Citrobacter amalonaticus FDAARGOS166, and Citrobacter sp. RHB20-C175 demonstrating up to 97% similarity (Figure 2C). Conversely, the gyrB gene of HSTU-ABk15 paired with Citrobacter amalonaticus FDAARGOS122 at a sister node with 77% similarity. The rpoB gene of Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 associated with the rpoB gene of Citrobacter amalonaticus CA71 and Citrobacter sp. RHB20-C15 (Figure 2D). These findings suggested that Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 is most closely related to Citrobacter amalonaticus FDAARGOS166, with notable genetic distances among their nearest homologs in the databases (Figure 2D). The 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis also confirmed the strain were not placed in the same node/cluster and deviated from its nearest homologs (Citrobacterwerkmanii NBRC105721) into a separate cluster (Figure 2E).

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree of the strain Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15. A) Phylogenetic tree made using A) whole genome sequences B) recA geen, C) gyrB gene, D) rpoB gene, E) 16S rRNA gene of the strain Citrobacter sp. HSTU-Bk15.

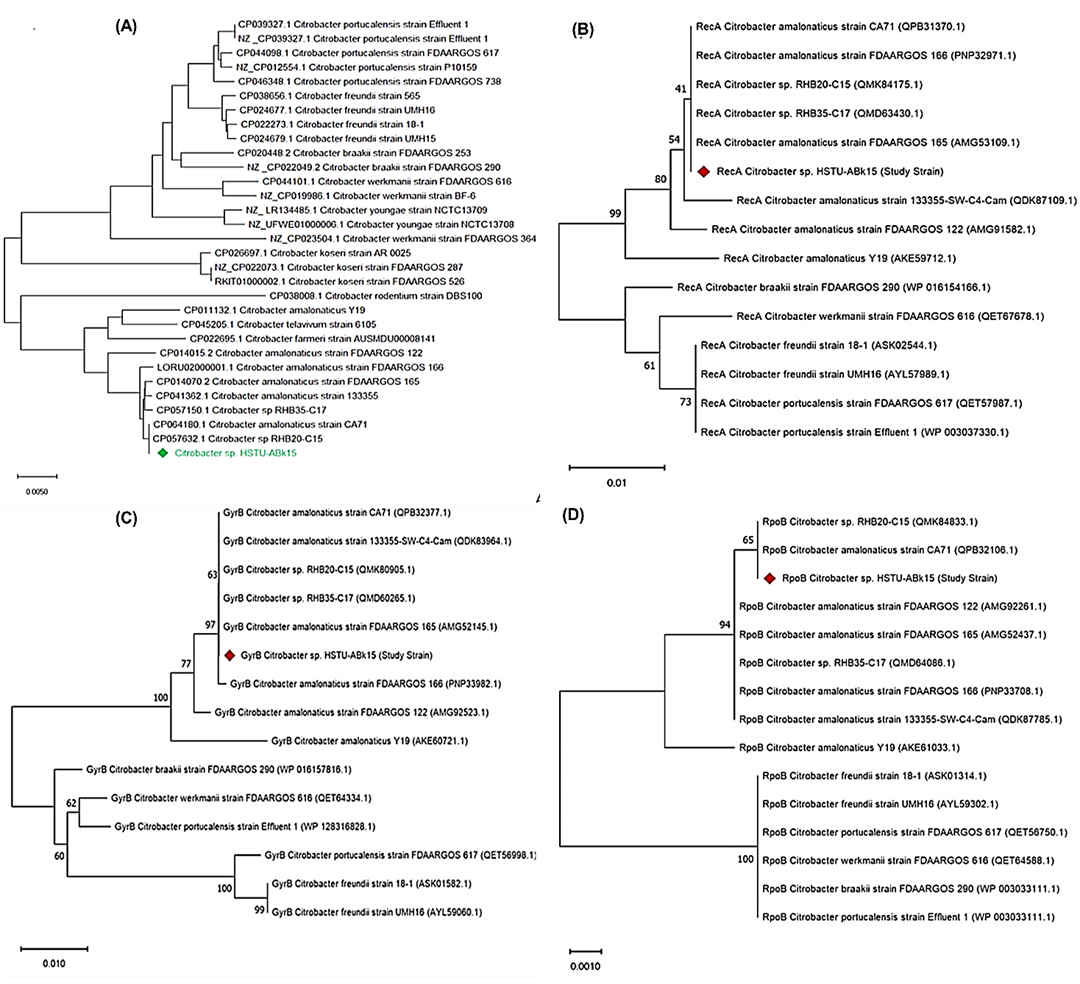

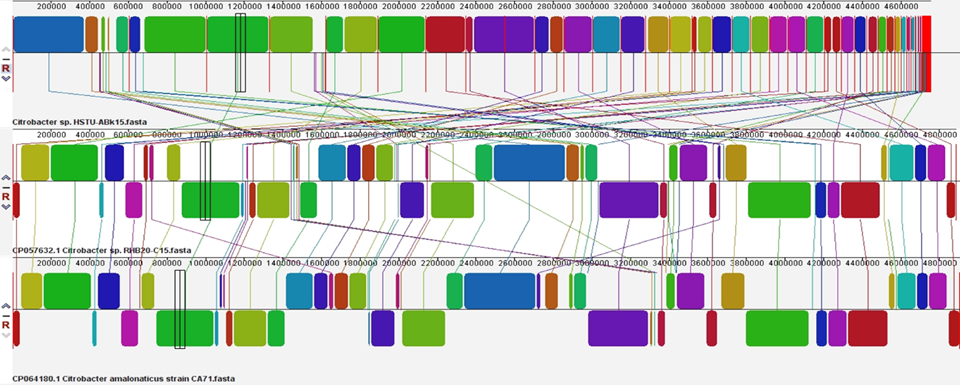

3.6. Progressive mauve

The locally collinear squares (LCB) of the genomes of the three nearest strains, specifically Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15, CP057632.1 Citrobacter sp. RHB 20_C15 and CP064180.1 Citrobacter amalonaticus strain CA71, were surveyed using Progressive Mauve (Figure 3). Indeed, the LCBs in the genome of Citrobacter sp. HSTU ABK 15 are related by lines to similarly tinted LCBs in the genomes of RHB 20_C15, and CA71 strains, independently. The constraints of the LCBs of Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 and various strains taken in assessment are all around considered as breakpoints of genome changes. As shown in Figure, the LCBs of the Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 genome are not really planned with the LCBs of the genomes used for relationship, as shown in Figure. Honestly, a piece of the light blue-tinted LCB of the Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 genome is eradicated, which has displayed in various genomes. So, it recommends that Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15, strain is much differed from its closest strains, which demonstrates its transformative properties.

Figure 3. Circular comparative genome map of Citrobacter species showing whole-genome alignment of the study strain (Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABK15) against reference Citrobacter genomes. From outer to inner rings: annotated CDS on forward and reverse strands, conserved genomic regions among compared genomes, GC content, and GC skew. Genome size is indicated in megabase pairs (Mbp).

3.7. Pangenome analysis

Pangenome analysis process represents entire set of genes from all strains in a legitimate way. The arrangement of the entire genome of Citrobacter sp. HSTU ABK 15 with other close to explicit strains, is Visualized by purple tone (short area) (Figure 4). Right side of Bottom in the diagram is limited the center genome family’s presents within clades of examined and referenced bacterial strains. On other hand, the middle part represents the number of shell genome of these strains. The GC skew is seen in neighborhood genomic districts essentially presented by RNA amalgamation, however the generally genomic extremity because of replication is available no matter what these nearby impacts, and the GC slant is in this way seen in intragenic locales as well as in the third nucleotide positions in codons. Since a couple ori quality and end positions had been distinguished by trial implies, examination of GC slant was first utilized for the computational expectation of ori and ter positions in genome successions.

Figure 4. Progressive Mauve alignment (LCBs) of the strain Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 with their nearest homologs.

3.8. Abundance plant growth promoting genes

In the genome of Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 nitrogen fixation gene (nif JSUL,iscUAR) are annotated (Table 4a). Moreover, nitrosative stress tolerance gene norR,nsrR,glnK etc,nitrogen metabolism regulatory protein glnD, glnB, pstN, Siderophores (fes, entFS, and fepA) are plant hormones, phosphate metabolism, biofilm formation, root colonization, sulfur detection and metabolism, which contribute to the development of plant growth, were identified.Acc deaminase producing gene dcyD, rimM, vital IAA producing gene trpCF, trpABSD, pitA, pstSCAB, phoUAEBR, pnt AB, ppx, ppk1. Additionally, vital genes for producing chemotaxins,motility, adhesive structure, trehalose metabolism in plant are also identify in the experimental genome sequence. Therefore, this study examined almost all aspects of PGP such as nitrogen fixation, IAA, siderophore, phosphate, ACC, HCN, and ammonia production in this study, Citobacter sp. HSTU-ABK 15 isolates showed positive siderophore production. Siderophore production by these species anticipates the importance of plant nutrients in mature ripening conditions in iron-rich conditions. The gene showed the strong activity of siderophore and the biosynthesis method of siderophore (fes, entFS, and fepA) was also observed in its genome study.

Table 4a. Genes associated with PGP traits Citrobacter sp. strain HSTU-ABk15.

| PGP activities description | Gene Name | Gene annotation | Chromosome location | Locus Tag (HSTU | E.C. number |

| Nitrogen fixation | nifJ | Pyruvate: ferredoxin (flavodoxin) oxidoreductase | 89885..93409 | GN159_00425 | - |

| nifE | nitrogenase iron-molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis protein | - | |||

| nifH | nitrogenase iron protein | 1.18.6.1 | |||

| nifA | nif-specific transcriptional activator | - | |||

| nifB | nitrogenase cofactor biosynthesis protein | - | |||

| nifM | nitrogen fixation protein | - | |||

| nifS | cysteine desulfurase | 80147..81361 | GN159_13755 | 2.8.1.7 | |

| nifU | Fe-S cluster assembly protein | - | |||

| nifN | nitrogenase iron-molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis protein | - | |||

| nifT | putative nitrogen fixation protein | - | |||

| nifK | nitrogenase molybdenum-iron protein subunit beta | 1.18.6.1 | |||

| nifV | homocitrate synthase | 2.3.3.14 | |||

| iscU | Fe-S cluster assembly scaffold | 79735..80121 | GN159_13750 | - | |

| iscA | Fe-S cluster assembly protein | 79392..79715 | GN159_13745 | - | |

| iscR | Fe-S cluster assembly transcriptional regulator | 81597..82088 | GN159_13760 | - | |

| nifL | Nitrogen fixation negative regulator | - | |||

| Nitrosative stress | norR | nitric oxide reductase transcriptional regulator | 71118..72635 | GN159_15825 | - |

| nsrR | Nitric oxide sensing transcriptional repressor | 21715..22140 | GN159_20345 | - | |

| ntrB | Nitrate ABC transporter | - | |||

| glnK | P-II family nitrogen regulator | 167620..167958 | GN159_08475 | - | |

| norV | anaerobic nitric oxide reductase flavorubredoxin | 72823..74268 | GN159_20345 | - | |

Nitrogen metabolism regulatory protein | glnD | Bifunctional uridylyl removing protein | 35056..37728 | GN159_04990 | 2.7.7.59 |

| glnB | Nitrogen regulatory protein P-II | 105885..106223 | GN159_13860 | - | |

| ptsN | Nitrogen regulatory protein PtsN | 71533..72024 | - | ||

| Ammonia assimilation | gltB | glutamate synthase large subunit | 59432..63892 | GN159_17450 | 1.4.1.13 |

| gltS | sodium/glutamate symporter | 52826..54031 | GN159_16320 | ||

| amtB | Ammonium transporter AmtB | 166302..167588 | "GN159_08470 | - | |

Nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase and associated transporters | - | nitrate reductase subunit alpha | 222272..226015 | GN159_01070 | 1.7.99.4 |

| narH | nitrate reductase subunit beta | 220740..222275 | GN159_01065 | 1.7.99.4 | |

| narJ | nitrate reductase molybdenum cofactor assembly chaperone | 220033..220743 | GN159_01060 | - | |

| narI | respiratory nitrate reductase subunit gamma | 219356..220033 | GN159_01055 | 1.7.99.4 | |

| NirD | nitrite reductase small subunit NirD | 223444..223770 | GN159_09940 | - | |

| napA | nitrate reductase catalytic subunit NapA | 5160..7646 | GN159_12040 | - | |

| napB | nitrate reductase cytochrome c-type subunit | 9195..9644 | GN159_12055 | 1.9.6.1 | |

| ACC deaminase | dcyD | D-cysteine desulfhydrase | 436619..437605 | GN159_02115 | 4.4.1.15 |

| rimM | ribosome maturation factor RimM | 43700..44248 | GN159_21015 | - | |

| Siderophore | |||||

| Siderophore enterobactin | fes | enterochelin esterase | 20211..21419 | GN159_07885 | 3.1.1.- |

| entF | enterobactin non-ribosomal peptide synthetase EntF | 16069..19965 | GN159_07875 | 6.3.2.14 | |

| entC | isochorismate synthase EntC | 8204..9379 | GN159_07840 | 5.4.4.2 | |

| entS | enterobactin transporter EntS | 10552..11790 | GN159_07850 | - | |

| entE | 2,3-dihydroxybenzoyl)adenylate synthase | 6587..8194 | GN159_07835 | 2.7.7.58 | |

| entD | enterobactin synthase subunit EntD | 23982..24605 | GN159_07895 | 6.3.2.14 | |

| entH | proofreading thioesterase EntH | 4545..4958 | GN159_07820 | 3.1.2.- | |

| fhuA | ferrichrome porin FhuA | 52979..55231 | GN159_05065 | - | |

| fhuB | Fe (3+)-hydroxamate ABC transporter permease FhuB | 49265..51247 | GN159_05050 | - | |

| fhuC | Fe3+-hydroxamate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | 52134..52931 | GN159_05060 | - | |

| fhuD | Fe (3+)-hydroxamate ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 51244..52134 | GN159_05055 | - | |

| fhuF | Siderophore iron reductase | 155146..155934 | GN159_03720 | - | |

| tonB | TonB system transport protein TonB | 196254..196970 | GN159_00930 | - | |

| fepB | Fe2+-enterobactin ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 9564..10502 | GN159_07845 | - | |

| fepG | iron-enterobactin ABC transporter permease | 12903..13895 | 12903..13895 | - | |

| exbD | TonB system transport protein ExbD | 85669..86094 | GN159_17055 | - | |

| - | TonB family protein | - | |||

| - | ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 97798..98715 | GN159_15950 | - | |

| rpoA | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit alpha | 11226..12215 | GN159_21745 | 2.7.7.6 | |

| rpoB | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta | 24571..28599 | GN159_21625 | 2.7.7.6 | |

| exbB | tol-pal system-associated acyl-CoA thioesterase | 84928..85662 | GN159_17050 | - | |

| Plant hormones | |||||

| IAA production | trpCF | bifunctional indole-3-glycerol-phosphate synthase TrpC | 183231..184589 | GN159_00860 | 4.1.1.48/5.3.1.24 |

| trpS | tryptophan--tRNA ligase | 219626..220630 | GN159_09920 | 6.1.1.2 | |

| trpA | tryptophan synthase subunit alpha | 185793..186599 | GN159_00870 | 4.2.1.20 | |

| trpB | tryptophan synthase subunit beta | 184600..185793 | GN159_00865 | 4.2.1.20 | |

| trpD | bifunctional anthranilate synthase glutamate amido transferase component | 181632..183227 | GN159_00855 | 2.4.2.18/4.1.3.27 | |

| Phosphate metabolism | pitA | inorganic phosphate transporter PitA | 92676..94175 | GN159_09340 | - |

| pstS | phosphate ABC transporter substrate-binding protein PstS | 57255..58295 | GN159_20100 | - | |

| pstC | phosphate ABC transporter permease PstC | 56103..57062 | GN159_20095 | - | |

| pstA | phosphate ABC transporter permease PstA | 55213..56103 | GN159_20090 | - | |

| pstB | phosphate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein PstB | 54342..55142 | GN159_20085 | - | |

| phoU | phosphate signaling complex protein PhoU | 53592..54317 | GN159_20080 | 3.5.2.6 | |

| ugpB | sn-glycerol-3-phosphate ABC transporter substrate-binding protein UgpB | 144375..145691

| GN159_09600 | -- | |

| ugpE | sn-glycerol-3-phosphate ABC transporter substrate-binding protein UgpE | 145798..146685 | GN159_09605 | - | |

| phoA | alkaline phosphatase | 255735..257150 | GN159_08885 | 3.1.3.1 | |

| phoE | phosphoporin PhoE | 4235..5287 | GN159_22245 | - | |

| phoB | phosphate response regulator transcription factor PhoB | 243156..243845 | GN159_08820 | - | |

| phoR | phosphate regulon sensor histidine kinase PhoR | 241819..243114 | GN159_08815 | 2.7.13.3 | |

| ppx | exopolyphosphatase | 44189..45730 | GN159_13610 | 3.6.1.11 | |

| ppk1 | polyphosphate kinase 1 | 42118..44184 | GN159_13605 | 2.7.4.1 | |

| phoH | phosphate starvation-inducible protein PhoH | 77077..77985 | GN159_15210 | - | |

| pntA | Re/Si-specific NAD(P)(+) transhydrogenase subunit alpha | 21952..23340 | GN159_06365 | 1.6.1.2 | |

| pntB | Re/Si-specific NAD(P)(+) transhydrogenase subunit beta" | 21952..23340 | GN159_06365 | - | |

| phoQ | two-component system sensor histidine kinase PhoQ | 17911..19374 | GN159_21970 | 2.7.13.3 | |

Biofilm formation

| tomB | Hha toxicity modulator TomB | 156839..157213 | GN159_08395 | - |

| luxS | S-ribosylhomocysteine lyase | 54902..55417 | GN159_15720 | 4.4.1.21 | |

| murJ | Murein biosynthesis integral membrane protein MurJ | 44743..46278 | GN159_15010 | - | |

| flgH | Flagellar basal body L-ring protein FlgH | 37858..38556 | GN159_14960 | - | |

| flgJ | Flagellar assembly peptidoglycan hydrolase FlgJ | 35798..36748 | GN159_14950 | 3.2.1.- | |

| flgK | Flagellar hook-associated protein FlgK | 34098..35732 | GN159_14945 | - | |

| flgL | Flagellar hook-filament junction protein FlgL | 33130..34083 | GN159_14940 | - | |

| flgM | Flagellar biosynthesis anti-sigma factor FlgM | 43934..44227 | GN159_15000 | - | |

| flgA | Flagellar basal body P-ring formation protein | 43184..43840 | GN159_14995 | - | |

| flgB | Flagellar basal body rod protein FlgB | 42611..43027 | GN159_14990 | - | |

| flgC | Flagellar basal body rod protein FlgC | 42203..42607 | GN159_14985 | - | |

| flgI | Flagellar basal body P-ring protein FlgI | 36748..37845 | GN159_14955 | - | |

| flgG | Flagellar basal-body rod protein FlgG | 38614..39396 | GN159_14965 | - | |

| motA | Flagellar motor stator protein MotA | 403908..404801 | GN159_01925 | - | |

| motB | Flagellar motor protein MotB | 402982..403911 | GN159_01920 | - | |

| efp | elongation factor P | 199268..199834 | 199268..199834 | - | |

| hfq | RNA chaperone Hfq | 15692..16000 | GN159_20315 | - | |

Sulfur assimilation and metabolism

| cysZ | sulfate transporter CysZ | 13096..13857 | GN159_21180 | - |

| cysK | cysteine synthase A | 14021..14992 | GN159_21185 | 2.5.1.47 | |

| cysM | cysteine synthase CysM | 21306..22217 | GN159_21230 | 2.5.1.47 | |

| cysA | sulfate/thiosulfate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein CysA | 22327..23421 | GN159_21235 | - | |

| cysW | sulfate/thiosulfate ABC transporter permease CysW" | 23411..24286 | GN159_21240 | - | |

| cysC | adenylyl-sulfate kinase | 113797..114402 | GN159_16040 | 2.7.1.25 | |

| cysN | sulfate adenylyl transferase subunit CysN | 114402..115829 | GN159_16045 | 2.7.7.4 | |

| cysD | sulfate adenylyl transferase subunit CysD | 115839..116747 | GN159_16050 | 2.7.7.4 | |

| cysH | Phosphor adenosine phosphosulfate reductase | 118125..118859 | GN159_16060 | 1.8.4.8 | |

| cysI | assimilatory sulfite reductase (NADPH) | 118918..120630 | GN159_16065 | 1.8.1.2 | |

| cysJ | NADPH-dependent assimilatory sulfite reductase flavoprotein subunit | 120630..122429 | GN159_16070 | 1.8.1.2 | |

| cysT | sulfate/thiosulfate ABC transporter permease CysT | 24286..25119 | GN159_21245 | - | |

| cysE | serine O-acetyltransferase | 96590..97411 | GN159_16540 | 2.3.1.30 | |

| cysQ | 3'(2'),5'-bisphosphate nucleotidase CysQ | 42762..43502 | GN159_20460 | 3.1.3.7 | |

| cysK | cysteine synthase A | 14021..14992 | GN159_21185 | 2.5.1.47 | |

| cysS | cysteine--tRNA ligase | 101698..103083 | GN159_08160 | 6.1.1.16 | |

| fdxH | formate dehydrogenase subunit beta | 66311..67195 | GN159_19720 | - | |

| Antimicrobial peptide | pagP | lipid IV(A) palmitoyltransferase PagP | 19072..19650 | GN159_14155 | 2.3.1.251 |

| sapC | peptide ABC transporter permease SapC | 150822..151712 | GN159_00715 | - | |

| sapB | peptide ABC transporter permease SapB | 149870..150835 | GN159_00710 | - | |

| lipA | lipoyl synthase | 21780..22745 | GN159_14180 | 2.8.1.8 | |

| lipB | lipoyl(octanoyl) transferase LipB | 24206..24847 | GN159_14190 | 2.3.1.181 | |

| amyA | alpha-amylase | GN159_02155 | 444158..445645 | 3.2.1.1 | |

| Synthesis of resistance inducers | |||||

| Methanethiol | metH | methionine synthase | 8358..12041 | GN159_10125 | 2.1.1.13 |

| 2,3-butanediol | ilvB | acetolactate synthase large subunit | 10737..12431 | GN159_19875 | - |

| ilvN | acetolactate synthase small subunit | 10443..10733 | GN159_19870 | 2.2.1.6 | |

| ilvA | Serine, threonine dehydratase | 83915..85459 | GN159_19345 | 4.3.1.19 | |

| ilvC | ketol-acid reductoisomerase | 73955..75430 | GN159_19305 | 1.1.1.86 | |

| ilvY | HTH-type transcriptional activator IlvY | 75589..76491 | GN159_19310 | - | |

| ilvD | Dihydroxy-acid dehydratase | 85462..87312 | GN159_19350 | 4.2.1.9 | |

| ilvM | acetolactate synthase 2 small subunits | 88322..88585 | GN159_19360 | 2.2.1.6 | |

| isoprene | idi | isopentenyl-diphosphate Delta-isomerase | 206722..207270 | GN159_03980 | 5.3.3.2 |

gcpE/ ispG | flavodoxin-dependent (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl-diphosphate synthase | 61021..62139 | GN159_13680 | 1.17.7.1 | |

| ispE | 4-(cytidine 5'-diphospho)-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase | 241790..242641 | GN159_01155 | 2.7.1.148 | |

| Spermidine synthesis | speE | Polyamine aminopropyltransferase | 78192..79058 | GN159_05175 | 2.5.1.16 |

| speA | biosynthetic arginine decarboxylase | 267633..269609 | GN159_06005 | 4.1.1.19 | |

| speB | agmatinase | 266569..267489 | GN159_06000 | 3.5.3.11 | |

| speD | adenosylmethionine decarboxylase | 79074..79868 | GN159_05180 | 4.1.1.50 | |

nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase and associated transporters | - | nitrate reductase subunit alpha | 222272..226015 | GN159_01070 | 1.7.99.4 |

| narH | nitrate reductase subunit beta | 220740..222275 | GN159_01065 | 1.7.99.4 | |

| narJ | nitrate reductase molybdenum cofactor assembly chaperone | 220033..220743 | GN159_01060 | - | |

| narI | respiratory nitrate reductase subunit gamma | 219356..220033 | GN159_01055 | 1.7.99.4 | |

| NirD | nitrite reductase small subunit NirD | 223444..223770 | GN159_09940 | - | |

| napA | nitrate reductase catalytic subunit NapA | 5160..7646 | GN159_12040 | - | |

| napB | nitrate reductase cytochrome c-type subunit | 9195..9644 | GN159_12055 | 1.9.6.1 | |

| Symbiosis-related | gcvR | glycine cleavage system transcriptional repressor | 26311..26949 | GN159_13530 | - |

| pyrC | dihydroorotase | 51561..52607 | GN159_15045 | 3.5.2.3 | |

| gcvT | glycine cleavage system aminomethyltransferase | 188966..190060

| GN159_03895 | 2.1.2.10 | |

| phnC | phosphonate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | 121787..122575 | GN159_10630 | - | |

| tatA | Sec-independent protein translocasesubunit TatA | 12862..13131 | GN159_19015 | - | |

| bacA | undecaprenyl-diphosphate phosphatase | 46469..47290 | GN159_16875 | 3.6.1.27 | |

| zur | Transcriptional repressor /zinc uptake transcriptional repressor | 62145..62660 | GN159_10355 | - | |

| Oxidoreductase | sodB | superoxide dismutase [Fe] | 75750..76331 | GN159_06615 | 1.15.1.1 |

| gpx | glutathione peroxidase | 149085..149636 | GN159_06975 | 1.11.1.9 | |

| osmC | peroxiredoxin OsmC | 59451..59882 | GN159_19680 | 1.11.1.15 | |

| Hydrolase | ribA | GTP cyclohydrolase II | 165668..166258 | GN159_00790 | 3.5.4.25 |

| folE | GTP cyclohydrolase I FolE | 58055..58723 | GN159_12285 | 3.5.4.16 | |

| bglX | beta-glucosidase BglX | 82930..85227 | GN159_12410 | 3.2.1.21 | |

| malZ | maltodextrin glucosidase | 236687..238504 | GN159_08800 | 3.2.1.20 | |

| bglA | 6-phospho-beta-glucosidase | 38561..39991 | GN159_13590 | 3.2.1.86 | |

| - | chitinase | - | |||

| gdhA | NADP-specific glutamate dehydrogenase | 193575..194918 | GN159_07215 | 1.4.1.4 | |

| - | cellulase | 60128..61237 | N159_09220 | 3.2.1.4 | |

| amyA | alpha-amylase | 444158..445645 | GN159_02155 | 3.2.1.1 | |

| Root colonization | |||||

| Chemotaxis | malE | maltose/maltodextrin ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 49812..51002 | GN159_10300 | - |

cheY

| Two-component system response regulator/ chemotaxis protein CheY | 393087..393476 | GN159_01880 | -

| |

| cheB | chemotaxis-specific protein-glutamate methyltransferase CheB | 393494..394543 | GN159_01885 | 3.1.1.61 | |

| mcp | methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein | 136006..137670 | GN159_03625 | ||

| tap | methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein IV | 395426..397027 | GN159_01895 | - | |

| cheW | chemotaxis protein CheW | 400422..400925 | GN159_01910 | - | |

| cheA | chemotaxis protein CheA | 400947..402977 | GN159_01915 | - | |

| rbsB | ribose ABC transporter substrate-binding protein RbsB | 83115..84005 | GN159_20215 | - | |

Motility Flagellar components | flhA | flagellar biosynthesis protein FlhA | 383641..385719 | GN159_01845 | - |

| flhB | flagellar type III secretion system protein | 385712..386866 | GN159_01850 | - | |

| flhC | Transcriptional activator FlhC/ flagellar transcriptional regulator | 404927..405505 | GN159_01930 | - | |

| flhD | flagellar transcriptional regulator FlhD | 405508..405858 | GN159_01935 | - | |

| fliZ | flagella biosynthesis regulatory protein FliZ | 438602..439153 | GN159_02125 | - | |

| fliD | Flagellar filament capping protein FliD | 441889..443295 | GN159_02140 | - | |

| fliS | flagellar export chaperone Proein | 443311..443718 | GN159_02145 | - | |

| fliE | flagellar hook-basal body complex protein FliE | 457283..457597 | GN159_02235 | - | |

| fliF | flagellar basal body M-ring protein FliF | 457814..459508 | GN159_02240 | - | |

| fliG | flagellar motor switch protein FliG | 459501..460499 | GN159_02245 | - | |

| fliT | flagella biosynthesis regulatory protein FliT | 443718..444089 | GN159_02150 | ||

| fliH | flagellar assembly protein FliH | 460492..461196 | GN159_02250 | - | |

| fliL | flagellar basal body-associated protein FliL | 464344..464808 | GN159_02270 | - | |

| fliM | flagellar motor switch protein FliM | 464813..465817 | GN159_02275 | - | |

fliP

| Flagellar biosynthetic protein FliP/flagellar type III secretion system pore protein | 466604..467341 | GN159_02290 | - | |

| fliQ | flagellar biosynthesis protein FliQ | 467351..467620 | GN159_02295 | - | |

| flgK | flagellar hook-associated protein FlgK | 323454..325103 | GPJ58_01465 | - | |

| fliD | flagellar filament capping protein FliD | 345803..347203 | GPJ58_01580 | - | |

| Adhesive structure | hofC | protein transport protein HofC | 106592..107794 | GN159_05290 | - |

| Adhesin production | PgaA | poly-beta-1,6 N-acetyl-D-glucosamine export porin PgaA | - | ||

| pgaB | poly-beta-1,6-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine N-deacetylase PgaB | 3.5.1.- | |||

| pgaC | poly-beta-1,6 N-acetyl-D-glucosamine synthase | - | |||

| pgaD | poly-beta-1,6-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine biosynthesis protein | - | |||

| Superoxide dismutase | sodA | superoxide dismutase [Mn] | 83355..83975 | GN159_18020 | 1.15.1.1 |

| sodB | superoxide dismutase [Fe] | 75750..76331 | GN159_06615 | 1.15.1.1 | |

| sodC | superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] SodC2 | 64324..64845 | GN159_06565 | 1.15.1.1 | |

| Trehalose metabolism | treB | PTS trehalose transporter subunit IIBC | 16145..17563 | GN159_03075 | 2.7.1.201 |

| treC | alpha,alpha-phosphotrehalase | 14439..16097 | GN159_03070 | 3.2.1.93 | |

| treR | HTH-type transcriptional regulator TreR | 17709..18656 | GN159_03080 | ||

| otsA | alpha,alpha-trehalose-phosphate synthase | 407099..408520 | GN159_01945 | 2.4.1.15 | |

| otsB | trehalose-phosphatase | 408495..409295 | GN159_01950 | 3.1.3.12 | |

| lamB | maltoporin LamB | 52556..53881 | GN159_10310 | - |

3.9. Abundance of abiotic stress tolerance genes

Interestingly, we found stress tolerance gene such as cspA, cspD, cspE (for cold shock), heat shock proteins- smpB, hslR, groES, rpoS, (absobingly here we found two class of chaperone protein one group of heat shock chaperone- ibpA, ibpB, hspQ and another group of molecular chaperone–dnaJ, dnaK,djl A), proteins responsible for arsenic tolerance – arsA, arsB, ars C, arsD, arsR, arsH in the genome of Citobacter sp. HSTU-ABK 15. Interestingly, the gene associated with drought stress tolerance includes proA, proB,proQ , proX found within the genome of Citobacter sp. HSTU-ABk 15. These genes were linked to the modification of drought-induced functions. In addition, genes of copper homeostasis and magnesium copA, copE and copC, copD, cusR, cusF, cusA were found in the genome of Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 (Table 4b).

Table 4b. Gene associated with stress tolerating Citrobacter sp. strain HSTU-ABK15.

| Activity description | Gene Name | Gene annotation | Chromosome location (HSTU-ABk15) | Locus Tag (HSTU-ABk15) | E.C. number |

| Cold Shock protein | cspA | RNA chaperone/antiterminator CspA | 24474..24686 | GN159_09060 | - |

| cspE | transcription antiterminator/RNA stability regulator CspE | 19824..20033

| GN159_14160 | - | |

| cspD | cold shock-like protein CspD | 146770..146991 | GN159_13405 | - | |

| Heat Shock protein | smpB | SsrA-binding protein SmpB | 34197..34679 | GN159_20960 | - |

| hslR | ribosome-associated heat shock protein Hsp15 | 203743..204144 | GN159_09840 | ||

| ibpA | heat shock chaperone IbpA | 25153..25566 | GN159_19945 | - | |

| ibpB | heat shock chaperone IbpB | 24576..25004 | GN159_19940 | - | |

| hspQ | heat shock protein HspQ | 94338..94655 | GN159_18475 | - | |

| groL | chaperonin GroEL | 194845..196491 | GN159_10970 | - | |

| groES | Heat shock protein 60 family co-chaperone GroES | 194508..194801 | GN159_10965 | - | |

| yegD | Putative heat shock protein YegD | 120266..121618 | GN159_12565 | ||

| dnaJ | molecular chaperone DnaJ | 216138..217271 | GN159_05775 | - | |

| dnaK | molecular chaperone DnaK | 217357..219273 | GN159_05780 | - | |

| djlA | co-chaperone DjlA | 163982..164797 | GN159_05535 | ||

| rpoH | RNA polymerase sigma factor RpoH | 134729..135583 | GN159_09555 | - | |

| lepA | elongation factor 4 | 130011..131810 | GN159_13965 | 3.6.5.n1 | |

| grpE | nucleotide exchange factor GrpE | 38863..39456 | GN159_20990 | - | |

| Heavy metal resistance | |||||

| Arsenic tolerance | arsA | arsenical pump-driving ATPase | 239306..241057 | GN159_04105 | - |

| arsB | arsenical efflux pump membrane protein ArsB | 241105..242394

| GN159_04110 | - | |

| arsC | arsenate reductase (glutaredoxin) | 242407..242832 | GN159_04115 | 1.20.4.1 | |

| arsD | arsenite efflux transporter metallochaperone ArsD | 238926..239288

| GN159_04100 | ||

| arsR | metalloregulator ArsR/SmtB family transcription factor | 238525..238878 | GN159_04095 | - | |

| arsH | Arsenical reseistance protein arsH | - | |||

| acrR | ultidrug efflux transporter transcriptional repressor AcrR | 151167..151820 | GN159_08380 | - | |

| acrA | Multidrug efflux RND transporter periplasmic adaptor subunit | 151962..153155 | GN159_08385 | - | |

| acrD | Multidrug efflux RND transporter permease | 14279..17392 | GN159_13475 | - | |

| trkA | Trk system potassium transporter TrkA | 7689..9065 | GN159_21715 | - | |

| Chromium resistance | chrA | Chromate efflux transporter | - | ||

| Magnesium transport | corA | magnesium/cobalt transporter CorA | 31974..32924 | GN159_19105 | - |

| corC | CNNM family magnesium/cobalt transport protein CorC | 45543..46421 | GN159_14295 | - | |

| cobA | uroporphyrinogen-III C-methyltransferase | 221113..222486 | GN159_09930 | 2.1.1.107 | |

| Copper homeostasis | copA | copper-exporting P-type ATPase CopA | 127025..129526 | GN159_08285 | - |

| copC | copper homeostasis periplasmic binding protein CopC | - | |||

| copD | copper homeostasis membrane protein CopD | 347230..348102 | GN159_01660 | - | |

| cutC | copper homeostasis protein CutC | 376921..377667 | GN159_01815 | ||

| cusR | copper response regulator transcription factor CusR | 84118..84801 | GN159_08105 | ||

| cusA | CusA/CzcA family heavy metal efflux RND | 77741..80887 | GN159_08085 | - | |

| cusF | cation efflux system protein CusF | 82194..82538 | GN159_08095 | - | |

| Zinc homeostasis | znuA | zinc ABC transporter substrate-binding protein ZnuA | 364902..365846 | GN159_01745 | - |

| znuB | zinc ABC transporter permease subunit ZnuB | 366677..367462

| GN159_01755 | - | |

| znuC | zinc ABC transporter ATP-binding protein ZnuC | 365925..366680 | GN159_01750 | - | |

| Zinc, cadmium, lead, mercury homeostasis | zntA | Zn(II)/Cd(II)/Pb(II) translocating P-type ATPase ZntA | 126783..128981 | GN159_09515 | - |

| Zinc homeostasis | adhP | alcohol dehydrogenase AdhP | 95847..97039 | GN159_00445 | 1.1.1.1 |

| htpX | protease HtpX | 335203..336084 | GN159_01605 | 3.4.24.- | |

| zntB | zinc transporter ZntB | 105499..106482 | GN159_00490 | - | |

| Manganese homeostasis | mntR | manganese-binding transcriptional regulator MntR | 76576..77049

| GN159_13085 | - |

| mntP | manganese efflux pump MntP | 327375..327941 | GN159_01555 | - | |

| mntH | Mn (2+) uptake NRAMP transporter MntH | 7071..8309 | GN159_11090 | - | |

| zinc/cadmium/mercury/lead-transporting ATPase | 3.6.3.3 | ||||

| Drought resistance | nhaA | Na+/H+ antiporter NhaA | 209625..210791 | GN159_05750 | - |

| chaA | sodium-potassium/proton antiporter ChaA | 234512..235612 | GN159_01115 | - | |

| chaB | putative cation transport regulator ChaB | 234008..234238 | GN159_01110 | - | |

| proA | glutamate-5-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | 6690..7943 | GN159_22255 | 1.2.1.41 | |

| proB | glutamate 5-kinase | 5575..6678 | GN159_22250 | 2.7.2.11 | |

| proQ | RNA chaperone ProQ | 338345..339031 | GN159_01615 | - | |

| proV | glycine betaine/L-proline ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | 43418..44620

| GN159_15665 | - | |

| proW | glycine betaine/L-proline ABC transporterpermease ProW | 44613..45677

| GN159_15670 | - | |

| proX | glycine betaine/L-proline ABC transporter substrate-binding protein ProX | 45746..46741

| GN159_15675 | - | |

| proP | glycine betaine/L-proline transporter ProP | 129061..130563 | GN159_10660 | - | |

| proS | proline--tRNA ligase | 4928..6646 | GN159_04850 | 6.1.1.15 | |

| betA | choline dehydrogenase | 39978..41654 | GN159_07965 | 1.1.99.1 | |

| betB | betaine-aldehyde dehydrogenase | 38492..39964 | GN159_07960 | 1.2.1.8 | |

| betT | choline BCCT transporter BetT | - | |||

| trkA | Trk system potassium transporter TrkA | 7689..9065 | GN159_21715 | - | |

| trkH | Trk system potassium transporter TrkH | 654..2105 | GN159_18960 | - | |

| kdbD | two-component system sensor histidine kinase KdbD | 79412..82099 | GN159_14470 | 2.7.13.3 | |

| kdpA | potassium-transporting ATPase subunit KdpA | 84741..86420 | GN159_14485 | - | |

| kdpB | potassium-transporting ATPase subunit KdpB | 82673..84721 | GN159_14480 | - | |

| kdpC | potassium-transporting ATPase subunit KdpC | 82089..82664 | GN159_14475 | - | |

| kdpE | /two-component system response regulator KdpE | 78738..79415 | GN159_14465 | - | |

| kdpF | two-component system response regulator KdpE | 86420..86509 | GN159_14490 | - |

3.10. Genes associated with pesticide degradation

Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 has identified a genetic component that includes the destruction of organophosphorus pesticides. In the genome of HSTU-ABk15 a total number of 22 enzymes were found which are involved in pesticide degrading, where six enzymes are categorized as phosphonate C-P lyase system protein (phn GHIJKL), two genes categorized as cyclic family protein specified in gene annotation in the table no. as cyclic-guanylate-specific phosphodiesterase (pdeH), cyclic di-GMP phosphodiesterase(pdeR). Moreover, in the HSTU-ABk15 genome 1,6-anhydro-N-acetylmuramyl-L-alanineamidase, anaerobic glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase subunit, glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase subunit, Glycerol phosphodiester phosphodiesterase, leucyl aminopeptidase were also observed. In this study, Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 22 different genes that product was suggested to be involved in damaging organophosphorus pesticides (Table 4c).

Table 4c. Genes associated with pesticide degradation available in the genome of Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15.

| Activity description | Gene Name | Gene annotation | Chromosome location (HSTU-ABk15) | Locus Tag (HSTU-ABk15) | E.C. number |

| ampD | 1,6-anhydro-N-acetylmuramyl-L-alanineamidase | 103013..103576 | GN159_05270 | 3.5.1.28 | |

| glpA | anaerobic glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase subunit | 159935..161563 | GN159_11860 | 1.1.5.3 | |

| glpB | glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase subunit | 158686..159945 | GN159_11855 | 1.1.5.3 | |

| glpQ | Glycerol phosphodiester phosphodiesterase | 163200..164276 | GN159_11870 | 3.1.4.46 | |

| Pesticide degrading | pepA | leucyl aminopeptidase | 47850..49361 | GN159_03220 | 3.4.11.1 |

| pepB | aminopeptidase PepB | 75048..76331 | GN159_13720 | 3.4.11.23 | |

| pepD | cytosol nonspecific dipeptidase | 142..1599 | GN159_22225 | 3.4.13.18 | |

| pepE | -/dipeptidase PepE | 14030..14719 | GN159_10135 | 3.4.13.21 | |

| phnF | phosphonate metabolism transcriptional regulator PhnF | 118999..119724 | GN159_10615 | - | |

| phnD | phosphonate ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 120622..121638 | GN159_10625 | - | |

| phnG | phosphonate C-P lyase system protein PhnG | 118546..118998 | GN159_10610 | - | |

| phnH | phosphonate C-P lyase system protein PhnH | 117965..118549 | GN159_10605 | 2.7.8.37 | |

| phnI | phosphonate C-P lyase system protein PhnI | 116898..117965 | GN159_10600 | - | |

| phnJ | phosphonate C-P lyase system protein PhnJ | 116060..116908 | GN159_10595 | - | |

| phnK | phosphonate C-P lyase system protein PhnK | 115305..116063 | GN159_10590 | - | |

| phnL | phosphonate C-P lyase system protein PhnL | 114546..115232 | GN159_10585 | - | |

| phnM | lpha-D-ribose 1-methylphosphonate 5 triphosphatediphosphatase | 113413..114549 | GN159_10580 | 3.6.1.63 | |

| phnP | phosphonate metabolism protein PhnP | 111630..112388 | GN159_10565 | 3.1.4.55 | |

| phnO | aminoalkylphosphonate N-acetyltransferase | 112435..112869 | GN159_10570 | 2.3.1.- | |

| pdeH | cyclic-guanylate-specific phosphodiesterase | 71233..72000 | GN159_09250 | - | |

| - | carboxylesterase family protein | 53879..55387 | GN159_00275 | - | |

| pdeR | cyclic di-GMP phosphodiesterase | 158035..160026 | GN159_00745 | 3.1.4.52 |

3.11. Modeling and validation of pesticide-degrading protein models in Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15

3.11.1. Characterization of Pesticide-Degrading Protein Models in Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15

Total twenty-five model proteins related to pesticide-degradation in Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 were identified and characterized (Table 5). The model proteins belonged to several enzymes including amidohydrolases, Glp, Pep, Phn alongside AmpD, carboxylesterase, PdeH, and PdeR. The model proteins based on their best hit with PDB disclosed varied secondary structural composition with α-helix, β–strand, η-coil, and disordered regions. In consequence, a substantial number of models proteins established high quality as ERRAT scores was found directly above 85% for AmpD, GlpA, PepA, PepB, PepE, PhnF, PhnG, PhnH, PhnK, PhnL, and PhnO proteins. Likewise, VERIFY (3D-ID) score were remarkably high for PepA (99.80%), PepE (99.13%), GlpQ (97.49%), and PhnP (98.02%) proteins. In addition, PepA, PdeH, PepB, PepD, and PepE had placed residues 84.2%, 80.9%, 82.3%, 80.1%, 81.5% in the core region of Ramachandran plot. To strengthen the interpretation of the docking analysis, the quality and reliability of all modeled proteins were systematically evaluated using multiple complementary structural validation parameters prior to docking. These parameters directly indicate whether the predicted protein structures are suitable for ligand–protein interaction studies and whether the observed docking outcomes can be interpreted with confidence. The TM-score, RMSD, sequence identity, and coverage collectively demonstrate the structural reliability of the modeled proteins. Most proteins showed high TM-scores (>0.85) withlow RMSD values (<2.0 Å), indicating strong structural similarity to experimentally solved PDB templates. For example, AmpD, PepA, PepD, PepE, and PhnJ exhibited TM-scores ≥0.95 with RMSD values below 0.5 Å, reflecting highly accurate backbone conformations. Such structural fidelity ensures that predicted active-site geometry is preserved during docking simulations, thereby enhancing confidence in ligand binding poses and interaction energies. In contrast, proteins such as PhnD showed a markedly low TM-score (0.37) and high RMSD (8.04 Å), suggesting reduced structural confidence; docking results for these proteins were therefore interpreted cautiously. The proportion of α-helices, β-strands, coils, and disordered regions provides insight into structural stability and flexibility, both of which influence ligand binding. Most enzymes displayed balanced secondary structure distributions with low disordered regions (≤5%), supporting the formation of well-defined binding pockets. Proteins with higher coil or disordered content (e.g., PhnD and PdeH) may exhibit greater conformational flexibility, potentially affecting docking precision and binding energy variability. ERRAT quality scores for most proteins exceeded 85%, and VERIFY-3D scores were generally above 80%, confirming favorable non-bonded atomic interactions and proper residue–environment compatibility. High ERRAT (e.g., PdeH: 97.97; PhnO: 99.25) and VERIFY-3D scores (e.g., PepA: 99.80; PepE: 99.13) indicate structurally sound models, supporting the biological relevance of docking-derived interactions. Lower scores (e.g., GlpB and PhnD) suggest potential local structural inaccuracies, which were considered when evaluating docking affinity rankings. Ramachandran statistics further validated stereochemical correctness. Most models exhibited >75–85% residues in the most favored (core) regions with minimal residues in disallowed regions (<2%), indicating proper backbone geometry. Proteins such as PepA, PhnG, and Amidohydrolase showed excellent conformational stability, strengthening the reliability of predicted ligand interactions within their active sites. Taken together, these parameters demonstrate that the majority of proteins used for docking possess high structural accuracy, correct stereochemistry, and stable secondary structures, which are prerequisites for meaningful docking analysis. Consequently, docking interactions observed for high-quality models (e.g., AmpD, Pep family proteins, PhnJ–PhnP) reliably reflect biologically plausible binding modes. Conversely, docking results for proteins with comparatively lower validation scores were interpreted qualitatively rather than quantitatively.

Table 5. Protein modeling and validation of pesticides degrading model proteins.

| Model protein | Best PDB Hit | TM score, RMSD,Iden,cov | -helix, -strand -coll,disordered | ERRAT (quality score) | VERIFY (3D-ID score) % | Ramchandran plot (core, allow, gener, disallow) % |

| AmpD | 1l2s | 0.99,0.48,0.83,1.0 | 22,14,63,4 | 90.44 | 90.37 | 64.2,28.9,3.8,3.1 |

| carboxylesterase | 5x61 | 0.95,1.26,0.29,0.97 | 32,13,53,2 | 85.56 | 91.24 | 72.6,21.4,4.3,1.7 |

| GlpA | 2rgo | 0.88,2.17,0.22,0.93 | 36,19,43,3 | 91.01 | 78.04 | 70.3,22.1,5.1,2.5 |

| GlpB | 1lpf | 0.76,1.56,0.15,0.79 | 27,19,53,1 | 41.84 | 69.45 | 70.3,22.1,3.6,3.9 |

| GlpQ | 1ydy | 0.91,0.37,0.89,0.91 | 29,14,56,8 | 85.42 | 97.49 | 74.9,18.5,5.3,1.3 |

| PdeH | 5m3c | 0.93,1.50,0.23,0.98 | 40,19,40,7 | 97.97 | 63.53 | 80.9,14.8,2.2,2.2 |

| PdeR | 5xgb | 0.81,0.68,0.26,0.81 | 42,22,34,1 | 54.04 | 76.47 | 80.8,12.8,3.6,2.8 |

| PepA | 1gyt | 0.99,0.26,0.97,1.0 | 33,20,45,1 | 92.88 | 99.80 | 84.2,14.0,1.2,0.7 |

| PepB | 6cxd | 0.96,0.34,0.76,0.97 | 33,19,47,0 | 95.46 | 94.38 | 82.3,15.3,1.3,1.1 |

| PepD | 3mru | 0.99,0.28,0.63,1.0 | 28,25,46,2 | 92.24 | 97.32 | 80.1,16.7,1.7,1.4 |

| PepE | 1fye | 0.95,0.29,0.85,0.96 | 26,26,47,1 | 95.00 | 99.13 | 81.5,14.3,4.2,0.0 |

| PhnD | 3vkg | 0.37,8.04,0.05,0.63 | 47,17,35,8 | 66.15 | 59.32 | 50.0,33.9,11.3,4.8 |

| PhnF | 2wvo | 0.98,0.52,0.19,0.98 | 29,32,38,4 | 94.37 | 86.72 | 76.6,19.3,2.8,1.4 |

| PhnG | 4xb6 | 0.92,1.21,0.68,0.96 | 45,25,29,5 | 97.10 | 72.67 | 87.4,9.6,1.5,1.5 |

| PhnH | 2fsu | 0.85,0.71,0.83,0.86 | 26,21,52,6 | 96.23 | 87.63 | 73.8,22.6,1.8,1.8 |

| PhnI | 4xb6 | 0.97,1.19,0.87,0.99 | 38,12,48,5 | 89.34 | 46.20 | 81.6,15.2,1.6,1.6 |

| PhnJ | 4xb6 | 0.98,0.24,0.95,0.98 | 23,19,57,3 | 90.10 | 83.69 | 79.3,14.9,4.1,1.7 |

| PhnK | 4fwi | 0.97,0.84,0.31,0.98 | 37,23,39,3 | 91.39 | 91.27 | 82.4,14.4,1.9,1.4 |

| PhnL | 5nik | 0.92,1.18,0.27,0.96 | 33,26,39,1 | 92.27 | 96.63 | 73.8,19.8,4.5,2.0 |

| PhnM | 2oof | 0.92,1.67,0.15,0.96 | 33,21,45,0 | 81.02 | 64.81 | 66.1,25.3,5.4,3.3 |

| PhnO | 5f46 | 0.91,1.42,0.18,0.99 | 34,31,34,2 | 99.25 | 86.11 | 73.6,17.1,5.4,3.9 |

| PhnP | 3g1p | 0.98,0.38,0.80,0.99 | 11,28,59,0 | 87.96 | 98.02 | 72.5,22.2,3.4,1.9 |

Amidohyrolase (9962…10732) | 2E11 | 0.96,0.34,0.76,0.97 | 22,33,43,1 | 76.61 | 84.38 | 87.1,12.1,0.4,0.4 |

Amidohyrolase Family protein (232305…234173) | 3IGH | 0.95,1.26,0.29,0.97 | 30,16,52,1 | 68.71 | 82.85 | 86.7,10.8,1.4,1.1 |

Amidohyrolase (6225..7358) | 20GJ | 0.76,1.56,0.15,0.79 | 27,23,49,2 | 69.12 | 85.03 | 83.7,13.2,1.2,1.8 |

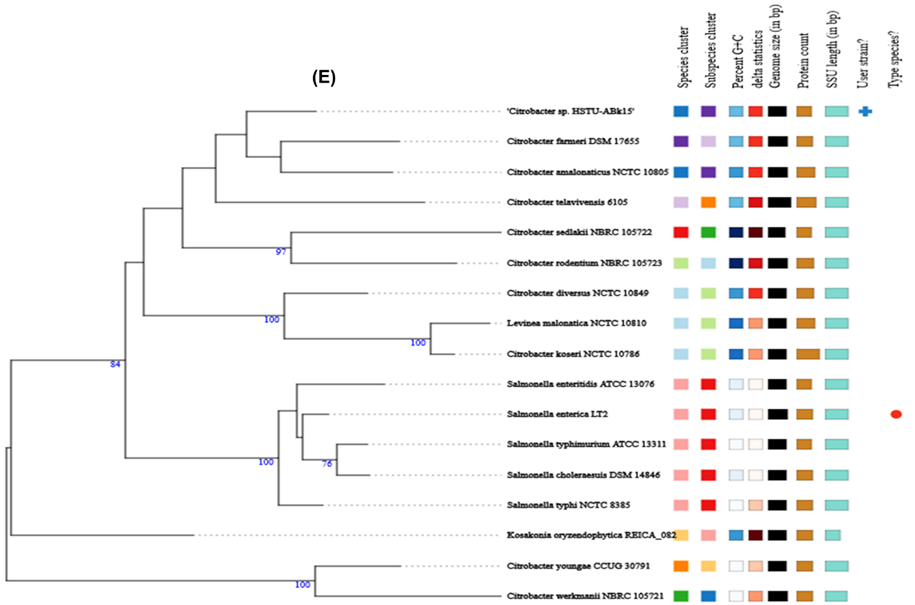

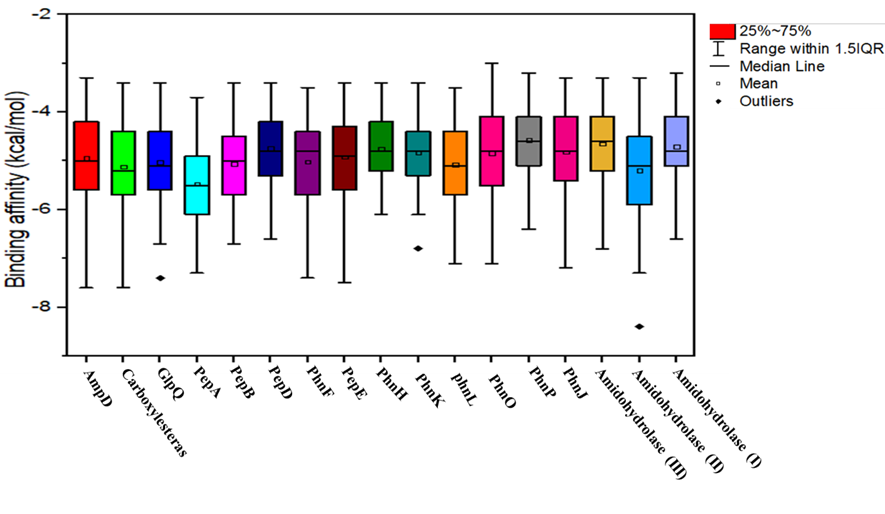

3.11.2. Virtual screening and box plot of model protein and pesticide complex

The virtual screening of the selected 17 model proteins of HSTU-ABK15 with 99 different pesticides, shown binding score ranges from -9 Kcal/mol to -3 Kcal/mol (Figure 5). It is shown that most of the binding scores are occupied between the 1st and 3rd quartile in the box plot (Figure 5), where the lower and upper quartile designates the 1st and 3rd quartile scores. Interestingly, total three model proteins (GlpA, PhnK, amidohydrolase II) of Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15, were placed outlier data points. The virtual screening results also showed that the binding affinity of many pesticide ligands crossed over to -6.5~8.0 Kcal/mol for organophosphate degrading potential proteins AmpD, GlpQ, PepA, PepB, PepD, PepE, PhnF, PhnK, PhnL, PhnO, PhnP, and the amidohydrolase models proteins from Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABK15.

Figure 5. Graphical representation of virtual screening results of pesticide-degrading validated top scorer model proteins among 105 different organophosphorus pesticides and other common pesticides applied in farmers’ fields.

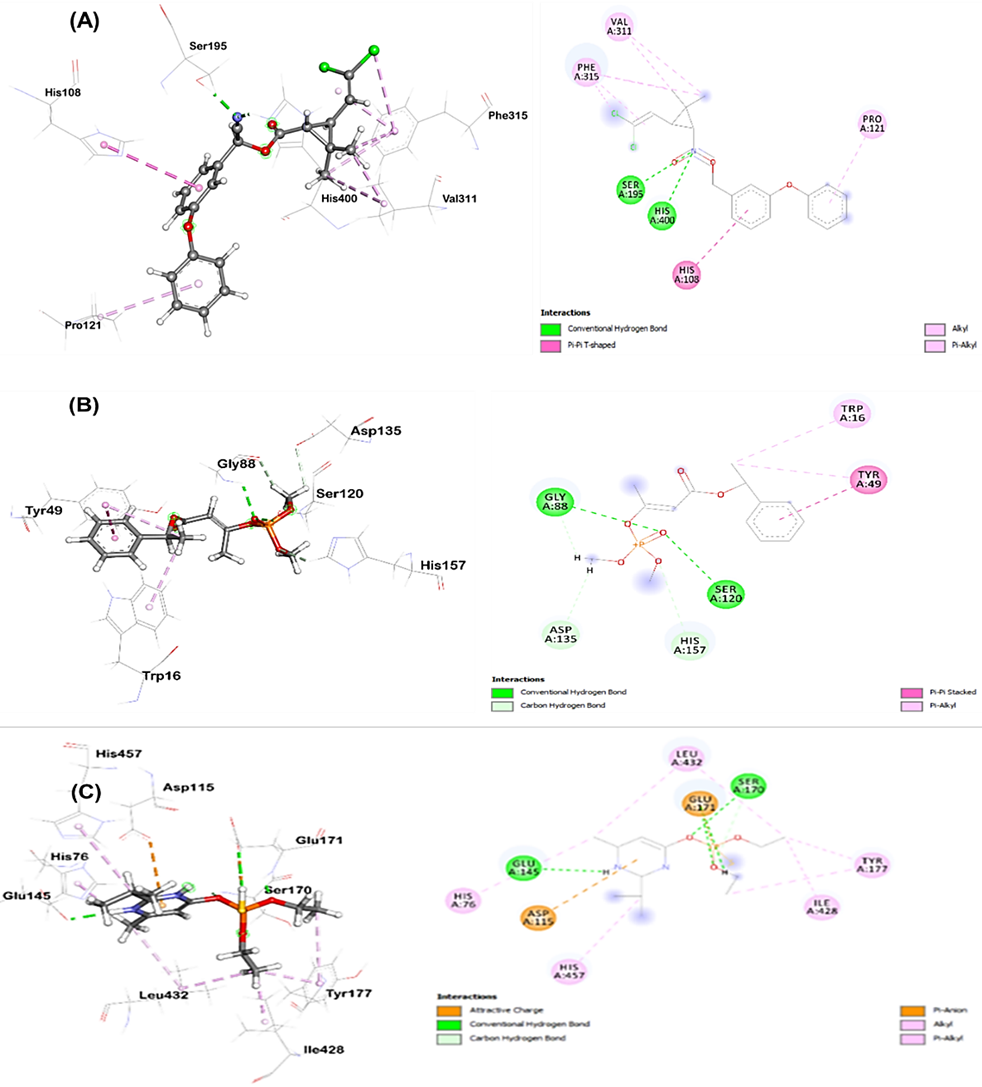

3.11. 3. Docking and interactions of selected proteins of Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABK15

Moreover, carboxylesterase protein-cypermethrin docked complex demonstrated the interaction with multiple residues. In particular, conventional H-bonds were made by the Ser195, His400 to the O-atom of cypermethrin compound. Besides, a great number of residues were interacted with the ligand molecule by alkyl, pi-alkyl, and pi-pi T-shaped bonds namely, Phe315, Val311, Pro121 and His108 sequentially (Figure 6A). As seen in Figure 6B, the PepD is greatly interacted with diazinon through multiple amino acid residues. In fact, the O-atom in phosphodiester bond of diazinon is attacked by Ser170 via conventional H-bond. The Leu432, His76, His457Glu171, Tyr177 and Ile428 was provided alkyl, π-alkyl, π-anion, π-sulfur and carbon hydrogen bonds interaction with diazinon compound respectively. The Glu145 is providing conventional H-bond with N-H-atom of diazinon compound and Asp115 attached with the ligand by attractive charge. Astonishingly, the PepD of Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 formed potential catalytic triad in the binding pocket region with residue Ser170-His457-Asp115. The interaction distances among the residues of catalytic site were recorded within <5.25 Å. These multiple interactions account for the good binding affinity of diazinon with pepD. Furthermore, PepE anchored with crotoxyphos compound revealed a great interaction (Figure 6C). Such as, Ser120 and Gly88 interacted with O atom of crotoxyphos molecule by conventional hydrogen bond. Besides, pi-alkyl, pi-pi-T shaped and carbon hydrogen bonds were made by Asp135, His157, Trp16, Tyr49 with crotoxyphos compound respectively.

Figure 6. Catalytic triad’s visualization of the complexes, A) carboxylesterase protein-cypermethrin, B) PepD protein-Diazinon, C) PepEprotein-Crotoxyphos.

4. DISCUSSION

The isolation of the multifunctional endophytic bacteria Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 from rice plants reveals a multiuse microbial consortium with broad ecological and biotechnological potential. These strains simultaneously harbored plant growth promotion, degrade the organophosphate pesticide chlorpyrifos, and exhibit antimicrobial biosynthetic potential, underscoring their capacity to address agricultural and environmental challenges through a unified biological framework [7, 21-23]. Distinct enzymatic profiles revealed adaptive metabolic versatility essential for endophytic colonization. Hydrolytic enzymes such as xylanase, amylase, protease, and CMCase suggest efficient host tissue penetration and nutrient [24-27]. Whole-genome sequencing confirmed close relationships to C. amalonaticus, supported by high ANI and dDDH values [28-29]. Functional annotation identified genes linked to nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, ACC deaminase activity, and organophosphate degradation, reflecting a genomic architecture optimized for mutualistic and degradative functions [7,23,30]. These synergistic mechanisms affirm their potential as biofertilizers that could reduce chemical inputs while maintaining crop productivity under environmental constraints [21, 23, 31]. A pivotal finding of this study is the remarkable capacity of these endophytes for pesticides degradation insilico confirmation, offering a crucial eco-friendly solution for mitigating pesticide contamination and a significant step towards sustainable environmental management [7,18,32]. This multifaceted functionality highlights their promise for broader applications in bioremediation and sustainable agriculture [23]. Whole-genome sequencing confirmed close relationships to C. amalonaticus, supported by high ANI and dDDH values [28-29]. Although average nucleotide identity (ANI) and digital DNA-DNA hybridization (dDDH) values confirmed that the isolate belongs to Citrobacter amalonaticus, comparative genomic analysis revealed strain-specific genetic features associated with endophytic colonization, xenobiotic degradation, and plant growth–promoting functions. Therefore, the novelty of the isolate is defined at the strain level rather than at the species level. Functional annotation identified genes linked to nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, ACC deaminase activity, and organophosphate degradation, reflecting a genomic architecture optimized for mutualistic and degradative functions [23, 30]. These synergistic mechanisms affirm their potential as biofertilizers that could reduce chemical inputs while maintaining crop productivity under environmental constraints [21, 23, 31]. A pivotal finding of this study is the remarkable capacity of these endophytes for pesticides degradation insilico confirmation, offering a crucial eco-friendly solution for mitigating pesticide contamination and a significant step towards sustainable environmental management [18, 32-33]. This multifaceted functionality highlights their promise for broader applications in bioremediation and sustainable agriculture [23].

Further molecular investigation unequivocally revealed the intricate enzymatic machinery facilitating this bioremediation, providing critical insights into its efficiency and specificity. Comprehensive characterization and quality validation of numerous pesticide-degrading model proteins from all three strains further corroborated their functional integrity, revealing high structural integrity, as evidenced by favorable ERRAT and VERIFY-3D scores, and optimal residue placement in Ramachandran plots. Reliable docking analysis depends critically on the structural accuracy and stereochemical quality of protein models [34]. Homology models were generated using templates from PDB and NCBI BLAST, with quality assessed via ProSA-web z-score and Ramachandran plot analysis using PROCHECK [34]. Secondary structure analysis revealed proportions of α-helices, β-strands, turns, and coils [35-36]. Model quality assessment confirmed robustness, with VERIFY3D scores indicating compatibility of 3D atomic models with 1D amino acid sequences when >80% of residues score ≥0.2, and ERRAT scores evaluating non-bonded interactions where values >85-95% reflect high quality [37-40]. Ramachandran plot analysis evaluated stereochemical validity, with residues in core regions indicating good quality [34, 40]. Phn family members, such as those encoded by phnE and phnM, are involved in phosphonate transport and utilization [29]. Docking results for proteins in pesticide degradation pathways were interpreted with caution for models showing structural limitations [41]. Overall, integrated validation parameters using these tools confirm model quality suitable for docking in organophosphate degradation contexts [34,40,42]. Specifically, the models exhibited high percentages of residues in favored Ramachandran regions, typically exceeding 90%, and minimal outliers, ensuring reliable binding site geometries for ligand interactions [43].

Crucially, virtual screening against 99 different pesticides unearthed high binding affinities for numerous proteins with various organophosphate ligands, decisively pointing towards a remarkable broad-spectrum degradation potential. Molecular docking studies precisely elucidated the specific binding interactions at an atomic level: Ser195 and His400 in Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15's carboxylesterase formed conventional H-bonds with cypermethrin; a potential catalytic triad in PepD interacted with diazinon via conventional H-bonds and other residues (Figure 6). These detailed molecular-level insights profoundly validate the observed degradation efficiencies and establish a comprehensive mechanistic framework for understanding the sophisticated endophyte-mediated xenobiotic detoxification processes. The established broad-spectrum degradation potential of these endophytes also suggests their applicability beyond chlorpyrifos to other organophosphorus pesticides, such as those found to be bioremediated by other bacterial species and earthworm associations [23]. The docking results suggest a strong potential for interaction between chlorpyrifos and several predicted enzymes, supporting their putative role in pesticide transformation. Although molecular docking and virtual screening provide valuable insights into enzyme–pesticide interactions, these approaches remain predictive in nature.

In conclusion, the endophytic bacterial strains, Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15, isolated from rice, represent a powerful beneficial microorganism. Their demonstrated genetic repertoire in annotated genome having potentialities in effectively promoting rice plants growth, mediating comprehensive chlorpyrifos bioremediation through well-characterized enzymatic pathways, and exhibiting broad-spectrum antipathogenic activities, position them as highly promising candidates for sustainable biotechnological applications. The study primarily focuses on characterizing the endophytes and their potential beneficial traits, but it does not explicitly detail the molecular mechanisms within the rice plant itself that are influenced by these interactions. Future studies involving targeted enzymatic assays and analytical quantification of chlorpyrifos degradation products will be essential to experimentally validate the predicted degradation mechanisms. Subsequent research should prioritize the isolation, structural elucidation, and functional characterization of the resulting metabolites and associated enzymes to clarify their precise mechanisms of action and ecological interactions, thereby fully harnessing their potential for advancing sustainable agriculture and pharmaceutical innovation which is not substitute for molecular dynamics simulations or experimental validation, which will be addressed in further studies for sustainable green agriculture.

This work was supported by a research project grants by the Institute of research and Training (IRT)-Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University, Dinajpur 5200. This study addresses about 10% AI-assisted text following the journal policy.

This research was supported by the grants from the Institute of Research and Training (IRT)-Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University (HSTU) in fiscal year 2021-2022 at Dinajpur, Bangladesh.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This study did not involve any experiments on human participants or animals; therefore, formal written informed consent was not required by the Institutional Review Board. All figures in this study were created; therefore, no permission for reuse is required for any figure presented herein.

The assembled and annotated genome sequence was deposited in the NCBI and provided accession number Citrobacter sp. HSTU-ABk15 (rice plant shoot) (Accession number: WQMR00000000; BioSample: SAMN13439369; BioProject: PRJNA592761)

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

.

You are free to share and adapt this material for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit.